An East German medical school dedicated to internationalism

Table of contents

I. Without medical sovereignty, there can be no social progress

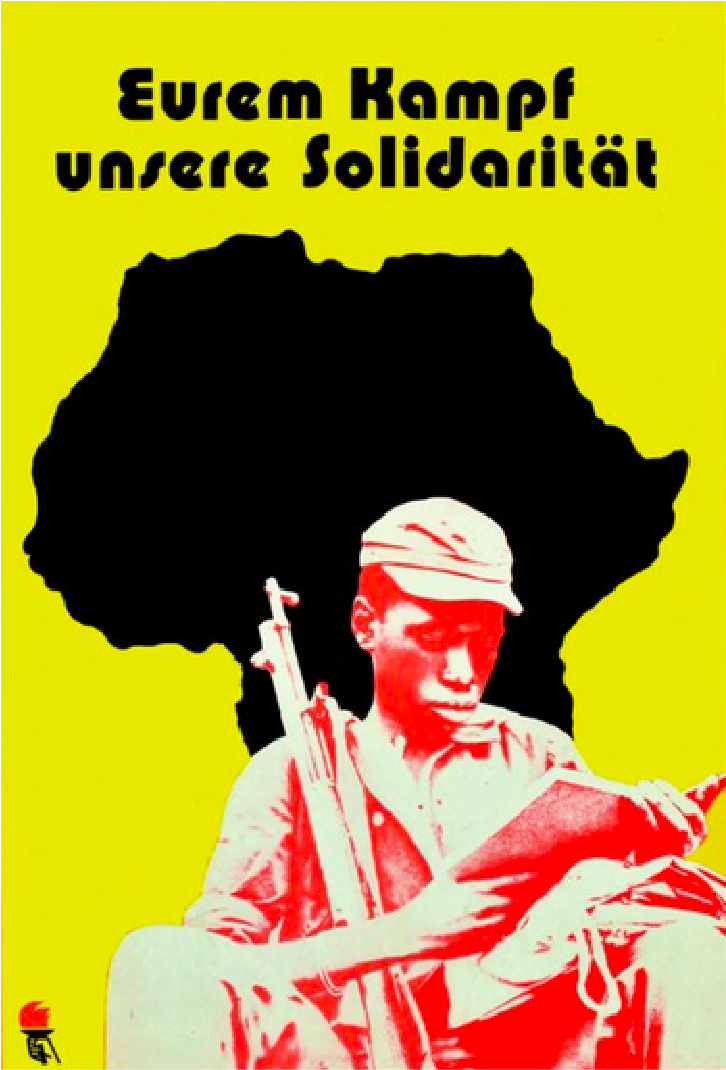

A young man sits with a gun across his shoulder, engrossed in a book. Behind him is a silhouette of the African continent. In 1978, the graphic artist Lola Gruner designed this poster and captioned it with the slogan: “Your struggle, our solidarity”. It strikingly depicts the two fronts of the struggle for independence: armed resistance for the right to self-determination and one’s own dignity; and emancipation from the illiteracy imposed by colonial underdevelopment. Control over education was an instrument through which the colonial system was perpetuated. In the words of Samora Machel, the leader of Mozambique’s national liberation struggle, the colonial educational institutions were “true schools of uprooting”. They suppressed the cultural identity of the people, encouraged a political affinity with the “mother country”, and recruited personnel from among the indigenous population to work as auxiliaries in the colonial administration. The withdrawal of colonial personnel following successful independence struggles then tore massive gaps in the infrastructure of these countries. The young states were now faced with the task of reconstructing society through their own efforts. The former colonizers turned to new methods for preserving economic dependencies and securing spheres of influence, but the national liberation movements found allies in the socialist world.

The emergence of the socialist camp after the Second World War meant that support for the liberation movements could reach new dimensions. The solidarity of the socialist states was guided the principle of delegation: through extensive education initiatives, young students from the newly liberated states acquired the skills and equipment required for the construction of national infrastructure back home. The training of those who had hitherto been systematically denied educational opportunities thus had a fundamentally different character in the socialist states. The focus lay not primarily on the fulfilment of individual life plans or the realisation of a career; the objective was to bring an entire society out of the educational deprivation that had been imposed by the colonial powers.

