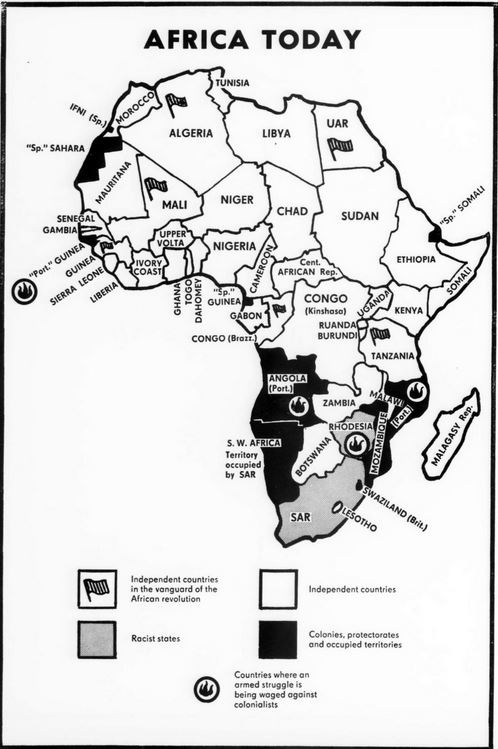

From 1960 to 1968, the Republic of Mali was at the forefront of social revolution in Africa. The country’s governing party, the Union Soudanaise, had refused to settle for formal political sovereignty and declared in 1960 that the republic would opt for “l’option socialiste” to secure economic independence from imperialism and social liberation for the Malian people. Since its inception, the national movement in “French West Africa” had maintained close links with the international communist movement. Many of its leaders had organised the Groupes d’Etudes Communistes, study cells that had spread throughout West and Equatorial Africa in the 1940s with the help of the French Communist Party. After Mali and Guinea won independence with anti-imperialist parties at the helm in the late 1950s, this relationship took on new dimensions. The socialist camp now began to support these young state projects in their endeavor to overcome neocolonial exploitation and, ultimately, circumvent the capitalist stage of development.

This brief episode of revolutionary upheaval in Mali offers insights into several central aspects of anti-imperialism in the 20th century. Firstly, it gives an idea of the nature of relations between the socialist camp and progressive governments in the newly liberated states. Both shared a common enemy in Western imperialism, but how far did they go in coordinating their actions and discussing tactics? Secondly, developments in Mali help to reveal the internationalist strategy of communist forces at this historical crossroad in the 1960s. Theories such as “non-capitalist development” and the “national democratic state”, which would become central concepts in the communists’ analysis of the former colonies, were fleshed out at the beginning of this decade. Finally, the trajectory of Mali’s ruling party, the Union Soudanaise, from an anti-colonial mass movement towards a vanguardist party is illustrative of how class struggle unfolded during the second stage of national liberation. As explored below, the question of finding an appropriate form of political organization for the struggle against neocolonialism was at the centre of debates amongst revolutionaries in Africa at the time.

Any conclusions drawn from just one example will of course be preliminary; it will be necessary to compare experiences in Mali with those in other national democratic states.1To name a few examples: Egypt, Algeria, Syria, and Afghanistan. And, to a different degree, also the Central Asian Soviet Republics, Mongolia, China, and Korea. Mali is, however, a significant instance, for the Union Soudanaise was the first governing party in the newly liberated African states to identify Marxism-Leninism as its ideological basis and de facto align with the socialist camp by the mid-1960s. Research for the following article was based largely on DDR and SED documents found in the Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives), articles in communist journals such as the Problems of Peace and Socialism, and analyses by both liberal and Marxist historians. Specific sources, longer quotes, and additional information can be found in the footnotes for those interested in further research.

Although the article focuses primarily on the eight-year period of revolutionary democracy in Mali, it also covers important developments running up to Mali’s independence and explores several aspects of the option socialiste. A condensed version excluding agricultural reforms and ideological debates in the communist movement can be found here.

The maldevelopment of West Africa through European exploitation

Western Africa was once home to some of the most advanced societies on the African continent. From the 5th century to the end of the 16th century, successive states had developed large economies based primarily on agriculture, handicrafts, and the gold trade. By the 16th century, early feudalist tendencies in West Africa (e.g., the emergence of an aristocracy based on the exploitation of village communities) had begun to erode but not yet fully replace communalist egalitarianism.2For a broader Marxist overview of this period in West Africa, see the work of the Guyanese historian Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, (London: Verso Books, 2018) and the French historian Jean Suret-Canale, e.g., “Die Bedeutung der Tradition in den westafrikanischen Gesellschaftsordnungen” in Tradition und nichtkapitalistischer Entwicklungsweg in Afrika, ed. Irmgard Sellnow and Helmut Mardek, 107–139. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1971. With the arrival of European slave traders in the second half of the 16th century, the region violently descended into an era of foreign exploitation and subjugation. Until the mid-19th century, the West African coastline was a central node in the transatlantic slave trade, while the hinterland became a hunting ground for captives, who were then sold to Europeans in exchange for consumer goods of little value. This pre-colonial era thoroughly distorted the development of West Africa, for it not only stripped the region of its labour force, but also reoriented internal economic activity around the highly destructive practice of slave hunting.

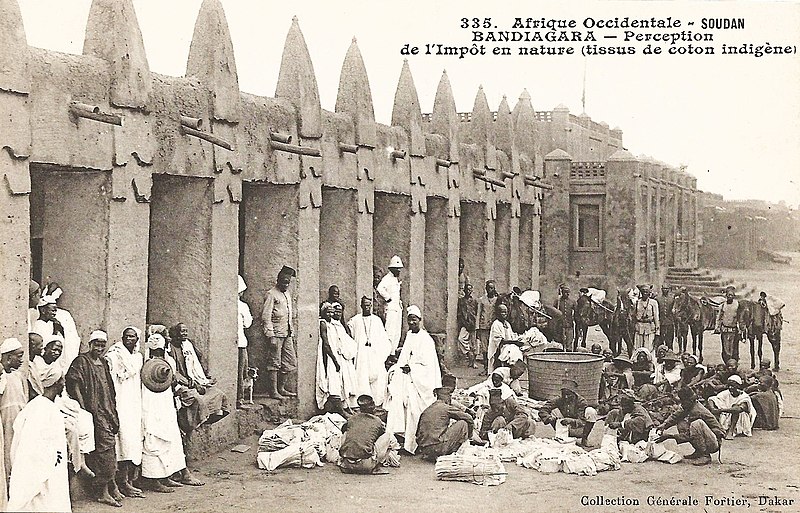

In the 1870s, the French began establishing forts and outposts along the Niger River, taking direct control over large swathes of West Africa. The shift to colonial rule meant the direct integration of West Africa into the imperialist world economy; the labour force was now to be exploited at home, rather than exported abroad. Groundnuts became an early cash crop in “French West Africa” before colonial authorities attempted to establish cotton projects along the Niger River, with the forced resettlement of local families to work the land.3Klaus Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1973).

