Ulrich Kolbe, a former instructor, discusses the significance of the GDR’s medical school for international students

Ulrich Kolbe (*1963), whose parents had served in various foreign assignments for the GDR, grew up in an internationalist household. From 1987 to 1991, he taught German at the “Medifa”, a Medical School in Quedlinburg that specialised in the training of international students, primarily from the national liberation movements or newly independent states. Today he works as a freelance translator, editor, author, photographer, and instructor in California.

As part of our research into the Medifa, we conducted an interview with Kolbe in July 2021. In the first part, he describes the GDR’s anti-imperialist strategy in general and discusses the development of the political consciousness of GDR citizens. In this second part, we talk about the importance of the medical school itself, both for the students and for the inhabitants of Quedlinburg.

First of all, can you explain the Medifa in general terms? What was its purpose and significance?

The medical school had been training local nurses as far back as the 1950s. In the early 1960s, a group of young students from Mali arrived, opening the school to foreign students. Over the years that followed, the training of German nurses was completely scaled down and the admission of new students was exclusively for those coming from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They were largely financed and invited by the Solidarity Committee of the GDR, that is, through relationships that the Committee had built up with political parties, movements, and trade unions in the respective countries. Students also came through the FDGB, the Free German Trade Union Federation and possibly also directly through some political parties. So, the students were almost exclusively from the newly liberated states.

1960 also became known as the “Year of Africa”, in which many African states won their independence from colonialism. The Medifa’s training programme was embedded in this historical context. Until 1960, colonialism had remained rather entrenched throughout the world. Once the liberation movements had freed their respective countries, we were able to train medical staff here in the GDR – a task that was extremely urgent in the newly liberated states. After abandoning their colonies, the former rulers withdrew their specialised personnel, like doctors, nurses, and so on. You know, one could ask: How is it that the first trained midwives in, say, Guinea-Bissau were trained in the GDR? There must have been some midwives in Guinea-Bissau before that. Sure, but they were all Portuguese and they simply left the country after independence was won. This was the situation in many young national states. There were then also countries in which the struggle for liberation was still ongoing: Namibia, South Africa, Spanish Western Sahara, and Palestine.

There was little interest in students from Western countries. Surely some would have liked to train in the GDR, why not? The health system was in a very good state by that time, and it would definitely have cost less here for students from the West than in the Federal Republic of Germany or France. But the GDR government had no interest in that at the time. The Medifa was focused on real assistance in the sense of proletarian internationalism: to help the young national states and their movements. This is also reflected by the fact that we trained not only medical professionals, but also so-called multipliers. That is, medical instructors who were able to return to their countries and begin to teach others. Helping people to help themselves, which has been propagated in the West these last few years, that is nothing new. We were already practicing it.

Before they both worked at Medifa, your parents took you along when they were sent on a teaching assignment abroad. What was it like for you to grow up in an internationalist environment?

I think it was very special. At the big demonstration on 4 November 1989, a speaker coined the phrase: “In order to actually have a world view, you have to be able to see the world.” Not everyone could do that prior to that. And I could. I experienced war in the Middle East, which leaves a deep impression, especially on a child. But I also experienced beautiful things and grew up open-minded, with an interest in other languages and other cultures. That continued here in Quedlinburg in the GDR. Through their work, my parents were in constant contact with students, with progressive individuals from all over the world. It was a special, a beautiful time.

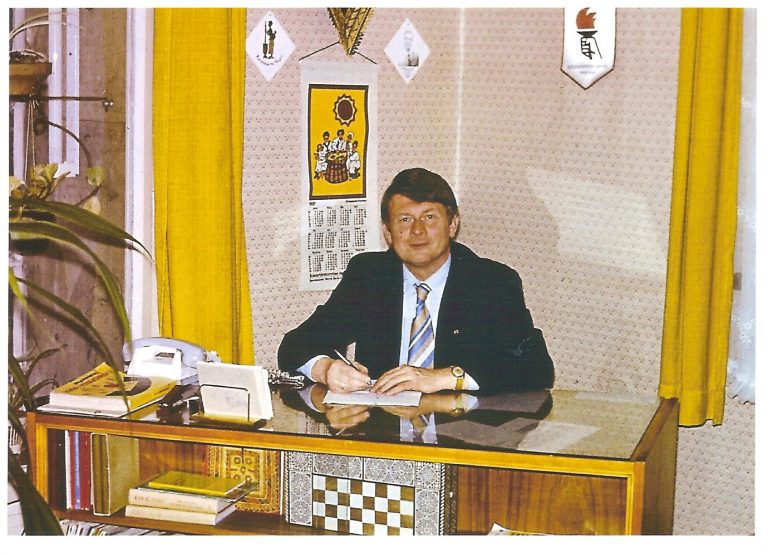

Your father was the Medifa’s head of school from 1970 onwards. How did that come about?

