Ulrich Kolbe (*1963), whose parents had served in various foreign assignments for the GDR, grew up in an internationalist household. From 1987 to 1991, he taught German at the “Medifa”, a Medical School in Quedlinburg that specialised in the training of international students, primarily from the national liberation movements or newly independent states. Today he works as a freelance translator, editor, author, photographer, and instructor in California.

As part of our research into the Medifa, we conducted an interview with Kolbe in July 2021. In this first part, he describes the GDR’s anti-imperialist strategy in general and discusses the development of the political consciousness of GDR citizens. In the second part, we talk about the importance of the Medical School itself, both for the students and for the inhabitants of Quedlinburg.

Can you briefly explain how internationalism was understood in the GDR? What was the significance of solidarity?

After 1989, certain concepts were no longer spoken of, they no longer played a role, or they were dismissed. “Proletarian internationalism” was one of them, as was “solidarity” or “peaceful coexistence”. These terms could be heard in at least every other GDR TV news show. They were well known to the people in the GDR. And some of these terms were also put into practice – they became part of people’s lives.

Proletarian internationalism, as we understood it, was based on a simple statement that can also be found in Karl Marx’s Manifesto of the Communist Party: “Workers of the world, unite!” It is something with which nationalism can be countered, namely, to say that people in different countries, with different skin colours, are in fact all the same and they have the same interests. It is about living in peace, about growing up in peace and about health care.

Proletarian internationalism, as it was understood in the GDR, recognized that there were three main currents of the revolutionary world process. First, there was the socialist camp based on mutual assistance, with the Soviet Union at its head. Second, there were the workers’ and communist parties in the capitalist states. Here, too, there was mutual assistance. Of course, many of these parties had a great interest in the GDR’s experience in building a new society. Youth from France, for example, or from West Germany came to the GDR during their summer breaks via youth organisations. Here in the Quedlinburg County, for example, there were partnerships with towns in France that were often governed by communist mayors. They were interested in the GDR and decided to send 40 young people here in the summer. So that was the second current: the communist and workers’ parties in capitalist countries. The third current driving the revolutionary world process according to our understanding were the national liberation movements in the newly liberated or independent countries. Mutual aid took place on these three levels.

I want to underscore that this cooperation was something mutual. It was not the case that the small GDR, with limited economic resources, always just chipped in. Something was also given back – whether it was an exchange of certain experiences, or diplomatic recognition.1West Germany developed the so-called Hallstein Doctrine in the 1950s to impose diplomatic isolation on the GDR. The West German government in Bonn threatened to break off relations with any country that recognised the GDR as a sovereign state. A central task of the GDR on the international stage was therefore to break through this Hallstein Doctrine, which was also achieved towards the end of the 1960s. But it was not primarily about Valuta [i.e., generating convertible or “hard” currency] or anything else, it was really help on a purely human level. That is exactly what proletarian internationalism is. It was about having something to oppose the flag-waving people, no matter if it was for the European Football Championship or the World Cup. We have one flag, and, if anything, it is a red one. It was about standing together for peace, for progress, and for social justice. So that’s the basic definition of what we understood proletarian internationalism to be. Living that was a daily task for everyone and it was practiced differently.

To what extent was this anchored and practiced in the population at large?