French colonialism distorted the West African economy in a very particular way. Unlike the colonizers of East and South Africa who broke down communalist relations and created a class of expropriated labourers that could work in extractive industries or quasi-feudal plantations, France exported little capital into West Africa and limited its direct involvement in the sphere of production.4France preferred to export capital to Eastern Europe and Russia (pre-1917). When they did export capital to West Africa, it remained in coastal territories in Senegal and the Côte d’Ivoire where the French constructed some large plantations that would later give rise to a type of agrarian bourgeoisie in these states. Suret-Canale, “Die Bedeutung der Tradition in den westafrikanischen Gesellschaftsordnungen”. French trading companies instead relied mostly on the imposition of unequal trade to extract a profit: buying up compulsory agricultural produce at low prices and selling inferior consumer goods at high prices.5It is upon such exploitative practices that some modern-day monopolies such as the UNILEVER corporation or the Compagnie française de l’Afrique occidentale (today the “Corporation for Africa & Overseas”, CFAO) rose to prominence. Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Village and canton chiefs were selected and bribed by the French to enforce colonial rule and represent the interests of the trading companies. As a result, village communities in West Africa were subordinated to the needs of foreign monopolies, but their semi-communalist mode of production remained largely intact. The West African economy thus embodied stark contradictions by the end of the colonial era: on one hand it was directly integrated into the imperialist world market and on the other it was still characterized by pre-feudal village structures based predominantly on subsistence farming, common ownership of land, and patriarchal relations.

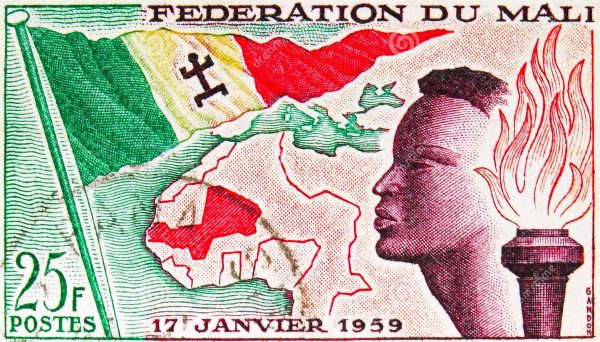

By the 1950s, the independence movement in West Africa had won significant concessions from France. The Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA), a coalition of parties from throughout French West and Equatorial Africa founded in 1946, played a crucial role alongside the French Communist Party (PCF) in pressuring the French establishment to accept political autonomy for the colonies. The RDA section in “French Soudan” (modern-day Mali) was the Union Soudanaise (US-RDA). The party had been co-founded by Modibo Keïta, a young teacher from Bamako who had been active in the PCF-affiliated “Communist Study Groups” (Groupes d’Etudes Communistes) in his home city. Keïta came to lead the independence movement in French Soudan and won autonomy for the new Sudanese Republic through a referendum in 1958. As a pan-Africanist, Keïta advocated for the integration of the former colonies of French West Africa. The Mali Federation, a union between the Sudanese Republic and Senegal, was formed in early 1959, but the leaders of the two countries had divergent visions for the future, with the Senegalese favoring a capitalist development and closer relations with France. After only a few months, the union disintegrated, and the US-RDA declared an independent Republic of Mali in September 1960. The failure of the Federation marked a significant blow to the US-RDA, as Senegal represented Mali’s gate to the world. The capital (Bamako) was now separated from the coast by almost 1000 kilometers, a fact that would plague the Malian economy for decades to come.

The US-RDA and the international communist movement

The US-RDA was a mass party operating as a national front. It had formed after a series of mergers between various political groupings influenced by the social democratic Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière (SFIO) or the Marxist-Leninist PCF. 90 percent of US-RDA members were peasants, while the leadership predominantly came from petty-bourgeois backgrounds (e.g., teachers, doctors, and clerks).6Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf. The nascent working class, which made up only 2.8% of Mali’s working population at the time of independence, had a relatively minor presence in the party but was able to exert some influence through the Union Nationale des Travailleurs du Mali (UNTM), the party-affiliated trade union. Immediately following Mali’s independence, a US-RDA congress announced a second stage in their struggle for national liberation, stating that the country must “immediately and resolutely undertake economic de-colonization, to establish as soon as possible a new economic structure and, on the basis of the concrete possibilities of the African countries, to develop trade relations within the framework of socialist planning.“7Extraordinary Party Congress of the US-RDA on 22 September 1960, quoted in Economie et politique, Nr. 96, 1962, p.89 (Bundesarchiv DQ_1_23938) Now that formal political sovereignty had been achieved, the task was to drive the country towards economic independence and social emancipation to “rid the people of the legacy of colonialism”.

As Mali’s first president, Keïta initiated a series of measures as part of this option socialiste: key sectors of the formerly colonised economy were nationalised and integrated into a five-year plan (1961–66), a new currency was created to break away from France’s neocolonial CFA franc zone, and an “action rurale” was launched to transform the semi-communalist villages into modern agricultural cooperatives. These initiatives were to be the first steps in a three-stage revolution in Mali: an initial “socialist transformation” of existing conditions, followed by the “construction of socialism”, and finally the “consolidation of socialist society”.8See Idrissa Diarra, “Massenpartei und Aufbau des Sozialismus”, Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, iss. 01, 1967.

While the US-RDA had been the first non-communist party in Africa to identify Marxism-Leninism as its ideological basis, it remained a socially and ideologically heterogeneous “patriotic front”.9The following summary is based on Ernst’s 1973 book and documents found in the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv DY 30/98101 and DY 30/98099). Both sources based their analyses on primary research in Mali and on reports in L’Essor, the US-RDA’s newspaper. Prior to independence, all classes and social groups in Mali (with the exception of the corrupted chieftains) had found themselves in contradiction with foreign imperialism. After political independence had been secured and national construction was underway, class differentiation began to intensify, and factions started to crystalize within the party. A right-wing tendency held a relatively strong position in the party’s leadership, with roughly half of the seats in the politburo and several key ministerial posts. This group did not openly challenge the option socialiste but pushed for more moderate reforms and a less antagonistic relationship with France. A left wing of the party was sustained by those who had been active in the PCF’s Study Groups that had merged with the US-RDA in the late 1950s. This leftist tendency soon drew support from the party’s youth wing (the JUS-RDA) and trade union members. They did not have an independent political platform and instead advocated for the rigorous implementation of the option socialiste.

The US-RDA had been more defiant than most other governing parties in neighbouring states, but it had never broken with France entirely. To maintain their influence in the country and exacerbate disagreements in the US-RDA, the Western powers began to offer financial credit to Keïta’s government in the early 1960s. Mali subsequently joined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in 1963 and signed an association agreement with the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1964. The socialist camp had few illusions regarding this question, recognizing that colonial maldevelopment and the limitations of Soviet resources put Mali in a difficult position in which the US-RDA sought to “manoeuvre politically between the two world systems.“10 (quote)Quoted from an internal East German assessment from 1965 (DY 30/9810). A similar assessment was also made in early 1968: “Due to the complicated economic situation of Mali and the limited possibilities of the socialist countries to provide help, the Malian leadership sees itself forced to call on the help of imperialist states (France, West Germany).” Although Mali was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, President Keïta emphasised in the early 1960s that this did not equate to neutrality: “Indeed, we are a non-aligned country, but our non-alignment does not translate into a tightrope walk. Our nonalignment does not mean silence in the face of imperialist aggressions. Our nonalignment does not mean remaining mute to the violation of the rights of peoples, of citizens. Our nonalignment also does not mean that we retreat internally in the face of a cultural action aimed at eliminating the socialist countries, the communist countries, denigrating them as countries of disorder.” (quoted in Argumente und Tatsachen, Zur Entwicklung der afrikanischen Parteien (Berlin: Zentralkomitee der SED, 1965), 29.)

