Interview with Achim Reichardt, the last director of the GDR’s Solidarity Committee

Achim Reichardt, born in 1929, served as a diplomat for the GDR in Sudan, Lebanon, and Libya. From 1982 to 1990 he was general secretary of the Solidarity Committee of the GDR, an organization that emerged in the 1960s to administer the financial and material donations collected by the GDR’s mass organizations in support of the liberation movements and newly independent states in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The Solidarity Committee became a central coordinator of the GDR’s internationalism throughout the world. After 1990, Reichardt endeavored to ensure that the remaining financial resources of the Committee – donations from GDR citizens – continued to be used for meaningful support in the Global South.

How did internationalism come into your life, or how did you first experience it?

When you enter political life, you sometimes don’t know exactly where your path will lead, which direction you should take. But once you become active, as I did immediately after the war as a young man, first in local politics, where my father was appointed as a town mayor by the Soviets, then you realize what mutual support means. If I think back to my first international contacts, they were with the Soviet officers of the time, who supported the mayors and municipalities in the villages. It made a special impression on me that the Soviets helped us, the young people in the GDR, even though in their homelands, they had most certainly experienced quite different things at the hands of the Germans. This impression continued and strengthened over the years: you felt you were being supported and tried to give something back. Personally, I tried to make contact with the Soviets during each of my deployments. The lasting memories that are burned into my mind are from my time in Libya, where I effectively had no base and had to build everything from scratch. This would not have been possible without the help of Soviet, Czech, and Polish friends who were very active there. Even later, you somehow always sensed that people who were on the left were striving to support each other, and that was the decisive thing for me.

How did the Solidarity Committee come into being and develop?

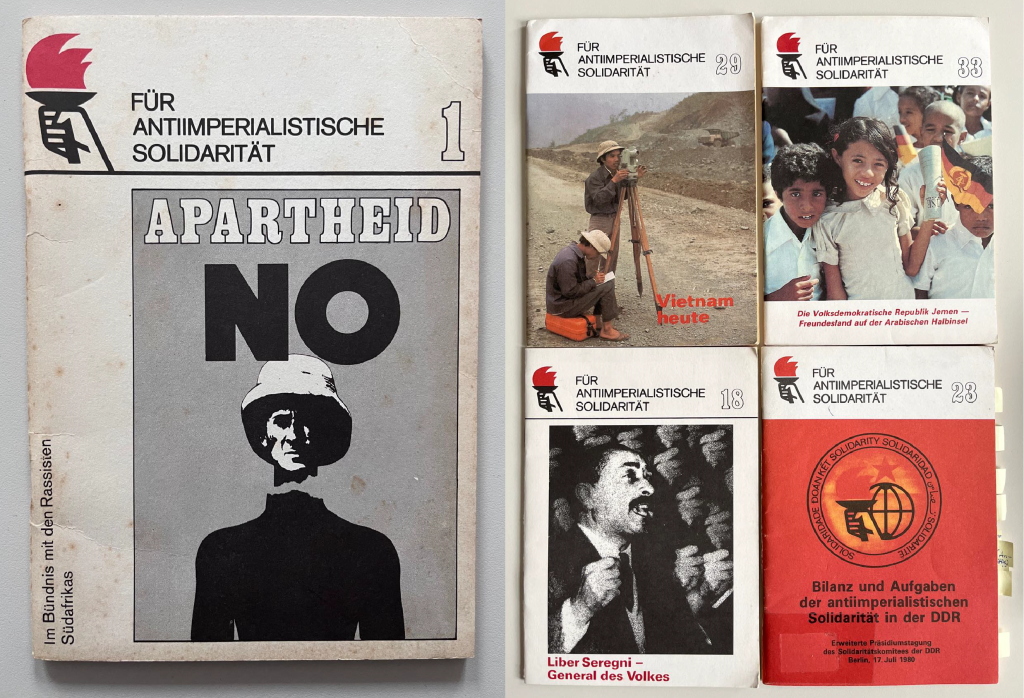

The Solidarity Committee did not exist in the GDR from the beginning. After 1945, it was first the new mass organizations, the trade unions, also the women’s organizations, that sent solidarity contributions to organizations with which they had contact. These self-directed developments continued, and it was not until the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, when the liberation movements on the African continent became stronger and some states had gained independence, that the Africa Committee1The Solidarity Committee for Africa was established on July 22, 1960 and was a precursor to the Solidarity Committee. emerged as an organ in its own right.