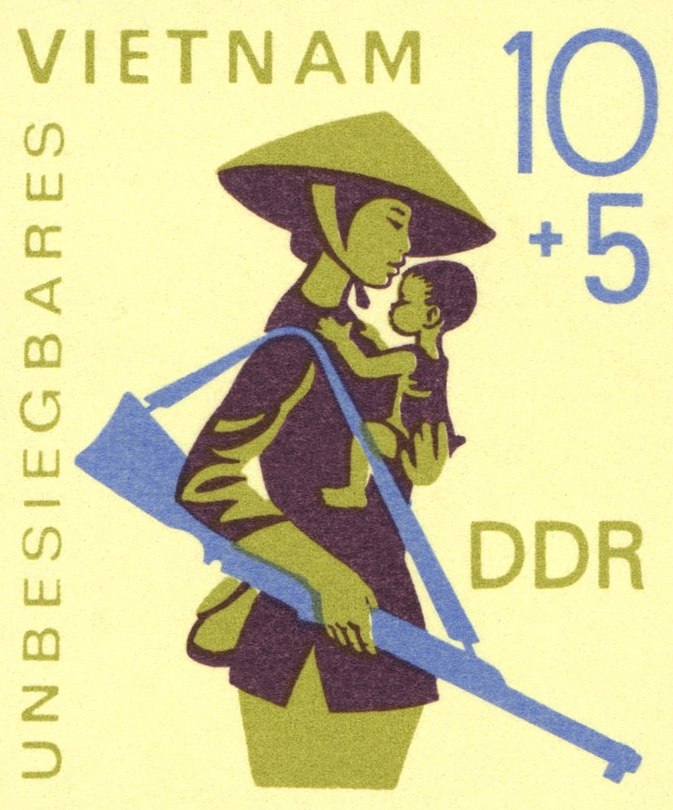

I don’t think it got any easier as the years went by. In the beginning, the circumstances were relatively clear. When a large country like the USA bombed a small one like Vietnam, incinerated it with Agent Orange and mutilated its people, it was relatively easy to convey to the people here in the GDR who we were supporting and why. It was clear that US imperialism, on the one hand, was trying to sabotage the GDR through West Berlin, and, on the other hand, it was bombing this small country in Asia, for which we had great concern. So, there was a very natural connection between the students who came from Vietnam and us. The same was true for the students who came from Palestine or Lebanon because US imperialism was also responsible for the devastating situation in their countries. As a result, people first had the same understanding on this track. This meant that we had an equal understanding with one another.

But I can remember towards the end of the eighties, voices could be heard saying things like, “Back then we sent the Vietnamese our solidarity donations and now we buy clothes from them.” Many Vietnamese contract workers in the GDR sewed jeans at home as a side job. Jeans were not available in our shops, but we could buy them from the Vietnamese workers.

So, towards the end of the GDR, in the late 1980s, the mood somehow changed. There were various reasons for that. One reason was, of course, that it was no longer so easy to differentiate the good guys from the bad guys in the world. For many, of course, internationalism was more than just sticking solidarity stamps in the union membership book every month.2Workers in the GDR could donate towards international solidarity through the Free German Trade Union Federation (FDGB). Upon donation, they would receive a stamp from the FDGB to stick in their union membership book. Many did look for and find other possibilities. For them, the solution was, for example, to meet with foreign citizens, to invite them around and to establish contact with them on a personal level. For many, that was the case, but not for all, of course.

How were GDR citizens informed about developments in the countries fighting for their independence?

We would have to go further and look at the GDR’s very flawed information policy, for which Joachim Herrmann3Editor-in-chief of the Neues Deutschland (New Germany, the SED’s newspaper) and member of the SED’s Politburo. was largely responsible. If you switched on the news show Aktuelle Kamera on evening television, you could expect that the first 10, 15, or sometimes even 20 minutes would show nothing but reports on the public enterprises or “courtiers’ reporting”, as we sarcastically called it. Who did the Chairman of the Council of State receive as foreign guests today? And only after these 20 minutes, the focus finally turned to what was happening in the rest of the world. What is the situation in Chile’s prisons? What progress was the liberation struggle in Angola and Mozambique making? We, who were politically interested, found that infuriating at the time. We felt that the emphasis in the reporting was completely wrong. We saw ourselves as internationalists – the global issues should have come first. They would certainly have elicited the interest of the population at large. But a higher authority didn’t see it that way.

