Nathan Macé

21 May 2024

Introduction

The end of the Second World War inaugurated a new era of the 20th century: the old European colonial powers had been greatly weakened, a new socialist world system had emerged across Asia and Eastern Europe, and the national liberation movements in Africa and Asia were invigorated with a new dynamic. Aspirations for national independence clashed with the fierce colonial apparatus that sought to maintain control over territories, resources, and populations. Yet, in just under twenty years, this hold over Africa and Asia collapsed, culminating in a decade in which a multitude of territories wrested their independence. The factors behind this shift are many and complex, but one in particular interests us in this article: the Groupes d’études communistes (GEC, Communist Study Groups). These organisations are often overlooked in historical accounts of Africa’s independence movements, but they played a role of some importance. French communist historian Jean Suret-Canale, who was directly involved in the GECs during the 1940s-1950s, is the author of a short book on the subject, Les Groupes d’études communistes (G.E.C.) en Afrique Noire, which forms the basis of this article. In his book, Suret-Canale looks back at the GECs, their organisation, membership, and the impact they had in the former French colonies. It is an invaluable account since sources on the subject are very rare. This article examines the experience of the GECs, the colonial context that led to their establishment and the impact they had on the independence and trade union movements in Africa.

Left-wing parties and the French colonial context

“If you do not condemn colonialism, if you do not side with the colonial people, what kind of revolution are you waging?”, declared Nguyen Aï Quoc at the Tours Congress of the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) in 1920. The man who would become famous as Ho Chi Minh was the only representative of the “colonised” in the French colonies. His intervention, at this pivotal event for the French Left, exemplified the attitude of the colonised peoples towards the French Left at the time. The latter – which in 1920 split between the reformist Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière (SFIO) and the revolutionary Section française de l’Internationale communiste (SFIC, later the Parti communiste français) – had a rather ambivalent stance towards the colonies of the French empire.

Indeed, for a long time, SFIO and SFIC policy on the colonies was marked above all by a form of political opportunism and disinterest in the colonial question. While some militants, such as Paul Louis, theorised the need to discuss the fate of the populations of the colonies, many members showed little interest in them, preferring to focus on the fate of the working proletariat in metropolitan France. The first turning point came in 1920, however, when the split at the Tours Congress was triggered by the desire of the majority of the SFIO to join the Third Communist International (Comintern). Political parties seeking to join the Comintern were required to commit themselves to twenty-one conditions: one of which, the eighth, related to the anti-imperialist and national liberation movements in the colonies.

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its “own” country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples.” – Extract from the Terms of Admission into Communist International (July-August 1920)

In the years that followed, the French Communist Party (PCF), as the SFIC was renamed in 1921, embarked on numerous campaigns to oppose and denounce French colonial policy. It opposed the French intervention in the Rif War in 1924 for example, organising strikes with hundreds of thousands of workers to denounce French actions. The Second World War and the rise of fascism in Europe, however, saw the PCF shift its focus away from the colonies once again, as all forces were now concentrated on the fight against the fascists.

GECs in Africa

The origins

While the PCF upheld the fight against French colonialism from metropolitan France, the question soon arose as to how to coordinate this with the struggle of the colonised populations. Indeed, they were the ones suffering directly from French colonial policy. There was in fact a growing number of requests from the colonies seeking to join the PCF. The Party, however, did not want to create local sections of the PCF in the colonies, but rather sought to encourage the emergence of independent parties specific to each territory, built by local cadres with local knowledge. This idea can be found in a letter written by Raymond Barbé, director of the PCF’s colonial section, to Saïfoullaye Diallo, who would later become a minister in independent Guinea. When Diallo had asked to join the PCF, Barbé replied that this would be inadvisable, but this “does not prevent those who wish to do so, because of their sympathy for communist ideas, from grouping together in Communist Study Groups, where they can further their communist education and political training with a view to best serving the orientation and aims of their party”.