The international communist movement at this time was still enfeebled by the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943 and then the Cominform in 1956.11The Communist International (Third International) was dissolved in 1943 during the height of the Second World War. The Cominform (Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers’ Parties) was established in 1947 as an unofficial successor to the Comintern in Europe, but it was dissolved by Khrushchev in 1956. In an attempt to revive the international coordination of the movement, several meetings were organized in the late 1950s, culminating in the “1960 International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties”, with 81 parties convening in Moscow. They there developed the rather nebulous concept of the “national democratic state” to capture the complex processes unfolding in many newly liberated states. As the “1960 Declaration” described it:

“The urgent tasks of national rebirth facing the countries that have shaken off the colonial yoke cannot be effectively accomplished unless a determined struggle is waged against imperialism and the remnants of feudalism by all the patriotic forces of the nations united in a single national-democratic front. The national democratic tasks – on the basis of which the progressive forces of the nation can and do unite in the countries which have won their freedom – are: the consolidation of political independence, the carrying out of agrarian reforms in the interest of the peasantry, elimination of the survivals of feudalism, the uprooting of imperialist economic domination, the restriction of foreign monopolies and their expulsion from the national economy, the creation and development of a national industry, improvement of the living standard, the democratization of social life, the pursuance of an independent and peaceful foreign policy, and the development of economic and cultural co-operation with the socialist and other friendly countries.”12“Moscow Declaration” (1960). https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/sino-soviet-split/other/1960statement.htm

As the communist movement understood it, the US-RDA had set Mali on a path of “non-capitalist development”, which entailed an anti-imperialist transformation and thorough democratization of society. An initial phase of “national democracy”13The concept of “national democracy” is similar to the concept of “peoples’ democracy” and what Mao described as “a new-democratic state under the joint dictatorship of several anti-imperialist classes” in his 1940 text On New Democracy.would be necessary in most liberated countries, for decades of colonial maldevelopment had made an immediate socialist revolution impossible. Since the working class was still numerically weak in these countries, this endeavor could not be led by the dictatorship of the proletariat, but rather a transitional form of political organization: an anti-imperialist front consisting of workers, peasants, the petty-bourgeoisie and even elements of the national bourgeoisie.14 (quote)In 1973, DDR-scholars E. Dummer and E. Langer identified the basic prerequisite of such state power: “A decisive criterion for these countries, where the power relations are not yet clearly defined in class terms, where not only social but also political relations are in transition, is that the domestic bourgeoisie has lost the monopoly of political power.” (in Internationale Arbeiterbewegung und revolutionärer Kampf (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1973), 357.) At the helm were often “revolutionary democrats”, members of the intelligentsia or military officers who came to embody the national movement. They were exemplified by figures such as Modibo Keïta in Mali, Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, and Abdel Nasser in Egypt. While maintaining the necessity of this cross-class alliance, the communists also recognized its precarious nature:

“In present conditions, the national bourgeoisie of the colonial and dependent countries unconnected with imperialist circles, is objectively interested in the principal tasks of anti-imperialist, anti-feudal revolution, and therefore retains the capacity of participating in the revolutionary struggle against imperialism and feudalism. In that sense it is progressive. But it is unstable; though progressive, it is inclined to compromise with imperialism and feudalism. Owing to its dual nature, the extent to which the national bourgeoisie participates in revolution differs from country to country. This depends on concrete conditions, on changes in the relationship of class forces, on the sharpness of the contradictions between imperialism, feudalism, and the people, and on the depth of the contradictions between imperialism, feudalism, and the national bourgeoisie.”15“Moscow Declaration” (1960).

It was also asserted that the assistance of the socialist camp could enable these national democratic regimes to create the political, material and socio-economic pre-conditions for socialism without having to pass through a capitalist stage of development.16It was said that the path of non-capitalist development initiated by national democracies would create the conditions upon which a working class – the political subject capable of socialist construction – could emerge. National democratic regimes could thus complete the historical task of the capitalist mode of production without having to endure the agonies of the dictatorship of the bourgeoise. As shown further below, this concept had its roots in the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in 1920 and was expanded after the Second World War to become a cornerstone of communist strategy. See also “sozialistische Orientierung” in Wörterbuch des Wissenschaftlichen Kommunismus (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1982). A key point of reference for the concept of “non-capitalist development” was the Mongolian People’s Republic and the Central Asian Soviet Republics, which had gone through initial periods of revolutionary-democratic transformation in the 1920s and 30s before progressing to socialist construction.17See, for example, Kurt Huber, „Die Mongolische Voksrepublik – Beispiel eines erfolgreichen nichtkapitalistischen Entwicklungsweges zum Sozialismus“ (The Mongolian People’s Republic — An Example of a Successful Non-Capitalist Developmental Path to Socialism) in Nichtkapitalistischer Entwicklungsweg Aktuelle Probleme in Theorie und Praxis (Protokoll einer Konferenz) (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1973). In the former colonies of Africa, Asia and Latin America, this non-capitalist path would mean a continuous struggle against imperialism and, at the same time, a limitation and gradual roll-back of domestic capitalist relations. The aim was to drive the anti-imperialist national revolution towards a socialist revolution, as had happened in Cuba, where the revolutionary democrat Fidel Castro embraced Marxism-Leninism as the revolution advanced. This was theoretical foundation upon which the USSR and its allies set out to support states like Mali in the 1960s:

“The Communist Parties are working actively for a consistent completion of the anti-imperialist, anti-feudal, democratic revolution, for the establishment of national democracies, for a radical improvement in the living standard of the people. They support those actions of national governments leading to the consolidation of the gains achieved and undermining the imperialists’ positions.”18“Moscow Declaration” (1960).

Mali’s path of non-capitalist development and the DDR’s solidarity

Immediately following independence, Mali established close relations with numerous socialist states and sought their assistance in realizing the option socialiste. An initial exchange with East Germany began through the Free German Trade Union Federation (FDGB), which sent a delegation to West Africa in 1960. Malian officials emphasized the need to develop the country’s health care system, since France had left it in a deplorable state. There was an acute shortage of doctors (1 physician per 40,000 inhabitants in 1960), which meant that many illnesses went untreated. Epidemics of tuberculosis, malaria and syphilis were spreading uncontrollably.19DQ 1_23938. After Mali’s minister of health expressed interest in cooperating in this field, US-RDA representatives travelled to the DDR to develop plans. The focus of the cooperation was to be on preventive care for the population and reorganizing the structure of the health system. 60,000 polio vaccines were soon dispatched to Mali and the FDGB helped to merge Mali’s health care unions into a more efficient, centralized organisation. A programme was also developed to train Malian students in East Germany. The first class arrived at the medical school in the town of Quedlinburg in 1960. They were followed by hundreds of other Malians that would study a variety of fields. Cooperation was then gradually expanded to include skilled worker training, cultural exchanges, popular education partnerships, and political cadre schooling.