From 1951 to 1989, between 64,000 and 78,000 students from over 125 countries completed a degree at an academic institution in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, commonly referred to as East Germany).1Damian Mac Con Uladh: „Studium bei Freunden? Ausländische Studierende in der DDR bis 1970“, in: Christian Th. Müller und Patrice G. Poutrus (Hrsg.): Ankunft – Alltag – Ausreise. Migration und interkulturelle Begegnung in der DDR-Gesellschaft. Böhlau / Köln, 2005, S. 175. The number of foreign students is likely much higher if one includes those who came to the GDR for a professional traineeship or semester programme. East Germany was one port amongst many others: Throughout the socialist states, young people from throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America studied a variety of fields at different institutions. The socialist camp thus guaranteed hitherto unattainable educational opportunities.

The GDR, which developed one of the most powerful economies amongst the socialist states, was a key player in this internationalist endeavour. Despite limited resources, East Germany set up training facilities and academic institutions, paid scholarships to international students, and supported trainees in their home countries by, for example, sending brigades of teachers or constructing educational centres. Medical personnel were also dispatched to hospitals and clinics around the world to administer care and provide medical support in deprived or war-torn areas.

Solidarity in the medical field was a decisive moment of proletarian internationalism: where basic medical care is lacking, there can be no social progress. Health infrastructure that guarantees equal access to care is essential for the construction of a democratic society. This thus became an urgent task in the former colonies, and liberation movements, newly independent states, and non-aligned countries turned to the socialist camp for assistance. The GDR’s solidarity consisted of creating structures for self-help. In the short term, this meant limiting direct imperialist dependency mechanisms by supplying medicines and equipment. In the long term, it meant counteracting the “brain drain”, the exodus of medical personnel from the young states by training students who would be able to return home and construct their own health care systems.

A brief look at the situation in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, commonly referred to as West Germany) shows the qualitative difference of the socialist approach: Unlike most capitalist states, West Germany did not charge foreign students tuition fees. The additional costs of studying, however, were not covered by the social benefits system. Foreign students were entitled neither to state assistance for students nor to the social programmes offered to FRG citizens. Before beginning a degree in West Germany, foreign students had to provide proof that they could finance their studies themselves. Such conditions made studying in the FRG impossible for the working classes of the Global South. Furthermore, Western countries have a long tradition of poaching skilled workers from less-developed states in order to compensate for their own shortages of medical personnel. In 1979, while the socialist camp was developing numerous programmes to train medical personnel from the Global South, 90 per cent of all the world’s migrating doctors settled in just five countries: Australia, Canada, the FRG, Great Britain and the USA.2C. R. Hooper: “Adding Insult to Injury: The Healthcare Brain Drain”, in: Journal of Medical Ethics, Vol. 34, Nr. 9 (2008), S. 684–7. This trend has only intensified since the collapse of the socialist world system: since the year 2000, the proportion of foreign-trained doctors in the FRG has risen by more than 270 percent.3From 3,7 % to 13,7 % in the year 2020. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Health Workforce Migration: Migration of doctors, % of foreign trained doctors, letzter Zugriff am 20.04.2023.