During the 1940s, more and more Europeans living in Africa joined “patriotic associations” (such as the Groupement des victimes des lois d’exception de l’AOF, the Groupement d’Action Républicain which became the Front National, the Amis de Combat, France-URSS, etc.), which sought to bring together activists around common themes such as anti-colonial education and resistance to the Vichy colonial regime. While these associations tended to be left-leaning, they consisted exclusively of Europeans (the colonial administration being strictly opposed to any association between natives and Europeans). They thus represented only a small proportion of the population in the colonies. These associations, which gradually disappeared after the Second World War, were an embryonic form of the GECs. It was here that certain militants and organisers met before setting up the first GECs, which gradually replaced the patriotic associations in the more left-wing circles of European society in Africa after 1945.

Although the first GECs began to form unofficially in the early 1940s, it wasn’t until 1945 that a real movement was launched in Africa, notably after the publication of a circular by the PCF secretariat in September 1945, which formalised the desire to create “Groupes d’Études Communistes”. In the same circular, the PCF set out a number of objectives for these organisations: firstly, the GECs should open up to African populations and no longer be limited to a European membership; secondly, the trade unions that already operate in Africa should be united and the separation between European and African unions must be overcome; finally, the ultimate goal should be to create new democratic and progressive political parties that could be the bearers of a liberation movement. The programs of these parties should be inspired by the new program of the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR).1The CNR was the body that coordinated the resistance groups fighting to liberate France from Nazi occupation. Its political program included communist economic inspiration for a plan of social renewal for the liberated country.

The creation of the GECs was thus prompted by several factors: firstly, ongoing requests from African militants to join the PCF; secondly, the presence of patriotic organisations in Africa, which provided a rallying point; and thirdly, theoretical inspiration from Joseph Stalin. On 18 May 1925, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the USSR gave a speech to students at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow, in which he explained the strategy to be adopted in colonised countries where there was practically no proletariat to lead the struggle for independence and revolution.

“We have now at least three categories of colonial and dependent countries. Firstly, countries like Morocco, which have little or no proletariat, and are industrially quite undeveloped. Secondly, countries like China and Egypt, which are under-developed industrially, and have a relatively small proletariat. Thirdly, countries like India, which are capitalistically more or less developed and have a more or less numerous national proletariat.” – Joseph Stalin

According to the PCF’s analysis, many West African countries fall into the first category, as they were essentially agricultural, with no major industry and therefore no real proletariat. Communist militants should therefore set about uniting their forces to create a popular anti-imperialist front.

The GECs were not immediately repressed by the colonial administration: at the time, the communists were one of the leading political forces in mainland France, enjoying great popularity thanks to their role during the resistance to and the liberation from Nazi occupation. The PCF was active in all governments until 1947.