The Solidarity movement de facto developed alongside the international conflicts: After Africa came Vietnam, later Chile, and there was always a demand for solidarity, and it became apparent that the individual groups and organizations alone could not handle the matter. Therefore, other options were explored and gradually the Committee was formed including the Vietnam Committee and the Solidarity Committee for Chile. Long before I came to the Solidarity Committee, it was formed as a non-governmental body.

It became apparent early on that it was mostly international activities that the committee was pursuing, because within the GDR, Volkssolidarität2Volkssolidarität – People’s Solidarity, aid and mass organization for the care of the elderly in the GDR. had emerged. Support within the GDR was therefore not on the agenda of the Solidarity Committee. It was essentially about how to inform the population. There were a great many activities in this area, by the parties, mass organizations, trade unions, women, FDJ, Young Pioneers. Above all, schools, i.e., teachers, got involved with solidarity work and informed children. When I started my work in the Solidarity Committee, I tried to make personal contact with every organization, especially with the trade unions. Large companies approached the Solidarity Committee and asked whether one of us would come by and talk about solidarity in the union groups. Journalists regularly reported on the solidarity work in the company and regional newspapers.

Why was the Committee not a governmental institution? What did this status mean?

It has to do with the fact that the whole movement was created through donations. I remember, for example, that the trade unions had organized a donation for a partner organization in an East African country. Or when I was working as a diplomat in Sudan, I got to know that our farmers’ organization had contacts there, and so on. Such contacts meant that it was below the state level. At the same time, the state played a key role in facilitating our work. For example, the Committee was allowed to pay for transport in GDR marks rather than in foreign currency, which was usually the case. The Ministry of Finance sorted this out with Interflug (the GDR’s state airline) for us, because we had no foreign currency of our own. The same applied to solidarity supplies that were shipped.

Through conversations with my predecessors, I learned that there had also been state support to pay for personnel costs in several cases. But in my time, the flow of donations was so great that we did not need to draw on additional government support other than paying for shipments in GDR marks. We were able to prove that our administrative costs — compared to the total volume of solidarity — never exceeded 2%, usually only 1%. This also meant that the donations could be effectively deployed.

There was close coordination between the Solidarity Committee and the GDR’s embassies or trade missions overseas. The embassies, for example in Mozambique or Ethiopia, would hear from their contacts what was needed. That was one direction. And the second direction was that the Solidarity Committee maintained close relations with the respective organizations in these countries.

How did the Solidarity Committee inform the GDR population about its work and what did internationalism mean to them?

I emphasize it again, the decisions on how and where the Solidarity Committee should conduct its activities were made in consultation with the respective mass organizations. The representatives of the trade union, women’s organization, etc., always agreed on the plans for the work of the Solidarity Committee in terms of national political activities, and also on the priorities of material solidarity. With the support of the broad mass organizations and parties, there were very many events — independent of the Solidarity Committee — on news in Vietnam, on the Korean War, and later on Africa. I can’t remember much of it, but you would only have to look again in the newspapers of that time to see what was going on. There were also central solidarity events in which the committee and I as general secretary participated. These were about Vietnam and Korea, then the PLO, Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique… all the countries where the struggle for independence and against oppression was taking place.

When I started working for the Solidarity Committee, I was faced with the question of how the work had been done so far and what could be improved. I noticed that there were so-called permanent donors to the Committee, but that there were also many donations from groups, from the schools, from National Front3National Front – the coalition of all political parties and mass organizations in the GDR. residential communities, and also from political parties. This did not yet include the solidarity of the trade unions, but only what went directly to the Solidarity Committee. At that time, we discussed in the circle of those responsible how we could be broader in our reach and, with the help of the trade unions, began to go into the factories as well. This proved particularly effective, because in many companies there were young people from other countries and for us it was not always just a matter of talking and handing out information. We used this interest and the possibility of exchange to get in contact with the trade union groups and to inform about solidarity. We then continued this work in the schools because there were also many active student groups.