In the GDR, on the other hand, foreign students not only received sufficient scholarships to finance their living expenses but were also directly integrated into the GDR’s health and social system, which guaranteed them free medical care. Such measures made it possible for the “damned of the earth” to take up an education. The composition of the student bodies in the two German states vividly demonstrates this fact: In West Germany during the early 1980s, about 50 percent of all international students came from developing countries,4Wolfgang Schmidt-Streckenbach: „Strukturen des Ausländerstudiums in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland“, in: Hans F. Illy und Wolfgang Schmidt-Streckenbach (Hrsg.): Studenten aus der Dritten Welt in beiden deutschen Staaten. Berlin, 1987, S. 51. of which just 6 per cent from Africa;5“The proportion of Black Africans is astonishingly low. The 40 states included here are able to fill just 6% of the study places made available to students from the Third World in the Federal Republic of Germany with their nationals, i.e. around 2,000 persons.” Cf. ibid. during the same period in the East German workers’ and peasants’ state, almost a quarter of all international students came from Africa.6“The GDR’s strong orientation towards individual African states and liberation movements on this continent has led to an increase of a good 6 points for Africa, so that today already around a quarter of all foreign students in the GDR (…) come from this region.” Cf. Roland Wiedmann: “Strukturen des Ausländerstudiums in der DDR”, in: Roland Wiedmann: „Strukturen des Ausländerstudiums in der DDR“, in: Hans F. Illy und Wolfgang Schmidt-Streckenbach (Hrsg.): Studenten aus der Dritten Welt in beiden deutschen Staaten. Berlin, 1987, S. 98. Non-Europeans made up more than two-thirds of the international student body in the GDR.7Cf. ibid., S. 91. The initiative to study was organized through joint agreements between states or political organizations, not by the decisions of individual students. In this way, education was tailored to the respective needs of the liberated states, and the training programmes were embedded in their planning processes as well as those of the GDR. The socialist camp thus practised the exact opposite of the West’s brain drain.

How did this cooperation between the socialist states and the liberation movements come about? What role did solidarity in the medical field play within the framework of the GDR’s wider anti-imperialist strategy? To what extent did those involved in the realisation of such initiatives understand their activity as a contribution to proletarian internationalism?

We posed these questions to Achim Reichardt, the last director of the Solidarity Committee, in a conversation in 2021. He spoke of a variety of examples – from the construction of hospitals in Nicaragua and Vietnam, to cooperation in research and development, to sending medical brigades and shipping supplies across the world. Yet he also informed us of a medical school in the East German town of Quedlinburg and told us that this is where we would have to start. He put us in touch with a former instructor at the school and, with his help, we followed a path that took us to Mali, Lebanon, and Guinea-Bissau. It became clear that this medical school not only represented a neglected side of the GDR’s history8A first more detailed study can be found in: Young-sun Hong: “Know your Body and Build Socialism”. In: Cold War Germany, the Third World, and the Global Humanitarian Regime, 2015, S. 177 – 214., but also a compact example in which the objective and character of the GDR’s medical internationalism could be examined. In the following article, we summarize our research into the school and trace out its role in the GDR’s internationalist and anti-imperialist efforts.

II. The “Medifa” – the GDR’s medical school for international students

During our research, we explored the town of Quedlinburg, unearthed old class books in dark cellars, interviewed former teachers whose stories had previously gone unheard, spoke with town inhabitants, and established regular contact with graduates of the school in various countries. The fact that we succeeded in doing so is primarily due to the close relationships that formed between former teachers and students at the school. The everyday experiences these individuals shared with us can convey a subjective impression of their time in the GDR, and they will be documented in the “Friendship!” Archive. In interviews with former students, we repeatedly encountered the conviction that the medical school in Quedlinburg was an important part of the socialist states’ solidarity, without which “thousands of young people (…) from countries all over the world would not have had access to higher education”.9Anonymized (Palestinian doctor who studied at MediFa in the late 1980s through the PLO), in a written interview with the authors. 28 August 2021. For instructors like Ulrich Kolbe, the school was a deeply humanistic and political institution that embodied the spirit of proletarian internationalism and helped to establish humane conditions in the most exploited and oppressed countries.10Ulrich Kolbe (German instructor at MediFa in the late 1980s), in conversation with the authors. 6 July 2021. Quedlinburg. By examining the school in Quedlinburg as one internationalist institution amongst many across the socialist camp, we sought to also draw out the general nature of socialist solidarity in the educational field. As part of this research, we relied on secondary literature and archival material such as state agreements, party communications and the seminar books that we discovered from the 1980s.

The medical school in Quedlinburg — a small, medieval town in the north of the Harz Mountains — officially bore the name of the first German woman to receive the title of “Doctor of Medicine” in the 18th century: Dorothea Christiane Erxleben. Referred to simply as the “Medifa” by its students and teachers, the school was one of more than 60 medical colleges in the GDR. It had existed as a nurses’ school since 1907 and was converted into a vocational college in 1961. A first class of international trainees was admitted in 1960, and they continued to study alongside East German students until the mid-1960s, when the school began to specialize exclusively in the training of medical personnel from newly independent states or national liberation movements from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The primary professions taught at the Medifa were nursing, medical educators, assistants, physiotherapists, midwives, and orthopaedic mechanics.