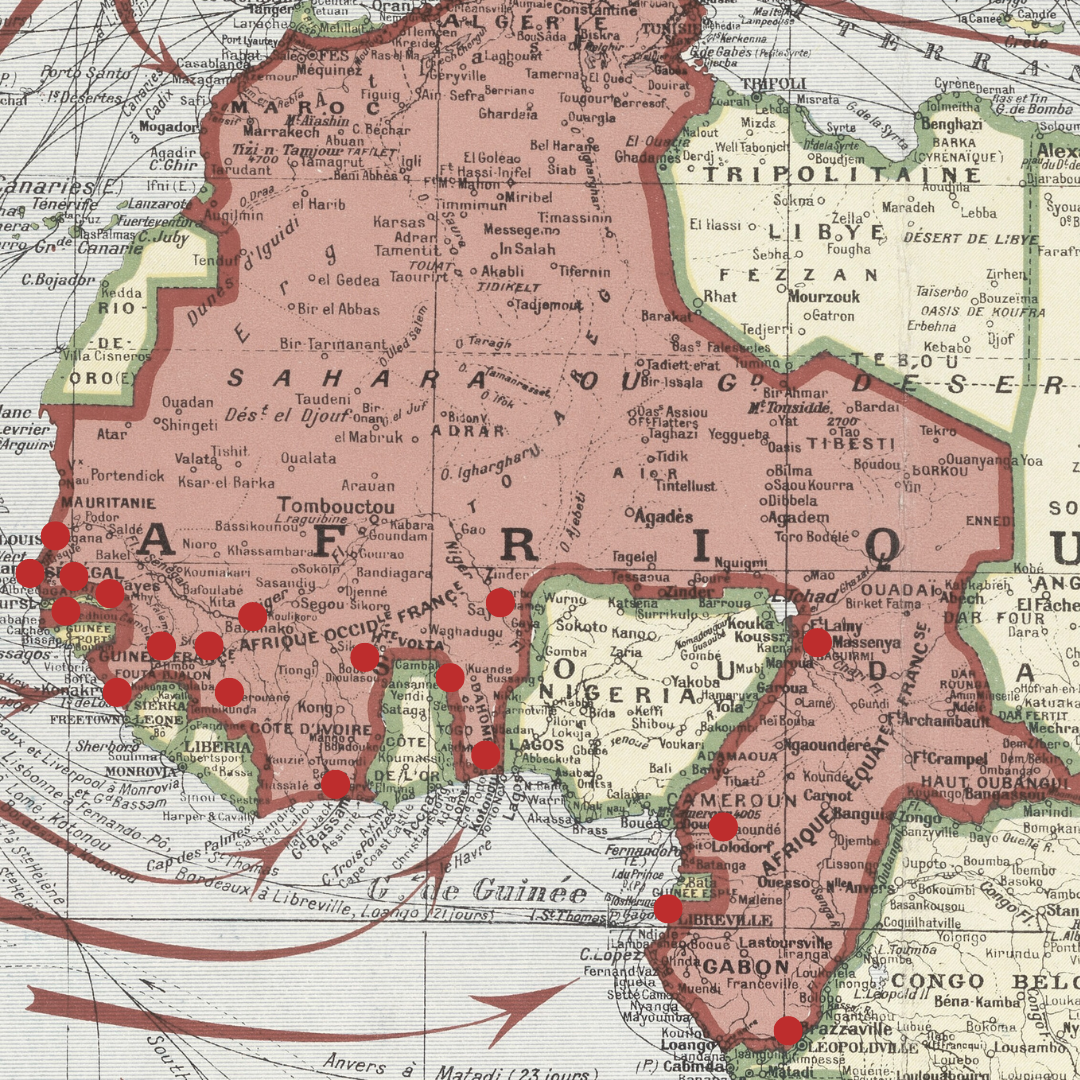

In Africa, GECs began to develop gradually. But, like the patriotic associations, they met with only moderate success at first, and were made up almost entirely of Europeans. Soon, however, African intellectuals began to take up contact with the GECs, and their influence grew. Little by little, more and more African workers joined these organisations, sharing a common distrust of the colonial administration and the actions of the reformist SFIO. Each GEC operated autonomously, only communicating with the secretariat of the PCF’s colonial section and with each other at a regional level. Their activities were manifold: organising political discussion circles, hosting theoretical training sessions, holding evening classes (as with the creation of a Université Populaire Africaine in Dakar), writing and distributing newspapers, organising demonstrations, etc. The GECs also regularly wrote “reports” to the metropolitan headquarters, in which they described the economic and social situation in their region. The GECs were spread throughout the continent: in the Republic of Congo, Senegal, Gabon, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Benin (formerly Dahomey), Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta), and much further afield (Mauritania, Madagascar and even a little in the Pacific).

But the GECs also exhibited flaws and weaknesses. First and foremost, their existence reflected the PCF’s somewhat paternalistic view of African militants, whom it did not consider ready to lead the struggle for independence. This paternalism was illustrated by the fact that the vast majority of GECs had been set up and were for a time run by European militants. As the African independence movements were still in the process of being structured, these cadres provided a certain ‘militant rigour’. The link between the GECs and the PCF’s central structure in metropolitan France was mainly due to the fact that the PCF was the ‘political’ relay in Paris for African demands from the colonies. As the PCF’s central policy shifted towards strong support for independence movements in the colonies, a more important role was given to African militants, who gradually took control of the GECs. Nevertheless, the Groups were ultimately fragile structures, heavily dependent on the most active members running them. As a result, it was not uncommon for certain GECs to go dormant or even disappear altogether if one or two key members left. What is more, after the popular front government in metropolitan France broke down in 1946/47, the colonial administration became increasingly repressive towards these cells of communist political agitation, in which collaboration between Europeans and Africans was increasing.