All my colleagues were active in some groups outside the Solidarity Committee. There you could feel that the GDR population was really involved. Their attitude was: We are slowly overcoming our time of hardship, but in other countries, their hardship continues and is even greater than ours. There were many such experiences… As general secretary of the Solidarity Committee, this awareness prompted me to get involved directly, not just to send out my colleagues. Several hundred people from all walks of life always took part in the annual reports of the Committee during its presidium meeting. The sponsors of the Committee – the trade unions, the women’s and farmers’ organizations – contributed a great deal to ensuring that our work and activities were reflected in their circles.

What solidarity projects and experiences do you remember most?

That’s difficult. One of our strongest bonds was with Vietnam. It was essentially about the Vietnamese being able to rebuild their country after independence, after the wars had ended. We asked what they needed, and we couldn’t always fully meet their needs, but in essence our task was clear. Above all, it was about training young people in the GDR. I can still remember the Moritzburg4Moritzburg – a location close to the city of Dresden where in the 1950s a school was established for 350 Vietnamese children fleeing the war. in Dresden very well, because I later met some of the children. The young Koreans and Vietnamese who received their education there later took up important roles in political and social life in their countries. As far as Korea was concerned, the Solidarity Committee, together with the GDR’s State Planning Commission, coordinated economic aid to the country and financed it from the Solidarity Fund. In the early 1980s, my predecessor co-signed an agreement with Vietnam. This was another example of combined actions between the state and the Solidarity Committee.

It was an honor for the Solidarity Committee that representatives from these organizations and countries, when they were in the GDR, paid us a visit. This happened for example, when Namibia’s Sam Nujoma came, or the ANC’s Secretary-General Alfred Nzo, and so on. Even Yasser Arafat, whom I had already met, always came to the Solidarity Committee for a meeting when he was in Berlin. When I was invited to Namibia for the declaration of independence in 1990, I had the honor of talking to Nelson Mandela. I told him where I came from. And he said: “I will never forget the youth of the GDR. They wrote me so many letters, cards, and so on.” I must say that was impressive. A person who had been behind bars for 24 years had taken note of the GDR’s youth movement.

One big action that I still remember fondly was the hospital in Nicaragua. That took a lot of work from our colleagues who helped to build it. The lion’s share of the work had been done by the GDR’s National People’s Army, because they built a field hospital there. The Solidarity Committee then had to get actively involved in supplying materials for the hospital and for the staff. I am convinced that this was a very important action. Following the GDR’s demise, I had talks with those responsible on the Federal German side, who told me that such a project was too demanding for them. As far as I know, it was then privatized in parts. At that time, there were also doctors trained in the GDR who worked in the hospital for a short time and were eventually poached by the Western side. There was always this hard struggle.

What role did the Committee play in the development of the hospital?

There was very close cooperation with the FDJ and its friendship brigades, also with the Ministry of Health and the relevant agencies that were necessary to develop the hospital. After all, it did not remain a project of the army, which withdrew after the construction. Instead, it became a great object of solidarity that still has an impact in some form today. And there were similar, small projects in other countries, for example in Ethiopia. There, a health station was built far away from the capital. When I was in Ethiopia, I was invited to visit the station. It was difficult to reach and could only be supplied by airplane — we flew over endless green forests and mountains. It was important to build structures not only in the centers.

How were projects generally brought to the attention of the Committee or how were they initiated?

The Committee itself had contacts with progressive organizations in the respective countries. However, I had already referred to the close cooperation between the embassies and the Committee: The GDR Foreign Ministry had allowed the Solidarity Committee to correspond directly with the embassies, which was a great advantage. Embassy meant not only the diplomatic representation, but also the commercial representation, who also had contacts. The applications that came in were collected. There were also international conferences, where mostly the official representatives of those organizations were present and important correspondences arose. It is difficult to trace this in detail, but I can only keep reminding you how often Sam Nujoma, when he was in the GDR, also came to the Solidarity Committee. That had a political effect as well.

The GDR had a UN representation and could be found in important international organizations. Crucial information and requests to the Solidarity Committee to support the respective countries also came from there. This concerned, for example, the WHO or educational work. We oriented our work around these requests, responded to them and assessed their viability: was it possible or not?

We also had very close cooperation with the solidarity committees from Finland, Denmark, and Norway. In cooperation with these organizations, we actively worked together, for example, to build kindergartens and send teachers. Within the GDR, of course, this was done in coordination with the specialized ministries; you can’t do it without them. On the whole, this turned out to be positive… The Finns also managed many deliveries, where we as the Solidarity Committee could not get to for financial, currency-related reasons. They loaded materials in Helsinki onto GDR ships, which were reloaded in Rostock or Warnemünde in the GDR and then went down to Africa. This kind of cooperation also worked out well.