The GDR had already been training medical students from the Global South since the early 1950s. These students studied at various technical colleges and universities throughout East Germany. The Medifa became centrally embedded in this infrastructure and was continuously improved in order to meet the special requirements of the international trainees. As a “training centre for foreign citizens”, the school in Quedlinburg, for example, offered subject-specific German lessons, which were attended by those who went on to one of the GDR’s specialist centres.

Medifa students came from Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Mali, Tanzania, Laos, Egypt, the People’s Republic of Yemen, Madagascar, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Palestine, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Laos, Cambodia, and many other countries. For the approximately 2,000 international students who graduated from the school, the financing of their education was part of comprehensive trade or cultural agreements between the GDR and other states. 11The number of students as well as the countries and organisations sending them could be determined from the information provided by the last director of Medifa, Fritz Kolbe, and the supplementary evaluations of the seminar group books from the 1980s by IF DDR. Fritz Kolbe: „Kaderausbildung – Ausdruck des proletarischen Internationalismus“, in: Solidaritätskomitee der DDR (Hrsg.): Für antiimperialistische Solidarität, Ausgabe 37/1984, S. 39. Agreements below the state level were also concluded between various mass organisations in the GDR (e.g., trade unions or the Solidarity Committee) and political or social organisations in the Global South. Many students came at a time when their movements were still fighting for independence. For some former colonies, the Medifa trained their first native medical personnel.

The GDR typically provided the infrastructure for the foreign students, while the partner country was responsible for covering the travel costs – although this could be arranged differently in individual cases. After their arrival, students received scholarships to cover any additional costs of studying. This started at 300 Deutsche Marks, which was above the value of the scholarships that GDR citizens received and could be increased further depending on the students’ qualifications and performance. Those from exiled liberation movements received additional allowances to account for the often-meager funds of their organisations.12Approximately 100 Marks from these scholarships had to be spent on room and board. A 1966 state order laid down the standard procedure for funding stipend payments to foreign citizens training in the medical professions. A higher stipend for certain students was justified on the grounds that the “citizens have been delegated to the GDR by the liberation organisations of countries which are themselves in emigration in Africa. They receive no support from there and consequently have to meet personal needs themselves.” Vgl. BArch DQ 1/3956, „Anordnung über die Finanzierung der beruflichen Aus- oder Weiterbildung von Bürgern aus Entwicklungsländern in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik vom 13.12.1966“.

The first international students to train in Quedlinburg in the early 1960s were 20 young Malian, most of whom successfully graduated as medical assistants. The training of Malian nurses followed shortly thereafter. In 1967, the GDR and Mali drew up a comprehensive agreement on cooperation in the medical field, in which the financing of this training and qualifications for doctors played a central role.13BArch DQ 1/23938, „Abkommen zwischen der Regierung der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik und der Regierung der Republik Mali über die Zusammenarbeit auf dem Gebiet des Gesundheitswesens“, 1967. GDR representatives made their goals clear in an internal report evaluating the planned agreement:

“The realisation of these measures would contribute significantly to deepening the relations between the GDR and the Republic of Mali and to further increasing the reputation of the GDR in Africa. Furthermore, these measures would be an effective contribution to supporting the Malian government’s struggle against imperialist and neo-colonialist attempts at interference.“14BArch DQ 1/23938, „Begründung“, undatiert.

This kind of report reflects the analysis of the socialist camp at the time, according to which the world revolutionary process consisted of three inter-dependent currents: the national liberation struggles in the colonies, the workers’ movements in the capitalist states, and the consolidation of the socialist states. Objectives such as “increasing the reputation of the GDR in Africa” and “supporting the Malian government’s struggle” were thus not contradictory goals. Moreover, agreements like this one between the GDR and Mali were more than a mere quid pro quo: the self-declared intention of the GDR and the world communist movement was to coordinate and strengthen the three currents of the world revolutionary process. Such agreements were understood as important instruments in this endeavor.15In the linked article on Mali’s non-capitalist path and the international communist movement in the 1960s, we elaborate on this point.