Agricultural production was the central economic activity in Mali, with 90% of the working population engaged in this sector. It was also the country’s primary source of accumulation, with 92% of exports coming from agriculture. Yet in many regions, the level of productive forces remained extremely low: the land was worked by families who used hand-operated implements and consumed more than three quarters of their yield for subsistence. Since the particularities of colonial rule in French Soudan had not given rise to large private estates, there was no need for a land reform similar to those in Cuba, Egypt, and Iraq. Instead, the action rurale sought to transform the semi-communalist villages into cooperatives (Groupement Rural de Production et de Secours Mutuel, GRPSM) and connect them to state-run facilities (encadrement rural) that would assist famers in the use of modern production methods. The action was to be the centrepiece of socialist transformation in Mali; the aim was to boost agricultural production beyond subsistence farming and, through state-run trading companies, generate the funds necessary for industrialization. The GRPSM were also to become engines for social progress in the countryside: they were to elect their own management structures and establish literacy centres, sanitary stations, shops, and seasonal schools for young villagers.

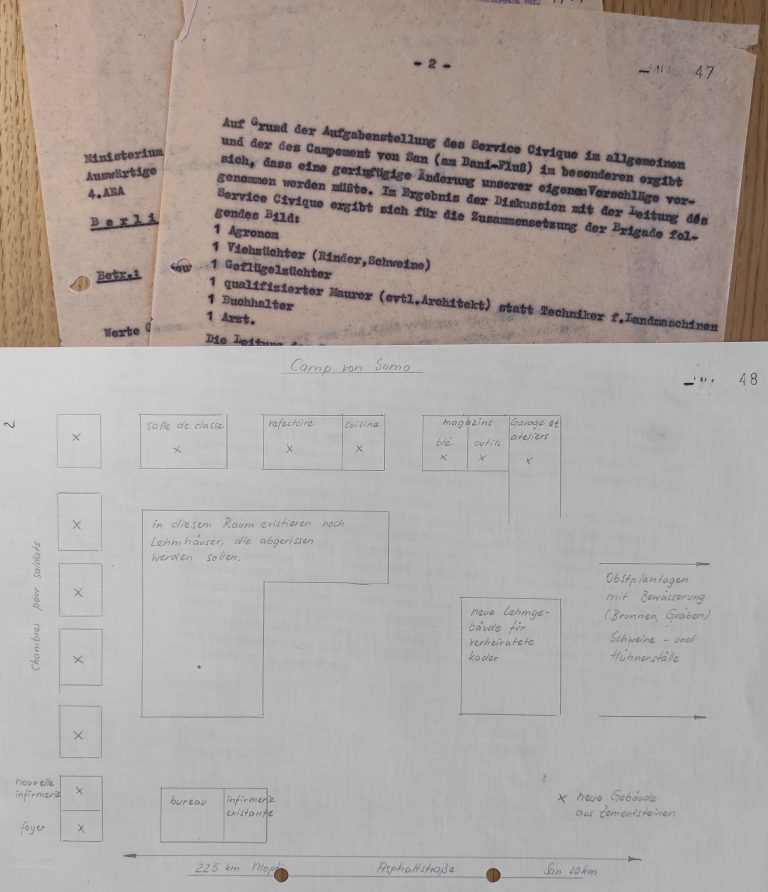

After a request for assistance from JUS-RDA, the mass youth movement of the DDR, the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ), kitted up a “Friendship Brigade” in 1960 – the first of what would become dozens of brigades sent throughout the world – to assist in the construction of a GRPSM in Somo, Mali. The first brigade consisted of six members: an agronomist, a cattle farmer, a mason, a carpenter, a mechanic, and a doctor. Their gear included a tractor and plough, a truck and trailer, a seed sowing machine, a jeep, and a centrifugal pump. The brigade worked alongside 30 Malian farmers, sowing rice, millet, and peanuts, and constructed new buildings for cattle breeding and maintenance work.

By the mid 1960s, significant gains had been made in Mali, especially in comparison to the decades of colonial rule. While the French had only spent 4% of colonial taxes on education in West Africa, the US-RDA had managed to double the number of primary and secondary students in just 3 years.20Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Argumente und Tatsachen, Zur Entwicklung der afrikanischen Parteien. Hundreds of new medical facilities and sanitary stations had been constructed throughout the country. In agriculture, over 45,000 hectares of land were irrigated, and 30,000 ploughs had been delivered to the GRPSM, while the construction of the encadrement system and seasonal schools had been mostly completed by the end of 1965.21Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf.

Yet these gains fell short of the US-RDA’s ambitious five-year plan. While cotton, corn and peanut production expanded, the production of subsistence crops stagnated (rice) or even declined (millet).22Ibid. The action struggled with several practical and political challenges. The more radical wing of the US-RDA had envisioned a gradual transformation of the subsistence-based villages into modern commodity-producing cooperatives that, when integrated into a wider system of state planning, could fund industrial development on a national scale. Right-wing and centrist elements in the party, however, advocated for a revival of “traditional” village structures that had been deformed by colonialism. Echoing the ideas of other agrarian socialist movements such as the Narodniks in 19th century Russia, this tendency idealized the semi-communalist methods from the pre-colonial era. They advocated for a rehabilitation of “traditional values and norms” to reawaken farmers’ “inner need for progress”, reducing socialist transformation in the countryside to a kind of “psychological revolution” amongst the villagers.23Colloque sur les politiques de développement et les diverses voies africaines vers le socialism (Dakar: 1962), cited in Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf, 45. As a result of these divergent conceptions within the party, the action rurale was inconsistently implemented at the local level.24Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf, 109–113. While novel democratic decision-making structures were erected in some villages, officials in other regions sought to merely “de-colonise” the villages, which inadvertently strengthened or sometimes even revived patriarchal relations and the quasi-feudal aristocracy from the pre-colonial period – the very forces most reluctant to the idea of socialist transformation.

The most significant problems crippling the Malian economy, however, were of external origin. The US-RDA had been able to drive out foreign corporations from the domestic agricultural market and thus stop the direct outflow of Mali’s national product, but Malian commodities were still at the mercy of prices on the capitalist world market. The cost of transporting goods across national borders to ports in Senegal and Guinea, as well as the subsidy schemes for cotton in Europe and the United States, made it almost impossible to make a return. Unequal exchange embodied “the hidden hand of neocolonialism” (Nkrumah) in Mali. Yet France was brazen enough to also employ a more visible hand, interfering with petrol deliveries and pressuring the Senegalese government to create obstacles on the transit routes to Dakar.25This information was passed along to a DDR delegation by President Keïta and Mahamane Alassane Haïdara (the president of the National Assembly) in May 1966 (DY 30/98103). As the terms of trade deteriorated year after year, Mali’s deficit began to balloon, and local merchants started enriching themselves by bypassing the state trading company and smuggling goods across the Senegalese border. After failing to effectively combat this growing black market, Keïta’s government resorted to wage cuts and price increases in 1965.