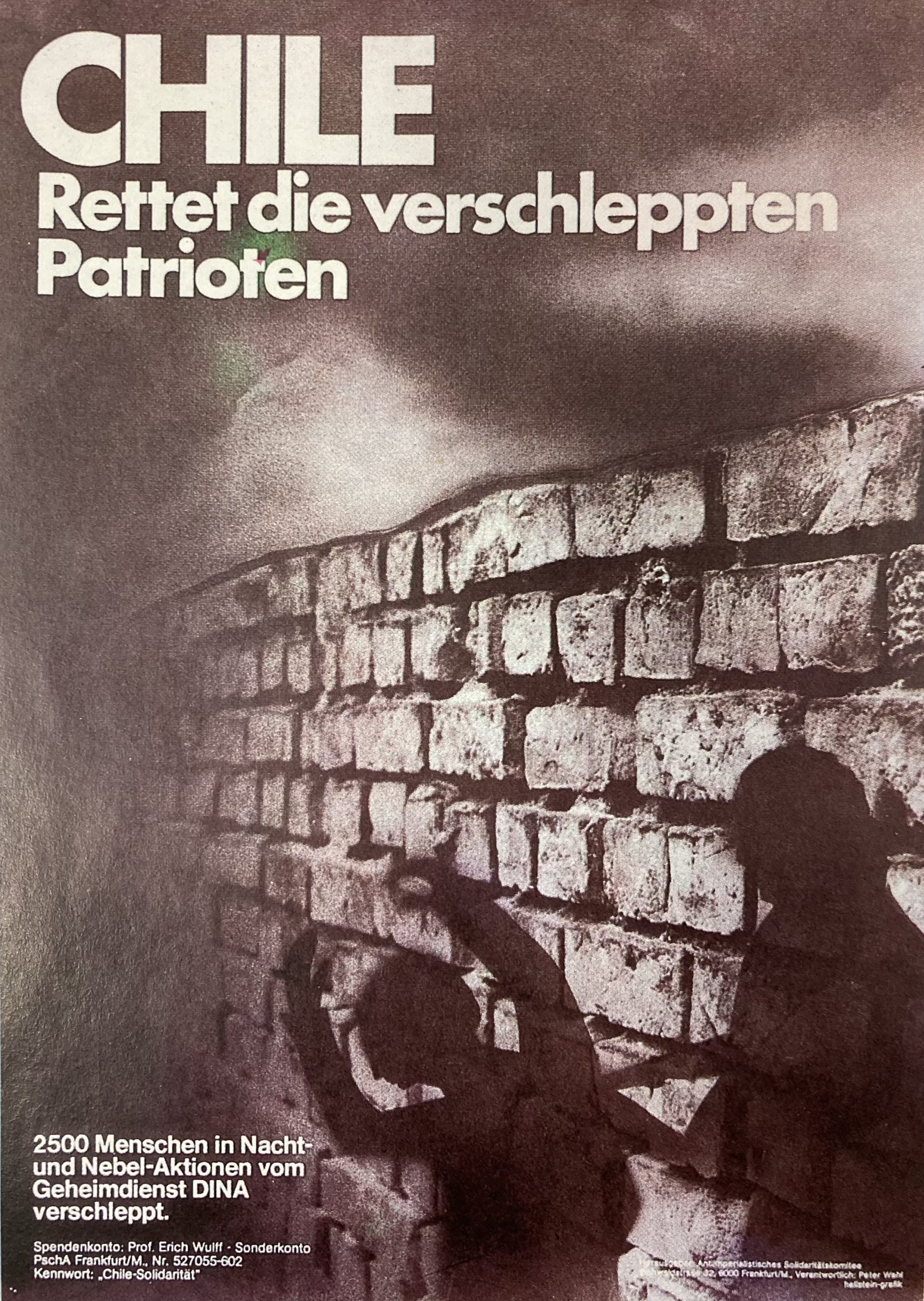

In Quedlinburg, at the Medical College and elsewhere, international events were held to discuss developments in Africa and Asia. In 1973, I still remember, there were countless solidarity events for the patriots of Chile, some of whom escaped to the GDR by the skin of their teeth. After we all celebrated together at the World Festival of Youth and Students in Berlin during the summer of 1973, many of the Chileans that returned home were shortly thereafter driven into Santiago’s stadium, where they were tortured and murdered. We managed to bring quite a few back to the GDR, and you felt a very broad and genuine movement of solidarity at that time. It wasn’t something imposed from above, it wasn’t demanded of us.

I think that at that time, in the 1970s, the majority of the population was still behind these solidarity campaigns and really supported them with heart and soul. The fact that this was later successfully undermined by the West is tragic. At some point, people began to consider their own well-being, their own car, and their own bungalow as somehow more important than what was happening to their comrades in other countries. That is a real shame.

What then distinguishes diplomacy from internationalism, or is one part of the other?