III. Learning from one another – internationalism under construction

In a farewell speech, the first Malian students emphasized that there was as yet no experience with such training programmes; medical internationalism was still in its infancy and had to be developed through praxis. The curricula would have to be adapted to the needs of the individual countries – a process that would require mutual learning.

Prior to the training of new student delegations, GDR doctors were typically sent to the corresponding countries to gain an understanding of the conditions and challenges on the ground. The objective was to establish exchanges between local and East German experts while also formulating plans for the immediate supply of pharmaceuticals or supplies. At the same time, doctors and health workers from the partner countries were given the opportunity to visit East Germany at the GDR’s expense and see how the socialist health care system operated.

In order to address the urgent need for medically personnel in the Global South, the GDR reintroduced the profession of physician’s assistant, for it provided students with the skills to administer appropriate care in a relatively short period of time. In an interview for Radio Berlin International in 1989, the then director of the school, Fritz Kolbe, described the significance of this profession:

“The first training objective for nurses in the GDR is that they are reliable assistants for the doctor. In African countries, when the nearest doctor is several hundred kilometers away or no doctor is available at all, this presents nurses with a serious problem. For this reason, we reintroduced an old profession for foreign students: that of the physician’s assistant. This is a profession that lies somewhere between a nurse and a doctor. In the third year of training, our young friends learn the necessary practical skills by working directly alongside a doctor so that they will be able to independently diagnose patients and provide therapy.“16Rundfunk-Beitrag auf Radio Berlin International vom 4. November 1989; vgl. Heinz Odermann: Wellen mit tausend Klängen – Geschichten rund um den Erdball in Sendungen des Auslandsrundfunks der DDR Radio Berlin International. Berlin, 2003, S. 88.

To account for the specific needs of the partner countries, Medifa students were incorporated into the process for developing their own curricula. In 1964, for example, a solution was sought to a problem raised by Nigerian students: in their country, midwifery was one of the competencies of nurses, so training nursing without acquiring the skills of midwifery would mean learning only half a profession by their standards. The Medifa thereafter integrated the two professions into one programme. Over time and in exchange with the partner countries, the Medifa’s curricula were thus improved and expanded to adapt to the specific conditions in the students’ home countries.

From 1965, the Medifa operated as an “educational institution for foreign citizens” and thus specialised exclusively in international students: “We believe that the time has come to end the period of improvisation in the education of foreigners and to give our school a firm structure as an educational institution for foreign citizens.“17BArch DQ 1/6480, Brief von Hildegard Haas, stellvertretende Direktorin der Medizinischen Fachschule Quedlinburg an das Ministerium für Gesundheitswesen, Sektor mittlere medizinische Berufe vom 15.06.1964. This step was linked to the establishment of a separate German teaching department at the school. Previously, many medical students had to attend the Central School for Foreign Citizens in Radebeul, Saxony to learn German. From 1967 onwards, all foreign medical trainees learned German at the Medifa, where high-level courses were offered to prospective medical specialists so that they could learn the specific terminology of their field.

In 1974, the Medifa was also elevated to the rank of a Fachschule (a specialised college). The programmes now consisted of specialist studies and the training period was extended by one year. This corresponded with developments in the GDR’s wider health care system, where nurses and nursing staff received general medical training at a higher academic level.18In the radio report already mentioned, Friedrich Kolbe described what the curriculum of the trainee nurses was like in 1989: “The training lasts just under four years. The first 10 months are reserved exclusively for studying the German language. Then, for two years, four weeks of theory are alternated with four weeks of practice in the nearby district hospital. The first year of training for the future nurses is determined exclusively by practice.” Heinz Odermann: Wellen mit tausend Klängen. Berlin, 2003, p. 88. One year later, the subject of medical pedagogy was also introduced to enable students to act as multipliers by passing on the knowledge they acquired at the Medifa in their home countries. An inventory report from 1979 shows the diversity of the fields of study:

“To support the development of national health services, the GDR has so far concluded health agreements or plans for cooperation in the cultural-scientific field with more than 30 developing countries. Citizens from more than 20 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America receive medical education and further training at universities and technical colleges as well as at health care institutions in our Republic. Numerous cadres from countries of these continents are trained in our state, mainly as nurses, physiotherapists, medical educators, midwives and orthopaedic mechanics. Already trained nurses and laboratory technicians from young national states are qualified in special fields such as microbiology, haematology, anaesthesia, dialysis or in surgical techniques.” 19Neues Deutschland vom 05.01.1979, Seite 2: Pläne für die Zusammenarbeit mit den Entwicklungsländern.