As economic problems mounted in the mid-1960s, Keïta repeatedly approached the socialist states to ask for more assistance. Yet despite numerous efforts, the DDR failed to establish commercial ties with Mali, citing “the narrowness of Mali’s export structure and Malian price demands above the world market price”.26DY 30/98102. In terms of material assistance, the Soviet Union had been able to provide Mali with credit worth some 68 million USD between 1960 and 1967. Together with the ČSSR, the Soviets had focused on training programmes for Malian professionals and cadres, prospecting for minerals, and expanding aviation.27Helmut Strizek, “Mali zwischen Moskau und Peking — vor und nach dem „Sozialismus“” (Mali between Moscow and Beijing — before and after “socialism”), Osteuropa 26, no. 4 (April 1976) and DY 30/98101. By the end of 1968, China had also lent Mali some 30 million USD and sent hundreds of experts to train Malian students, with an emphasis on agricultural schooling.28 (quote)Although Western analysts tend to emphasize tensions between Soviet and Chinese activities in Africa during this period, internal SED and the ministry for foreign affairs (MfAA) reports do not devote much attention to the issue. The CPC’s influence on the US-RDA was observed by DDR representatives in Mali, but their findings only appear as side notes in reports focused on broader political or economic developments. In fact, the head of the DDR’s trade mission in Bamako explicitly downplayed the threat posed by “ultra-left forces” (i.e., Maoists) in September 1967, arguing that “the main threat to Mali’s progressive development is currently posed by the right-wing forces. Assessing things differently would amount to turning the current situation on its head.” (DY 30/98101) Yet what Mali urgently needed was strong trading partners that could purchase goods at prices above those on the imperialist world market. Without a steady stream of revenue from agricultural exports, the option socialiste would be doomed to failure.29By 1964–65, the socialist states were importing some 43 percent of Malian exports, but they were simply not in a position to replace Mali’s ties with its former colonizer and the economically stronger EEC. M. Touron, “Le Mali, 1960–1968. Exporter la Guerre froide dans le pré carré français”, Bulletin de l’Institut Pierre Renouvin 2017/1, no. 45 (2017).

The situation in Mali became acutely tense in February 1966 after a counterrevolutionary putsch toppled Nkrumah’s socialist-oriented government in Ghana. Aware of the dangers posed by domestic instability, Mali’s national assembly agreed to grant extraordinary powers to a Comité National de Défense de la Révolution one month later.

Questions of political organization – a popular front or a vanguard party?

Internal divisions within the US-RDA intensified as the economic situation deteriorated. The right wing of the party, resting largely on the ascendant merchant class and the administrative bureaucracy, went on the offensive and began negotiating a financial agreement with France to bring about the re-entry of Mali into the CFA franc zone. The proponents claimed the agreement would help stimulate trade with neighbouring countries, but opponents argued it represented the end of the option socialiste, for it would erode the state’s control over trade and give France a dominant role in the economy. Driven by the youth in the JUS-RDA and the workers in the UNTM, the left wing of the party blamed corrupt officials and their half-hearted implementation of revolutionary policies for the economic crisis. They began calling for the development of a vanguard party, which – with stricter discipline and greater unity of action – would be better suited for the hostile environment.30Internal strife within the party leadership was detailed to East German officials by several US-RDA politburo members who travelled to Berlin for the SED’s 7th Party Congress in April 1967 (DY 30/98100).

In the mid-1960s, against the background of similar challenges across the continent, the question of vanguardism became a point of dissension amongst communist and progressive forces in Africa. A conference entitled “Africa – national and social revolution” was organized by the theoretical journal Problems of Peace and Socialism (commonly known as World Marxist Review) and the Egyptian periodical Al Tali’a in late October 1966. Politicians and theoreticians from 25 African parties and organizations gathered in Cairo to discuss the situation confronting anti-imperialist forces in Africa. Of central concern was the military putsch in Ghana just eight months prior. Lutfi Al Kholi, one of the chief editors of Al Tali’a, highlighted how British-trained officers in the Ghanian military had exploited the country’s economic instability and acted on behalf of the imperialist powers.31Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus (Problems of Peace and Socialism), iss. 01, 1967. He argued, however, that it would be “self-delusion” to “imagine that imperialist intrigue alone was the main cause of the coup”. Nkrumah’s governing party, he said, had ultimately been unable to organize resistance because it “remained a ship floating on the surface of society, comprising a group of revolutionary intellectuals and town-dwellers” that “failed to reach out to the mass of the people in the countryside, to enlighten and rally the masses generally, to really arise their interest in the revolution.” Tigani Babiker of the Sudanese Communist Party agreed: “Confused and unorganized masses could not face and defeat an armed coup by themselves. That would have required a militant revolutionary vanguard party.”32Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, iss. 01, 1967. Such a party would be better suited to “provide a solid basis for political stability by ensuring a close bond between progressive governments and the people,” during non-capitalist development, as the Senegalese Marxist Thierno Amath argued.33PFS, 1966, iss. 08

The Malian representative in Cairo was Idrissa Diarra, the then political secretary of the US-RDA and principal leader of the party’s right wing. Diarra disagreed with those in his party and at the conference who were maintained the necessity of a vanguard party during the second stage of national liberation. In his view, the specific historical development of Africa meant that anti-imperialist popular fronts were capable of constructing socialism on the continent.34Idrissa Diarra in Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, iss. 01, 1967. He argued that no major class-based parties had emerged in Africa at the end of the colonial era because, firstly, foreign exploitation had stunted the process of class differentiation and, secondly, all social groups were united in their contradiction to imperialism. Thus, mass parties representing cross-class fronts came to lead the anti-colonial struggle.

“By the end of colonial rule, the situation had become more favorable for social differentiation, but it would be wrong to claim that society is already divided into antagonistic classes. Contradictions and social distinctions are not sufficiently pronounced to do away with the general sense of solidarity that unites the members of African society.”

While those African states that had chosen to encourage “foreign and national private capital” were inadvertently aggravating class contradictions and thus making the emergence of a vanguard party inevitable, Diarra argued that the national democratic states pursuing socialist construction were already “overcoming the basic contradictions” in society.

“Socialisation of the means of production and circulation has increased the number of people employed in the state sector, who are the natural supporters and defenders of the party’s socialist orientation. While socialist orientation was initially based mainly on volitional factors, later structural changes in the field of the economy broadened more and more the objective basis of the struggle for socialist development. Parallel to this, the objective basis of the forces opposing the socialist orientation of the party is becoming narrower.” 35 (quote)Four years earlier, S. B. Kouyaté from the US-RDA leadership had made similar remarks: “In summary, we can say that the socialist road we have chosen is based on two fundamental points: 1) a socialism established by a movement, not led by mainly proletarian forces … 2) and as a logical consequence of the first point, we think that socialism can be realised without a communist party. We think that the political organisation of the people, considered as the motor of the nation, can lead the country to socialism.” Quoted in Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf, 32.