Both my parents had lived through the Second World War. My father was slated to be a soldier when he was very young. He learned English while in captivity. After that experience, he was first and foremost a very vehement opponent of war and, as such, he was naturally inclined towards the true and simple ideals of socialism. With this basic attitude, he first became an instructor for kindergarten teachers here in the district of Quedlinburg and then later he began teaching German abroad.

At that time, the GDR was recognised diplomatically by only very few foreign governments. This was due to the Hallstein Doctrine and other economic measures by the West. And so the GDR tried to find allies in newly independent states in the Global South. Cultural centres were established in Syria, Egypt, and Iraq, for example, which had the task of teaching the German language and providing information on the culture and life in the GDR. This was a way of preparing trainees from these countries for their studies in the GDR. That was my father’s life work. When the four years in Syria were over, he was asked to lead the medical school in Quedlinburg and continued to work there in the spirit of internationalism. Both parents had been in Berlin for the Third World Festival of Youth and Students in 1951. The organization behind these festivals, the World Federation of Democratic Youth, held up the idea of building a new society after the war, to create peace and understanding between the peoples. Such ideals were decisive for many of this generation at that time.

So, he became an internationalist through his experiences.

Yes. It was also a product of his family’s working-class background. He already had been an opponent of war before he was conscripted to join the Wehrmacht. And because he had survived the war, he felt compelled to prevent another war and combat xenophobia.

Later you also worked as a teacher at Medifa. What was that like for you and how did you prepare for it?

Well, I started at the school in 1987 as a German instructor for foreign students. I had studied linguistics before that: English, French, Russian, Arabic. But the lessons were supposed to be taught entirely in German. We did our best to arrange it that way. By that time, students from more than 60 countries and national liberation movement had already received training at the Quedlinburg school.

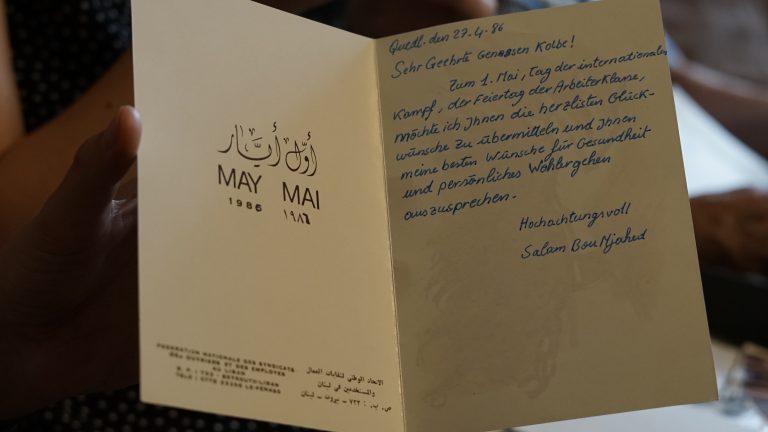

There were also delegates sent by national liberation movements such as FRELIMO, SWAPO, the ANC, POLISARIO, and the PLO. The students I first taught were a very diverse group. I was mainly assigned Palestinian, Lebanese, Syrian, and Kurdish students. But I also had students from Vietnam, Laos, and Africa. Most of them had been granted scholarships through the Solidarity Committee. There were also some sponsored by the trade union federation, the FDGB, and later, I would like to think from 1988 onwards, a small group of individuals who paid to attend the school as a way of generating hard currency for the GDR.

How exactly were the students selected? Can you say that they were people from working class backgrounds who would not have been able to get this kind of education in their countries under other circumstances?