The state planning of all institutions in the GDR’s educational system also meant that cooperation between different medical institutions could be promoted and coordinated. For example, cooperation was established between the Medifa and the Tropical Institute at the Karl Marx University in Leipzig to enable “students to work with applicable knowledge under the conditions of their home countries”, as to Fritz Kolbe said in 1982.2075 Jahre Kreiskrankenhaus Quedlinburg, 1982, S. 66. Particularly in the field of tropical medicine, the Medifa was unable to provide much practical expertise in its early years. This was changed in the 1980s:

“The new department, where dispensary care for tropical travelers is administered, has become a special area in the training of medical students. This includes, among other things, lectures on tropical medicine and internships for foreign students in their third to fifth year of study. Within the framework of a cooperation agreement with the “Dorothea Christiane Erxleben” Medical School in Quedlinburg, the department has been helping to train students from tropical developing countries in nursing since February 1980.”21Neues Deutschland vom 19.05.1980, S. 3: Neue Fachstation für Tropenmedizin.

Cooperation in researching and treating tropical diseases helped both sides. While the African states gained access to research results, the GDR could also draw on local expertise with medicinal plants for its own development of pharmaceuticals. Since the West’s sanctions had severely hindered the GDR’s participation in international research and development initiatives, such cooperation was particularly significant for scientific advancements in East Germany.

The development of the Medifa reflects a learning process in which the specific requirements of the newly liberated states were identified and tailored to. This was not an easy task and required constant communication at multiple levels. Yet, the almost 30-year development of the school exhibits a gradual and continuous refinement of its curricula. By the end of the 1980s, students from almost 50 countries were studying at the Medifa and the school’s capacity had reached its limits. Over the course of the 1980s, some individual self-paying students were also admitted to the school without a scholarship, further speaking to the renown of the GDR’s educational programmes.

IV. Lived solidarity

The Medifa’s core internationalist purpose was to train students for future responsibilities in their home countries; their stay in the GDR was limited by nature. Yet diverse relationships grew out of everyday life at the Medifa. The fact that these connections were often developed organically by those involved in and around the school reflects a basic characteristic of the GDR, namely, that educational institutions were not isolated but closely linked to other areas of society. The Medifa students found themselves in a society in which solidarity with their political organisations was both anchored in the wider populace and upheld by the state. Salam, who came from Lebanon to Quedlinburg in the 1980s, recalled his first impression of East Germany:

I came to the GDR on 11 May 1983 with Interflug [the GDR’s airline]. There were three festivals at that time: May Day, Karl Marx’s birthday, and Liberation Day [from fascism, 8 May]. Berlin was red! I was thrilled. Wherever you looked, everything was red. It was a beautiful and impressive sight for me.“22Salam Abou Mjahed (Lebanese journalist who studied German at the MediFa in the late 1980s), in discussion with the authors. 20 January 2023. Berlin.