Diarra’s position was controversial, both within his own party and within the international movement. When a delegation of left-wing US-RDA politburo members travelled to Berlin several months later in April 1967, they explained to SED officials that the party was split on the vanguard question. They described Diarra’s contribution at the Cairo conference as “a reflection of his personal views, not those of the politburo”.36DY 30/98100. They reported, however, that many members feared the creation of a vanguard party would compromise “the unity of the country” and alienate some of those who had fought for independence. The left wing thus preferred to strengthen “the vanguard forces inside the party” in order to “further develop the party from within.”

While the socialist camp refrained from taking a public position on these organisational questions in West African mass parties at the time, Diarra’s views clearly contradicted the Marxist-Leninist understanding of national liberation and socialism, for they “overestimated the potential of a national-democratic mass party and its petty-bourgeois leadership” while simultaneously “underestimating social differentiation and class struggle”.37Note, this assessment of Diarra and Kouyaté’s views was written by Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf, in 1973, five years after the coup against the US-RDA. The Guyanese Marxist Walter Rodney had identified the same problem in a number of African mass parties at this time.38Walter Rodney, Decolonial Marxism, (London: Verso Books, 2022), 47–49, 68–69, 284–285. For the communists, class struggle would necessarily intensify during the second stage of national liberation, and it would be up to the working class to achieve hegemony in the national movement.39 (quote)As the leading Soviet theoretician R.A. Uljanowski wrote in 1970: “How the transformation of the national democratic parties into parties of scientific socialism will take place, how and when the Marxist-Leninist parties will emerge where they do not exist — to speak of this would be premature. What is indisputable is merely that the gradual turning away from capitalism in the process of the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggle can be initiated in the national-democratic stage of the revolution under the leadership of revolutionary democracy, but the successful conclusion of this process and the transition to socialist construction and later the guarantee of the full victory of socialism are impossible without the party of scientific socialism, without the leadership of the working class.” in Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, 1970, iss. 06. This is essentially the same conclusion that Rodney (2022) reaches. Nkrumah came to a similar conclusion upon critical reflection in his 1970 book Class Struggle in Africa.40 (quote)“The rash of military coups in Africa reveals the lack of socialist revolutionary organisation, the need for the creation of an all-African vanguard working-class party, and for the creation of an all-African peoples’ army and militia. Socialist revolutionary struggle, whether in the form of political, economic or military action, can only be ultimately effect if it is organised, and if it has its roots in the class struggle of workers and peasants.” Kwame Nkrumah, Class Struggle in Africa (London: Panaf Books, 1970), 54.

Despite this ideological divergence, the socialist states continued to support parties like the US-RDA. Openly criticizing these tendencies would have undermined progressive governments in Africa and besides, it was held that the dynamics of the national-democratic process would necessarily give rise to Leninist parties capable of socialist construction, as had happened in Cuba. In early 1967, the SED concluded that future cooperation should pay special attention to strengthening “progressive forces within the US-RDA”, thereby helping to consolidate “Mali’s non-capitalist path of development”.41DY 30/98100. The cadre training programmes already underway in the USSR, the ČSSR, and Bulgaria were to be expanded to include Mongolia and the construction of a party school for the US-RDA in Bamako.

The “revolution active” and the November coup

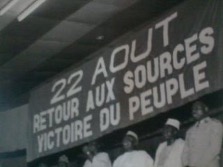

The financial deal with France was provisionally agreed to in February 1967. The first stage of its implementation followed shortly thereafter, and this proved fatal for Mali’s already unstable economy. In the subsequent three months, the value of the Malian currency dropped by 50 percent.42This figure is provided in DY 30/98105 and verified in Pierre Boilley, Encyclopedia of African History, Routledge, 2013. Unrest began to shake the cities as large demonstrations called for action against the “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” that had emerged in the state apparatus. The JUS-RDA, partially inspired by the Chinese cultural revolution, launched operations to combat corrupt government officials and renew the party. The events culminated on 22 August 1967, when Keïta announced the “revolution active”: the politburo of the US-RDA was dissolved and the Comité National de Défense de la Révolution (CNDR) assumed its responsibilities. The National Assembly dissolved itself five months later in January 1968 and was replaced by a provisional assembly of left-wing figures.43These developments were closely observed by the head of the DDR’s trade mission in Bamako, who sent detailed monthly reports to the MfAA in Berlin (DY 30/98101 and DY 30/98105). Idrissa Diarra and his allies were thereby purged from the leadership, yet many lower-level party and state positions were still held by the bureaucratic bourgeoisie.

Madeira Keita, who was Mali’s minister for justice, came to lead the progressive forces in the CNDR. In July 1968, Keita delivered a pivotal address in which he analyzed the development of Mali since 1960.44The speech is detailed in an internal report from the trade mission to the MfAA (DY 30/98105). He repudiated the position presented by Diarra in Cairo and argued that antagonistic social forces had in fact emerged following Mali’s independence. The “opposing political objectives” of these groups, he said, had led to a political crisis in 1966/67. With the help of “mass actions by the youth and unions”, progressive forces have been able to regain the initiative and avert a right-wing putsch, but this danger still looms over Mali. The left wing of the party has come to the realization that it is necessary “to transform the US-RDA and the state apparatus from within, from organs which include all social strata, to institutions of the vanguard forces.” The dissolution of the politburo and national assembly marked the beginning of this process, but it was far from complete. Keita concluded by reiterating the urgency of boosting agricultural productivity and warned that the party had underestimated the “rigidity of old African traditions” in the villages. In the same vein, a seminar on the action rurale held in May 1968 had concluded that the “patriarchal gerontocracy” and “theocratic feudal elements” in the villages had been greatly underestimated, while the revolutionary potential of exploited groups (the poorer families, the youth, and the women) had been insufficiently drawn upon.45Cited in Ernst, Tradition und Fortschritt im afrikanischen Dorf.

This leftward shift in the US-RDA was also discernable in the government’s foreign policy. In March 1968, Mali’s minister of commerce travelled to Berlin and informed SED officials that “the time is ripe to move towards normalisation of relations and full diplomatic recognition of the DDR”.46DY 30/98102. This was a development that the DDR had long pushed for, but had made little progress on in light of Mali’s hesitancy to lose ties with West Germany, who threatened to cut off relations with any state that recognizes the DDR (see the Hallstein Doctrine). While the US-RDA representatives said that Mali was now prepared to take this step, they emphasized that the socialist states would have to step up their assistance if non-capitalist development was to succeed. When President Keïta met with the head of the DDR’s trade mission in Bamako in July 1968, he lamented the financial agreement with France, describing it as a bitter retreat made necessary by the socialist states’ failure to provide sufficient support.47DY 30/98102. Yet, despite his continued frustration with the socialist camp, Keïta unequivocally positioned himself a month later when, in August 1968, Mali became the only African state to explicitly support the USSR’s intervention in the ČSSR.48Mali’s declaration of support was approved by the CNDR and separately by the trade unionists in the UNTM (DY 30/98105). Madeira Keita had visited the DDR and the ČSSR in July/August of that year and thus understood the situation in Prague well. The significance of this move should not be underestimated, for the US-RDA positioned itself as a close ally of the Warsaw Treaty states and contradicted the position of its allies in China, Yugoslavia, the PCF, and several progressive states in Africa. In defiance of its allies in Yugoslavia and Egypt, the US-RDA then refused to attend the next conference of the Non-Aligned Movement.