That is correct. I think that great care was taken to ensure that the students were, as you say, working class to begin with. If they had been established doctors from upper-class backgrounds, they might have had too much to complain about in terms of the living conditions, the accommodation in the GDR, the supply situation, and they wouldn’t exactly have made life easier for other students. That was not the purpose of the school. The main objective was to help working people. That was the credo: To organize specialized medical training for those who needed it most.

Were you able to talk to the students in Arabic outside of class? Did you also talk about political issues?

Yes, and because our age difference was less significant than with the older instructors, our relationships were often more relaxed and cordial. It was also less complicated to talk to them about political developments. They treated the older German instructors with a little more respect and reservation.

Our discussions were, for example, about the differences within the Palestinian Liberation Organization PLO, the PFLP, the DFLP, and the Palestinian Communist Party and its relationship to Fatah, but in general, also the role that this movement had played in the lives of the young people. They would bring it up and would want to know my opinion on it. I had to respond somewhat diplomatically, of course. And I didn’t represent the GDR in the sense of acting as a political advisor.

Can you tell us more about the content of the lessons? What were the students interested in and what topics did they want to talk about with you in relation to the GDR?

Landeskunde (cultural studies) was an accompanying subject to German for foreign students. It was primarily listening comprehension, reading comprehension, conversation and then questions and answers along those lines. So they were able to ask questions about everyday life in the GDR or it was first explained to them how things worked. In May 1989, for example, the first elections took place in the GDR in which non-citizens were allowed to vote and as they had already gotten to know they country, they made good use of this opportunity. Of course, some of them were surprised. They would have liked to see some candidates crossed out or some parties not on the ballot papers and were surprised to find that this was not easily possible under the GDR election regulations. Instead, all they had to do was fold the ballot paper and put it in the ballot box. There were interesting discussions afterwards about whether that was an election at all and what constituted an election. And that was always quite interesting for all sides.

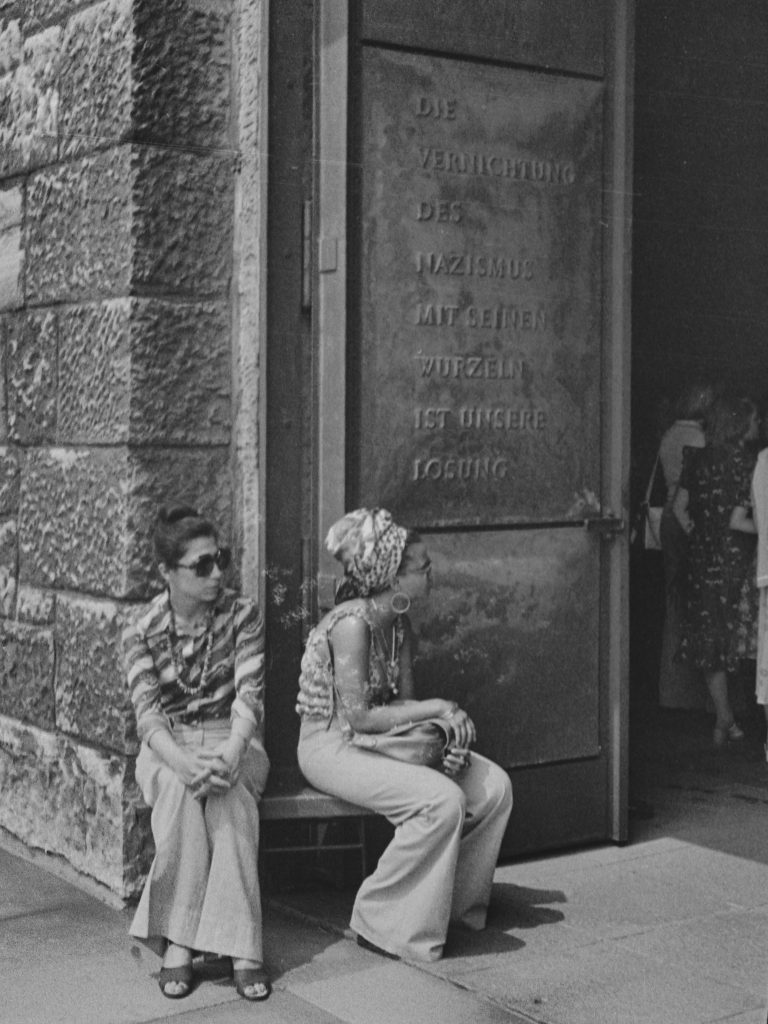

Cultural studies was also based on excursions, on class trips. So almost all the groups that received their training at the medical school went to the National Memorial Site at the former Buchenwald concentration camp at some point or to memorials in the immediate vicinity. The idea was to convey this part of history to the students and give them a feeling for the experiences and principles upon which this state had been founded.