How did the recipients receive solidarity, how did it arrive in concrete terms?

We attached great importance to the fact that the recipients were actively involved in the solidarity contributions and that certain material supplies were not squandered or converted into money. I can still remember reports from Mozambique and Nicaragua at the time that the benefits really did reach the recipients and the masses. In my book I wrote about the example of our Jupp Jeschke, who had very good relations with Nicaragua. He was invited to visit a remote area together with journalists where at that time there were still clashes with opposing forces. He was introduced to the people in the village when suddenly a woman screamed “Wait, wait!” and ran away. She came back with her children and said, “Look at this man, he sent you the schoolbooks!” And that was a sign for us — and it wasn’t the only one — that the textbooks were really distributed far into the country’s terrain and not just left somewhere in the capital.

There were also requests from many partners where we had to say from the outset: We cannot manage that. For example, there was the wish to build a hospital right away. But building a hospital does not only mean putting bricks on top of each other, but also providing the substance, i.e., doctors, nurses, etc. In this respect, the GDR played a positive role in training young people at the medical school in Quedlinburg.

How did you decide whether to support a cause?

When we wanted to implement a solidarity project, we always kept in mind what the wishes were and asked: does this project serve the overall development of this country? I was giving the example of the hospital in Nicaragua, and it also applies to Vietnam, for example. There, we intensively supported the hospital in Hanoi and helped to build an institute that provided care for the many people in Vietnam who had lost legs or other limbs as a result of the war and the mines. When I was in Vietnam in 1985/86, I visited this institution, and they were very grateful that many Vietnamese could walk again. We also carried out such measures in other countries.

For us, the main focus was on liberation movements and countries that had begun progressive development and wanted to move forward. But there were also actions of the Solidarity Committee aimed at providing humanitarian aid in cases of severe climatic changes and disasters, but the big problem for us was: In these cases, we sometimes did not know if it would reach the recipient at all, because there were no other established relations. That’s why I mentioned the example of Nicaragua in my book, where it was not only a matter of sending people there, but also of directly developing a training school so that plumbers, installers, etc. could be trained locally. And that was always the direction we were looking at.

How did the solidarity work change after the end of the GDR?

It was difficult to continue the work at SODI5SODI, Solidaritätsdienst International e.V. – successor organization to the Solidarity Committee, a development aid association. in the way it had been done at the Solidarity Committee… I also experience the problem here in my hometown: There were two associations for Gambia that have nothing to do with the government. This is a private contact that was developed and what they do is positive. But it’s just a small operation. When I look at SODI today – even though they are still active in the countries that we mainly supported, Vietnam and so on – but suddenly a small operation emerges in Congo; there’s a little project popping up in India; arising through private contacts. And that is in fact what we did not do. If there is an association and a village, and there is someone who wants to develop the village, that is positive. But if I invest 1,000 €, 2,000 € or 5,000 €, not much happens. Therefore, the humanitarian work today tends to be more a drop in the bucket; support is distributed here and there. We ourselves always admitted that our solidarity is just a drop in the bucket, but we sought to ensure that it would at least serve to develop something. Not just the small farmer or the small village or the kindergarten – while that is beneficial! But we should consider the situation in its entirety. I sometimes shake my head at the small projects I see here and there and when I look at it that way, the commercial aspect is always attached to it. What I realized in the years after 1990 in the Federal Republic of Germany: There is no point in working alone on certain actions. When you see the television appeals for large aid projects, where three or four large organizations throw the collected money into one pot, it is still always about individual small projects.

As the Solidarity Committee, we of course also visited the respective countries, either in connection with the projects or sometimes for stopovers, in order to make contact with the partner organizations. The interesting thing is, we as the Solidarity Committee were treated like state guests. Representatives of the Solidarity Committee were received by ministers. This happened to me personally when I was in South Yemen, and I was totally surprised. I was invited to meet the president, and he thanked me for all the solidarity that the GDR had provided at each level, where certain measures were also state measures. The recognition of the achievement as that of the Solidarity Committee – that is, of the GDR citizens – was admirable.

The IF DDR conducted two interviews with Reichardt on 23.02.2021 and 06.04.2021. They have been edited slightly for better readability.