The revolution active was in essence what the communist movement had been anticipating; contradictions within and around the US-RDA had forced it to adopt a clearer ideological position. The remaining leaders abandoned talk of the “unity of the country” and were now railing against the “reactionary forces who had links with capitalist foreign countries”.49DY 30/98103. They turned to the workers’ and youth movement for support. A popular militia was granted special powers over all other organs of power to repel the counterrevolution.50Interestingly, the UNTM even reached out to the SED to ask for help organising armed worker brigades modelled on the DDR’s “Combat Groups of the Working Class” (DY 30/98103). Outside the urban centers, however, the rural masses were focused on the disastrous economic situation, which showed no signs of improving. Most Malians reportedly appeared apathetic to political developments in the cities.51DY 30/98103. Making matters worse, the popular militia proved prone to excesses, which further alienated some once-time supporters of the US-RDA.

The fatal blow against the party came in late 1968. As in Ghana, the military in Mali had long been a bastion of pro-imperialist attitudes. Many officers had been trained in the colonial “mother country”. While they had tolerated Keïta’s presidency, they favoured closer ties with France. The rise of the popular militia during the revolution active also angered many officers, for they feared the dissolution of the army. After a violent dispute between militia members and army officers on the evening of 18 November 1968, a surprise putsch was launched by a group of officers. The headquarters of the popular militia, the UNTM and the JUS-RDA were swiftly surrounded and neutralized to disorient the pro-government forces. Keïta was arrested alongside his ministers, including Madeira Keita, and Bamako’s radio station began transmitting messages in support of the coup: “Long live individual freedom, long live the Republic. Down with the militia. No more so-called socialism. Long live the army.”52DY 30/98105. The merchants and petty businessmen saw their hour coming and threw their support behind the military. The rural population remained largely passive.

The leader of the conspiring officers – the self-proclaimed “Military Committee for National Liberation” – was Lieutenant Moussa Traoré, who had recently returned to Mali from a long visit to Paris, purportedly for health reasons. While French representatives in Bamako appeared to have been surprised by the November coup, rumors were circulating that the French had long been in contact with several officers, but they had yet to settle on a date for moving against the US-RDA.53DY 30/98105. Following the putsch, Traoré promised new elections in the coming months and, tellingly, the right-wing figures that had negotiated the financial deal with France before being purged from the US-RDA were now reinstated as ministers in the new provisional government. All other political activity – including that of the US-RDA and its mass organisations – was banned altogether. The promised elections never arrived and Traoré held onto power until being ousted in 1991. Modibo Keïta died as a prisoner under suspicious circumstances in 1977, whereafter thousands flocked to the former president’s funeral before being violently dispersed by Traoré’s troops.

A legacy to study

The 1968 coup thus brought Mali’s non-capitalist development to an abrupt end, as had happened in Ghana two years prior. The DDR and other socialist states continued relations with the Traoré regime, mostly in the hope of conserving gains and counteracting the influence of the imperialist states, but there was disagreement as to the prospects for Mali’s future development under military rule.54 (quote)A detailed post-putsch assessment from the East German trade mission director was delivered to the MfAA in January 1969 (DY 30–98105). Interestingly, the FDJ brigade that was on the ground at the time of the putsch was able to deliver a clearer analysis that, with hindsight, proved accurate: “It can be recognised from the first declarations of the representatives of the new state power that with 19.11. a shift to the right has taken place and that this development will continue. It won’t start abruptly, the new people can’t afford that, the idea of socialism is already too deeply rooted. We will probably have to deal with some variety of pseudo-socialism. … What is clear [from Traoure’s economic programme] is that Mali’s door has been opened to foreign capital. Local traders and entrepreneurs were given a ‘green light’.” (DY 30/98102) While some analysts such as C. Mährdel entertained rather vague notions that “the ruling political circle” in Mali may be “treading the path towards revolutionary democracy”, others like the French communist J. Suret-Canale believed that Mali had “once again come under imperialist tutelage”.55C. Mährdel, Afrikanische Parteien im revolutionären Befreiungskampf, (Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1977), 14. And Suret-Canale, “Die Bedeutung der Tradition in den westafrikanischen Gesellschaftsordnungen”, 136. The latter assessment proved correct.

It would be too simple, however, to conclude from such coups that the strategies of non-capitalist development and national democracy were unviable. While the objective and subjective difficulties in Mali proved to be greater than the communist movement and the US-RDA had initially anticipated, there are several states in which these strategies did pave the way for socialism.56For national democracy, the obvious examples are Cuba and China. For non-capitalist development, see Mongolia and the Central Asia Soviet Republics. To understand why, it is helpful to recall the origins of these concepts. Non-capitalist development was first alluded to at the Second World Congress of the Comintern in 1920 and it is clear from this initial remark that the strategy presupposed a strong socialist antipole to imperialism:

“The question was posed as follows: are we to consider as correct the assertion that the capitalist stage of economic development is inevitable for backward nations now on the road to emancipation and among whom a certain advance towards progress is to be seen since the war? We replied in the negative. If the victorious revolutionary proletariat conducts systematic propaganda among them, and the Soviet governments come to their aid with all the means at their disposal – in that event it will be mistaken to assume that the backward peoples must inevitably go through the capitalist stage of development. Not only should we create independent contingents of fighters and party organisations in the colonies and the backward countries, not only at once launch propaganda for the organisation of peasants’ Soviets and strive to adapt them to the pre-capitalist conditions, but the Communist International should advance the proposition, with the appropriate theoretical grounding, that with the aid of the proletariat of the advanced countries, backward countries can go over to the Soviet system and, through certain stages of development, to communism, without having to pass through the capitalist stage.”57Lenin (1920), “Report Of The Commission On The National and The Colonial Questions” in The Second Congress Of The Communist International. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/jul/x03.htm (Emphasis added)

This premise was then taken up by revolutionary forces in the newly liberated states, as Madeira Keita wrote in 1967:

“The knowledge that the Soviet Union and the socialist camp exist in the world and that we can depend on their solidarity, helped us to understand the Marxist proposition that newly independent nations lacking an industry, an infrastructure, national personnel and a developed national bourgeoisie, can bypass the stage of development in which a bourgeoisie emerges and takes power. That is why we opted for the path of socialist development.“58See Madera Keita in Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, 1967, iss. 11

The tragedy of developments in Mali, however, was that despite positive political developments within the US-RDA (represented most clearly by Madeira Keita himself), the socialist camp was ultimately unable to establish economic ties with Bamako to an extent that could free it from neocolonial dependencies. This was greatly hindered by the fact that the pan-African initiatives of the early 1960s had failed; the region remained balkanized, and Mali was left relatively isolated. By 1965, it was clear that, so long as the landlocked Mali was subject to prices on the imperialist world market, the country would not be able to maintain a stable trade balance, let alone accumulate the capital necessary for industrialization. The fact that the DDR – arguably the most economically developed of the socialist states – never managed to establish meaningful trade with Bamako should have raised more concern than it did. Solidarity projects and training programmes were undoubtably important, but what Mali required was a stable stream of revenue. Despite recurring pleas from US-RDA leaders, Berlin was simply not in a position to pay over and above market prices for Malian agricultural goods. The DDR, like the other socialist states, was of course entangled in its own (re)industrialization efforts and fierce competition with the West at the time.