One example of this repression concerns the Dakar GEC, of which Jean Suret-Canale was a member. In February 1949, when a workers’ strike was organised to demand higher wages, Senegalese Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) union leader Abbas Gueye was prosecuted for leading an “illegal strike”, while Suret-Canale was arrested in the early hours of the morning and deported on the first plane back to metropolitan France. Following a protest movement against these decisions a month later, many activists were arrested, dismissed, and deported. This method of expelling European GEC members to the mainland sought to destabilise the internal organisation of the GECs. While this was often initially effective, it also contributed, almost ironically, to the strengthening of autonomy amongst the African activists, who then took over leadership roles or turned to the new progressive parties.

But the repression against the GECs and against the labour movements more generally also took more violent and dramatic forms. At the end of September 1945, armed settlers fired on strikers demonstrating in the streets of Douala (Cameroon), killing hundreds of people. Following these events, several European members of the Yaoundé GEC were arrested and deported to France, marking the end of the local Group. Local African militants then reconstituted their own GEC in 1948.

The GECs and the Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA)

In October 1946, at a congress held in Bamako (Mali), the Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA) was born as a pan-African federation of major parties on an anti-colonialist basis. Despite many attempts to torpedo the congress (several leading politicians, such as Léopold Sédar Senghor, opposed the event at the behest of their SFIO allies), the delegates were successful at creating the new party, thanks in no small part to the help of the PCF, which hoped the RDA could become the anti-colonial united front it had long been seeking to promote in Africa. Pro-colonial forces did not take kindly to this new anti-imperialist revival. The SFIO, particularly fearful of losing influence in Africa, pursued a divide and conquer tactic by, for example, bribing certain political leaders to oppose the RDA. The PCF’s parliamentary group, meanwhile, grew much closer to the leaders of the pan-African RDA.

“With an appearance of reason, they (the colonists) denounced the fact that we were elected only by a minority of Africans. But it wasn’t us who had established the electoral college. It was the colonists… We therefore asked for the support of a large African movement, a large popular movement that could support our action in the French Parliament, and extend the action that we ourselves had just carried out in diversity… But we had counted without the impetuous of division.…” – Félix Houphouët-Boigny, first president of the RDA

The role of the GECs in this process cannot be underestimated, as many of the big names who took part in the Bamako congress had been members of Marxist groups at the time. Among them were Léon M’Ba (GEC of Libreville, future President of Gabon), François Tombalbaye (GEC of N’Djamena, future President of Chad) and Modibo Keïta (GEC of Bamako, future President of Mali). A few months before the congress, several GEC leaders had visited the PCF headquarters in Paris to discuss the possibility of creating a united front in French Africa. The PCF helped these African militants to draw up a manifesto, which the GECs then used to convince African leaders to join the RDA.

In the years that followed, the GECs continued to maintain links with the RDA, notably through their common membership. But in fact, from 1946 and following the creation of the RDA, the GECs withdrew from local political activism to concentrate on their primary activity: training and educating the next generation of militants. Their links to the PCF and RDA meant, however, that they remained targets of colonial repression. On 13 April 1950, for instance, the US-RDA (the Senegalese section of the RDA) organised an anti-Franco demonstration in front of the Spanish consulate in Dakar. Thirty-eight members of the RDA and GEC were subsequently arrested and seven sentenced to up to six months in prison, or deported to France. Gradually, local RDA sections replaced the various GECs, which had also become more Africanised over time. By the early 1950s, most GECs had been absorbed into the structures of the RDA.

In the face of massive colonial repression and the wave of anti-communism in metropolitan France, the unity in the RDA soon broke down. Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the RDA’s first president who would later become president of Ivory Coast, negotiated with the French government in 1950 to secure a political position for himself in exchange for the eviction of Communist members from the movement. On Houphouët-Boigny’s orders, RDA members in the French National Assembly abandoned the PCF’s parliamentary group to integrate themselves into the government’s Centrist group. This betrayal fractured the base of the RDA throughout Africa, and the ten years that followed were marked by strong repression and the ousting of most communist-minded members. The RDA eventually collapsed completely in 1960, as the new independent parties of Africa struggled to agree on a political line for the Rassemblement and future paths of development for their respective countries.