What impressions did the students get from these excursions? What did you discuss there?

It was interesting for me and the other GDR teachers, because many of the students had also experienced terrible things in their home countries. The siege of the Palestinian refugee camps in southern Lebanon and so on. They compared what they saw when visiting our memorial sites here with their own experiences. That was something we hadn’t expected and, in this way, the effect that these memorials had on us in the GDR was minimized a little – by their being able to say, “In our family, too, everyone was killed, by the Falangists or by the Israelis – we don’t have such memorials, but we understand you.” Their words did not devalue or negate the memorial in any way, but it was interesting that the current political events of the 1970s and 80s could suddenly be reassessed through the lens of German history.

So, there was also an exchange about what was happening in their home countries?

Yes, for some students, their time in the GDR offered them the opportunity to express themselves freely for the first time. Even just to write articles for a bulletin board or give a speech about the problems in Kurdistan. Of course, this would not have been possible anywhere else at that time, and today in the Federal Republic of Germany it is not exactly welcomed when people talk about Kurdistan. That alone gave them a feeling of being highly valued and recognised.

Did your contact with the students continue after the Medifa was closed in 1991?

Yes. There were many very heartfelt letters in which students would report on the work they took up after returning home. There was a mother and her daughter, I think from Cape Verde, who had both been students in Quedlinburg and then became the first midwives there. Similar letters continued to arrive, some even decades later after the school had closed. Some former students showed up in person, wanting to see what had become of the teachers after hearing about the events of this so-called “German unification”.

Was the end of the GDR an issue for many of the former students?

The discussions, at least in the classes I taught at the time, were quite heated and also carried by great dismay. As I said, they came from Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon or Jordan or from Kurdistan and had often embraced the GDR as a second home, whether politically or in everyday life. And that this home was now going to be dismantled for… for what, actually? They couldn’t understand why some GDR citizens were willing to risk their social achievements — and above all, the peace that had existed for 40 years — in order to buy a few Western consumer products in the shops. Some of the Lebanese students told them: we too have access to these commodities but look at the rest of our country!

They knew exactly what was coming. I was told about one of my final students, a Palestinian, that he had confronted some high-ranking representatives of the new German Department of Foreign Aid by stating right in their faces, “If I had known that I would not finish my studies in the socialist GDR but in the imperialist Federal Republic of Germany, I would never have come here.” I was quite pleased by that!

Do you think the GDR did justice to the task it had set itself?

I think so. Absolutely. That was clear from the letters I just mentioned, the feedback we received and the visits after many years. The vast majority of the students in Quedlinburg, and in the other institutions of the GDR, had acquired the tools they required to help build up their own countries. After all, health care and protection are some of the most elementary human rights. And that is where the GDR came in and proved to be a reliable partner.

How did the solidarity of the GDR differ from what they call “development aid” today?

On the one hand, the students and trainees became acquainted with a completely different, a new social system in which people, not profits were prioritized. Of course, if you come from Africa, you can major in Medicine in Germany today if you have the necessary money and connections and have learned the language somewhere. And it’s very likely that afterwards, you won’t feel the urge to return to your country after experiencing the “Western lifestyle”.

Those who came to the Medifa were cadres, as they were called at the time. They were people you could rely on: they wouldn’t let themselves be seduced and misled, but would return home, even if they had been able to enjoy four years without bombings and without hunger. They knew and understood that they owed it to their people. This attitude was something completely different from what bourgeois development aid brings about today. Western society is about profit and not about human lives.

It was different in the socialist states. Our actions were not profit-oriented. From today’s capitalist managerial perspective, the Medifa was obviously not a profitable enterprise. But you can’t see it like that. People were helped here, who in turn helped other people in the countries plagued by poverty. And they are still helping people today! That should be at the forefront of any project today, not the question of how much money can be made.

The interview was conducted in Quedlinburg on 07.07.2021. It has been edited slightly for better readability.