Proponents of non-capitalist development had evidently overestimated the capabilities of the socialist camp after the Second World War, at least in relation to Sub-Saharan Africa. While Soviet assistance had enabled some feudal societies in Central and East Asia to bypass the capitalist stage of development, these states had been directly linked to the Soviet economy. Transposing the idea onto balkanized West Africa was another matter entirely. It would have required a much stronger Comecon (as a socialist alternative to the imperialist world market) or an international infrastructure project capable of linking distant landlocked countries like Mali to the socialist states in Europe and Asia. Communist analysts began to recognize and discuss this point in the 1970s59 (quote)The limitations of the strategy were hinted at, for example, by Suret-Canale (“Die Bedeutung der Tradition in den westafrikanischen Gesellschaftsordnungen” p.136) who identified three basic contradictions that hampered non-capitalist development in Ghana and Mali: “The continuance of neo-colonialist influence in neighbouring states, the relative isolation of progressive regimes and the geographical distance from socialist countries.” Similarly, Nigerian communist Tunji Otegbeye concluded in 1970 that the “proximity of [the newly liberated states] to the world socialist camp” was a major economic and political factor determining their “transition to the socialist orientation,” (Probleme des Friedens und des Sozialismus, 1970, iss. 08). Nkrumah, like Otegbeye, concluded that non-capitalist development must be considered as nothing more than a very brief transitionary phase, not an independent social formation (Nkrumah, Class Struggle in Africa, 38–39)., yet non-capitalist development remained a core strategy for the movement until the mid-1980s, before Gorbachev’s “new thinking” set in. Comparing Mali’s experiences with those in other socialist-oriented states such as Guinea, Egypt/UAR, Mozambique, PR Congo, DR Afghanistan, etc., will help to gain a broader understanding of the possibilities and limitations of this concept in the 20th century.

On the political front, the crux of national liberation was how the immediate fight against neocolonialism could be linked to the long-term struggle for socialism. How can national liberation go beyond the bounds of a bourgeoise revolution when the proletariat – the decisive revolutionary subject – is only in an embryonic form? Drawing on Lenin’s Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, the communist parties developed the concept of the national democratic state in 1960. After a decade of praxis, analysts came to appreciate the complexity of this process and recognized that national democracy was inherently volatile; it embodied a constant struggle and was liable to both rapid advances and drastic setbacks:

“In 1960, the world communist movement developed the formula of the national democratic state as the appropriate transitional form for the non-capitalist path of development. The national democratic state is an instrument, but at the same time a reflection of the complicated and contradictory overall social relations. It thus objectively contains a degree of incompleteness, movement, and dynamism – of lower and higher levels of development. In its character, its activity, and its forms and methods of exercising power, there is a concentrated reflection of the degree of class struggle and of the share of power that each class holds. The formula of national democracy as a transitional model is intended to capture precisely this contradictory movement on the basis of class struggle.”60Helmut Mardek, “Der Platz der Arbeiterklasse in den staatstheoretischen Vorstellungen der revolutionären Demokratie“ (The position of the working class in the theory of the state in revolutionary democracy) in Nichtkapitalistischer Entwicklungsweg Aktuelle Probleme in Theorie und Praxis (Protokoll einer Konferenz) (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1973), 184.

In the Malian context, the trajectory of Keïta’s government confirmed the importance of class struggle both outside and inside the national movement. This was evident not only in the question of vanguardism, but also in the action rurale, where idealist conceptions soon began to objectively hinder progress in the countryside.61The action rurale was analysed in depth by DDR scholar Klaus Ernst in his 1973 book, which was translated into English and offers a valuable reference for those interested in non-capitalist approaches to agriculture. As their political projects advanced, revolutionary democrats like Nkrumah and Keïta came to recognize the pitfalls of neglecting a class analysis. In Ghana, this realization came after the coup d’état, but in his final years, Nkrumah warned against class-neutral “myths such as ‘African socialism’ and ‘pragmatic socialism’”62 (quote)“Class divisions in modern African society became blurred to some extent during the pre-independence period, when it seemed there was national unity and all classes joined forces to eject the colonial power. This led some to proclaim that there were no class divisions in Africa, and that the communalism and egalitarianism of traditional African society made any notion of a class struggle out of the question. But the exposure of this fallacy followed quickly after independence, when class cleavages which had been temporarily submerged in the struggle to win political freedom reappeared, often with increased intensity, particularly in those states where the newly independent government embarked on socialist policies.” Nkrumah, Class Struggle in Africa, p.10. In Mali, the US-RDA had learned from the Ghanian putsch and began moving towards Leninism and correcting their policies in 1967 to fend off the aspiring domestic bourgeoisie. Yet here too, the right-wing of the party, in collaboration with neocolonialism, had already inflicted a great deal of damage through the disastrous financial accords with France and the undermining of the action rurale.

In years that followed, a number of parties with sharper class analyses rose to prominence throughout Africa (e.g., the MPLA in Angola, FRELIMO in Mozambique, the PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau, and the PCT in PR Congo). The socialist camp’s role in providing a space for these ideological discussions to unfold – whether in journals such as Problems of Peace and Socialism or in the countless conferences that brought diverse political movements together – cannot be understated. The documentation of these international exchanges offers a wealth of theoretical insights and practical experience that has too often been lost or ignored since 1990.

Today, over 50 years after the putsch against the US-RDA, the people of Mali are still robbed of social progress and economic independence. Life expectancy remains below 60 years, 70 percent of food has to be imported, and only one third of the adult population are literate.63Aged 15 and over – World Bank data for 2020. The deplorable state of the country is a clear indictment of France and its allies who have cast a long shadow over Mali since 1968. Through mechanisms such as the CFA Franc and the IMF’s notorious “structural adjustment programmes”, the dependency and exploitation of West Africa have only been deepened. After ousting the French military in 2022, the Malian people are once again facing the full force of the West’s punitive measures: trade has been embargoed, borders to neighbouring states sealed off, and central bank assets frozen. More than one in three Malians now rely on humanitarian aid for survival.64Press Release January 18, 2022, International Rescue Committee, New sanctions risk plunging the people of Mali further into humanitarian crisis, warn 13 NGOs. This painful perpetuation of neocolonialism stands in stark contrast to the internationalist solidarity of the socialist states. That alone is reason enough to revisit this tradition and pick up these debates anew.