I would certainly say that the foreign policy of the GDR was carried and characterised by the ideals of proletarian internationalism. But now I must bring in another significant concept: peaceful coexistence. This was a concept that one heard every day in the 1970s. It found its expression, for example, in the fact that the Soviet Union and the USA flew a joint space mission in 1975. At the same time, the Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl was travelling with an international crew consisting of researchers from many different countries. In this way, internationalism could also be experienced for us on the screen.

It was not always accompanied by proletarian internationalism, but an interconnectedness, a policy of détente was perceptible. That gave us courage at the time. Foreign policy and internationalism — peaceful coexistence, as we called it, should be maintained and supported everywhere, but not on the ideological front. For example, Marxism-Leninism was not taught as a subject at our Medical College for international students – we were a medical institution, not a political one. But if someone had given political speeches or started movements that ran counter to the aims of this internationalist education, they would certainly have had to be stopped. Because, on the ideological front, there was no peaceful coexistence. That was precisely a principle of proletarian internationalism: vigilance.

Peaceful coexistence with imperialist neighbours – is that not in fact the antithesis of proletarian internationalism?

That’s a good question. On the one hand, our task was also to make socialism attractive as a social model and desirable for people in other countries. In this way, we wanted to prove that we are not like they portray us in movies produced in the west. We are not the snarling communists who eat babies and so on… But it is absolutely true that, from the very beginning, the enemy tried to disrupt our progress and development here by various means. This was most tangible right up to 1961, of course.4The East German border to West Germany, which had hitherto been open, was closed in 1961. And perhaps one of the mistakes in the government’s thinking was the expectation that the capitalist states would roll over the border with tanks at some point and try to end things that way. I think that was still very much ingrained in the thinking of the party and state leadership. Yet the fact that the ideological infiltration – which certainly existed – took place concurrently and was stirred up with very perfidious methods, in large part via West German television, probably could not be circumvented in the end.

Under the conditions of a show down between two social systems completely opposed to each other, I don’t know how things could have been handled better. West German television would have had to be completely banned from the GDR, but that was impossible. So, I suppose you can say that proletarian internationalism was sidelined because peaceful coexistence was at stake. That is true. The flip side of peaceful coexistence was, of course, the costly arms race in the socialist states. The Soviet Union as well as the small GDR had to commit huge resources that could otherwise have gone to other sectors had it not been for this objective need for security.

What can be learned today from the GDR’s experiences?

Yes, this is the central issue: to learn from the lessons of the GDR’s 40-year existence. The internationalism, the internationalist work that was done here was certainly one of the best aspects our small country. When I went to school in the GDR, we learned about the Paris Commune of 1871. The lesson was: don’t give up. There are, of course, setbacks; there always will be.

We felt so sure at the time that this wouldn’t happen to us – we knew the Soviet Union was on our side with its massive, strong military that had been able to defeat Hitler’s fascism. We were far too sure that it could never happen to us, that things could not go backwards for us. And if something did go wrong, we reckoned that any military invasion could have been answered immediately by the Soviet Union’s strength.

Lessons? For me, for the younger GDR generation, it’s probably: don’t give up, keep going. I experienced this myself when talking with the U.S. volunteers who had fought fascism in Spain during the Civil War in the 1930s. These fighters had been defeated by Franco and, after returning home, they were put under surveillance for decades by the FBI. Their passports were confiscated, they were not allowed to travel abroad, simply because they had been politically active. And yet they continued.

You know, in 1990, some people here began putting a big circular yellow sticker from the West German coffee company Tchibo on their briefcases. The slogan on it said, “Oh, fresh beans!” The company Tchibo promised that anyone who visibly carried one of these stickers could win a Mercedes. I reproached these people for having fallen for all that stuff, believing it, and parroting it. “Yeah, sure, everything was terrible in the GDR, and we didn’t have anything. There was constant surveillance by the Stasi and so on…” I really hope that people will start to see these stories for what they are, namely propaganda. And that people realize that life in the GDR – despite all its shortcomings and inadequacies – was much, much better than what it is portrayed as in the media today.

The young generation should learn from the history of internationalism that it can work. So long as we don’t go through the streets waving flags, drunk and believing only in our own country, so long as we recognize that people in other countries have the same interest as we do – to enjoy peace, security, and justice – then internationalism will continue. It must.

The interview was conducted in Quedlinburg on 07.07.2021. It has been slightly edited for better readability.