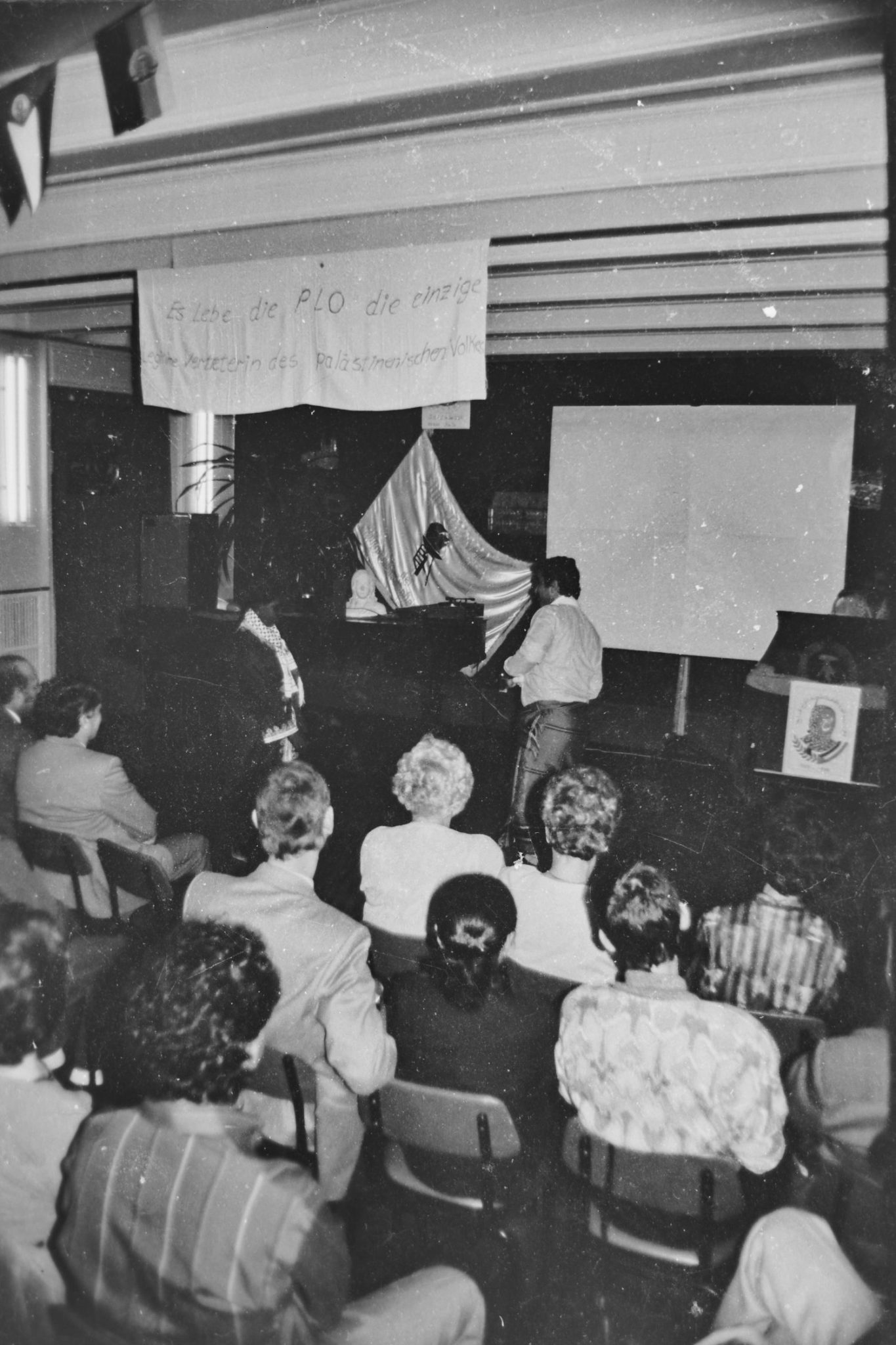

The students from the Global South were not strangers to society, nor were their struggles. Many GDR citizens were well informed about their political movements and expressed their solidarity in private contacts as well as public manifestations, such as May Day demonstrations, where Medifa students marched as the first block in Quedlinburg. At the school itself, students also organised their own political events, cultural evenings and celebrations for their national holidays.