Conclusion

The Groupes d’Études Communistes were a transient phenomenon in the long anti-colonial struggle of the 20th century. They cannot be understood outside of their historical context. The GECs arose in the final phase of the Second World War, when communists, social democrats, and liberals were still united in the international struggle against fascism. Yet as this anti-fascist front broke down in the second half of the 1940s, the staunch anti-colonialism of the communists came into sharp conflict with the pro-imperialist policies of France’s liberals and social democrats. The colonial apparatus was deployed to divide and destroy the GECs and the wider Pan-African movement.

The scarcity of documentation on the GECs and the hostility towards Soviet-aligned organisations in the Third World has meant that the history of these Groupes has long been overlooked, downplayed or simply written off. However, without ascribing them a role and importance that were not theirs, it must be acknowledged that the GECs had a significant influence on the anti-colonial struggle and the development of political parties in Africa. A scan of the long list of militants who were members of these organisations proves this point: Félix-Roland Moumié, Léon M’Ba, François Tombalbaye, Ruben Um Nyobé, Ousmane and Alassane Ba, Modibo Keïta, Abdoulaye Diallo and many others. These figures, who shaped the political history of Africa and the struggle against colonialism, were at various times active in the GECs.

As described above, some of the most prominent members of the GECs and RDA ultimately betrayed the anti-imperialist struggle in Africa in order to secure power for themselves. This reflected the differentiation process that unfolded in the Third World as the anti-colonial struggle advanced. Domestic classes that had hitherto been united in their opposition to colonialism sought to ensure that their own interests would shape the newly independent states. Yet while figures such as Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast) and Léopold Senghor (Senegal) integrated their countries into France’s neocolonial orbit, others such as Sékou Touré (Guniea) and Modibo Keïta (Mali) led the anti-imperialist social revolution in Africa for many years. The GECs not only rallied together a generation of militants, but also helped to organise trade union forces in Africa such as the Union Générale des Travailleurs d’Afrique Noire, Africa’s largest trade union that was founded in 1957 under the leadership of Sékou Touré. If we bear in mind the three primary objectives set by the PCF in 1945 – greater anchoring of the struggle within the local populations, coordination and unity amongst the trade unions, and creation of progressive anti-colonial parties in Africa – then the GECs can be considered as rather successful.

In order to learn more from the valuable experiences of building and sustaining the GECs, it will be necessary to carry out a more in-depth examination: to delve into Suret-Canale’s studies and track down his sources. This short article is an open door to such an approach and looks forward to being built upon.

Bibliography

Bianchini, Pascal, Ndongo Samba Sylla and Leo Zeilig. Revolutionary Movements in Africa – An Untold Story. Pluto Press, 2024.

Galeazzi, Marco. “Le PCI, le PCF et les luttes anticoloniales (1955–1975)”, Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, n.112–113, 2010, pp. 77–97.

Kipré, Pierre. Le Congrès de Bamako ou la naissance du RDA. Éditions Chaka, 1962.

Madjarian, Grégoire. “La Question coloniale et la politique du Parti communiste français (1944–1947)”. Crise de l’impérialisme colonial et mouvement ouvrier. La Découverte, 1977.

Ruscio, Alain. “2. Le PCF et la question coloniale (de 1920 à 1935)”, Les communistes et l’Algérie. Des origines à la guerre d’indépendance, 1920–1962, sous la direction de Ruscio Alain. La Découverte, 2019, pp. 27–53.

Suret-Canale, Jean. L’Afrique Noire, De la Colonisation aux Indépendances. Éditions Sociales, 1977.

Suret-Canale, Jean. LES GROUPES D’ÉTUDES COMMUNISTES (G.E.C) EN AFRIQUE NOIRE. l’Harmaltan, 1994.