For the inhabitants of Quedlinburg, the Medifa was also an opportunity to learn about the students’ experiences, struggles, and home countries. Fritz Kolbe, the former director of the Medifa, said in a radio report in 1982 that the international students gave GDR citizens the chance to “see our country, our people, our daily life through the eyes of a foreigner.” A powerful example of these reciprocal contacts were the Patenbrigaden (“partner brigades”) between Medifa students and the workers in public enterprises around Quedlinburg.23Regina Klein (worker at the public enterprise “Philopharm” in Quedlinburg), in discussion with the authors. 28 September 2021. Quedlinburg. And Hilde Kolbe (German instructor at the Medifa), in discussion with the authors. 6 July 2021. Quedlinburg. These brigades – which Medifa instructors had organised on their own initiative – gave students the opportunity to visit the socialist enterprises and experience in a very concrete way the different practices that the changes in ownership relations had brought about in East Germany. The students could participate in the production processes and learn about how the enterprises maintained their own health, childcare and sports facilities. East German workers, in turn, could attend German classes at the Medifa and discuss with students the developments in their home countries and movements. The students were also able to go on holidays and excursions in the GDR, attend cultural events and get to know the everyday life of the population. It was common for students to be invited to parties or even family homes over the holidays.24Soumaya Kharrat (Lebanese doctor who studied at Medifa in the late 1980s), Zoom interview with the authors. 16 September 2021. Berlin/Beirut. “We were mothers, we were sisters, we were friends, acquaintances, everything,” recalled Hilde, one of the Medifa’s German instructors.25Hilde Kolbe (German instructor at the Medifa), in discussion with the authors. 6 July 2021. Quedlinburg. Such personal relationships reflected and strengthened the ties between the countries and progressive organisations.

The students were also able to learn from the GDR’s experiences in constructing socialism and could take these insights back home. Many who studied at the Medifa during the end of the 1980s were very aware of the break that the end of socialism represented. They could not understand why the East German population was putting its advancements, its preservation of peace, and its guaranteed social and cultural rights at risk. As Soumaya, who came to study at the Medifa through the Lebanese People’s Aid, said:

“Many young people told us that West Germany was better than the GDR. And we said: No, West Germany and Lebanon are the same. The GDR is completely different – you have a completely different life here. You live in safety and can go to school. You don’t have to worry about an education, and you don’t have to worry when you go to hospital. Some said they were happy in the GDR. But some would say, “We have nothing.” To which I say, “What do you mean, you have nothing? You have everything! No Pepsi or Coca-Cola? You have lemonade, it’s the same! Only the name is different.“26Soumaya Kharrat (Lebanese doctor who studied at MediFa in the late 1980s), Zoom interview with the authors. 16 September 2021. Berlin/Beirut.

V. One building block in the worldwide anti-imperialist struggle

With the end of the GDR, the Medifa’s doors were also closed in 1991. The school and its international significance were erased from public memory thereafter. The students, teachers, and staff that we met all associate positive and exciting life experiences with Medifa, yet its political significance and impact are given no recognition in the public sphere today.

“It was about standing together for peace, for progress, and for social justice. That’s the basic definition of what we understood proletarian internationalism to be. Living it was a daily task for everyone and it was practiced differently.“27Ulrich Kolbe (German instructor at MediFa in the late 1980s), in conversation with the authors. 6 July 2021. Quedlinburg.

The states of the socialist camp could not develop in isolation. The social and political progress of socialism depended on the advancement of the struggle against imperialism worldwide. Conversely, the liberation movements and former colonies were dependent on the assistance of the socialist states in the construction of independent structures and the emancipation from imperialist dependencies. The Medifa is an example, an instrument through which this cooperation was realised. It was not an act of selflessness or charity, as “development aid” is often portrayed to be today, with a barely concealed paternalism that stands in stark contrast to the eye-to-eye relationship that developed between the GDR and the newly liberated states. As the past 30 years have shown, the practical effect of the West’s “development aid” is not to close the inequality gap between countries and societies, but to reinforce and even exacerbate it.

The GDR’s approach, vividly illustrated by Medifa, was fundamentally different. It was based on genuine assistance that simultaneously functioned as an instrument in the common struggle against imperialism. When discussing the Medifa and the GDR’s solidarity work, we often asked ourselves about the concrete impact that such initiatives had on the newly independent states and liberation movements. Yet this question ultimately overlooks the essence and the historical significance of internationalism. In the face of centuries of colonial maldevelopment, the impact of the Medifa was certainly limited. What is decisive, however, is that the direction of development was reversed: Not underdevelopment but reconstruction, not subjugation but sovereignty, not brain drain but education – these became the benchmarks of international relations. This reversal of the historical tendency marks the great achievement of practical solidarity, and it can still serve as a guide for an internationalist and anti-imperialist perspective today.