9 November 2022

Matthew Read

On 9 November 1918, the German Empire was toppled after mass uprisings brought the monarchy and First World War to an end. Triggered by a naval mutiny in northern Germany, the November Revolution spread rapidly throughout the country, as soldiers and workers formed revolutionary councils to establish their own organs of power.

The achievements and limitations of the November Revolution greatly shaped the development of the German state in the fateful decades of the 1920s and 1930s, when fascism emerged from within the Weimar Republic. Analysing the historical lessons of the November Revolution has also been a crucial point of contention within the German workers’ movement, for it raises the question of the working class’s relation to state power. Is the state to be understood as a neutral institution that operates above classes in society? Or is it the instrument of a particular class? Can a workers’ party enter the existing state and bring about socialism through parliamentary reform? Or is it necessary to first destroy the existing state before erecting a new apparatus that can build socialism? These questions were already at the centre of debates within German social democracy before 1918 and they again came to the fore in the period following the Second World War when the fate of socialism in Europe was decided. To mark the anniversary, this article briefly examines both the immediate consequences and the long-term influences that the revolution had on social democratic and communist forces in Germany.

The declaration of two republics

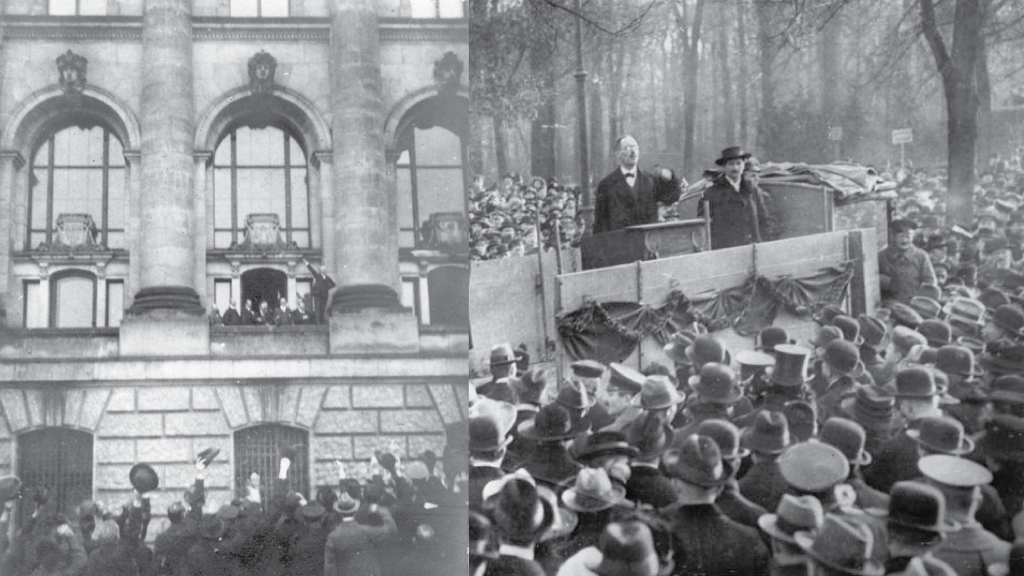

At noon on 9 November 1918, the abdication of the emperor Kaiser Wilhelm was announced to the German public. Within hours, two competing political forces in Berlin declared republics to replace the empire. The first was proclaimed by the reformist leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who was determined to prevent the mass uprising from escalating into a social revolution, as had happened a year prior in Russia. The second was proclaimed by Karl Liebknecht, leader of the Spartacist League, a revolutionary and anti-war breakaway from the SPD. Liebknecht explicitly declared a socialist republic that would represent “a new state order of the proletariat, an order of peace”. In the weeks that followed, these two forces struggled to determine the fate of the country, with the SPD attempting to maintain parliamentary order and the Spartacist League – which merged with various smaller revolutionary groups in December 1918 to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) – championing the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils.

To counter the revolutionary potential of the uprising, the SPD leadership swiftly entered into agreements with the militarist Junker class (the landed aristocracy), promising that the old social order and military apparatus would be preserved under a new republican facade. In return, the military agreed help to crush the revolutionary councils throughout the former empire.

Far-right paramilitary troops began coordinating with the SPD government in Berlin to arrest and execute thousands of revolutionaries, including Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg who were killed in January 1919. With the communists and socialists dispersed and leaderless, the November Revolution was broken off and the SPD was able to cement its vision for the country in the new “Weimar Republic”: the working class was to achieve socialism by entering the bourgeois state and fighting for reforms within the parliament, not by erecting its own organs of state power as the Bolsheviks had advocated in Russia.

The constitution of the Weimar Republic went only so far as to secure formal political democracy. In the name of the “separation of powers”, legislation was to be democratically legitimised through an elected chamber, but the administrative and judicial branches of government remained in the hand of the old imperial bureaucracy, free from popular scrutiny. At the same time, reactionary forces were able to rescue their positions of economic and social dominance by granting certain limited concessions to the masses, such as the 8‑hour workday, the introduction of workers’ councils in factories, and the right to vote for women. The magnates thereby retained control over the industries, the landed nobility preserved their massive estates, and the imperial military command maintained its status as “a state within the state”.

Thus, while the November Revolution of 1918/19 swept away the monarchy and established a constitutional republic, it ultimately failed to fully democratize German society. The economic relations that had given rise to imperialism were further entrenched in the new republic and the imperial state apparatus remained largely intact. As a consequence, the forces that had set the First World War in motion in order to violently secure a leading position for German monopolies in Europe still held key positions from which they could influence subsequent developments.

Indeed, in the decade that followed, German imperialism re-emerged in an even more terroristic and dictatorial form. Finance capital and the reactionary military command had resented both the democratic gains achieved by the November Revolution and the loss of the war, which had brought with it significant territorial losses alongside punitive measures under the Treaty of Versailles. From the earliest days of the Weimar era, these forces fought to roll back workers’ rights (such as reintroducing the 10-hour workday in 1923) and “regain” what had been lost after 1918. To this end, they began supporting and mobilising fascist groups, including Hitler’s Nazi party.

After being hoisted to power in 1933, the Nazis swept away all democratic gains from the previous decades and decimated the working-class parties at home – both the SPD and the KPD were banned, and its cadres sent to concentration camps – before embarking on a war of annihilation abroad. The fascists initiated the Second World War to secure what the First had failed to, namely, a dominant role for German capital worldwide.

Learning from past mistakes

For many within the SPD, the Weimar Republic’s facilitation of fascism and the subsequent horrors of Nazi rule served as a stark lesson that the revolution could not settle for half measures: unless reactionary forces were completely deprived of economic and political power, they would be able to restore their rule. Otto Grotewohl, who had served as a member of parliament for the SPD and state-level minister throughout the Weimar years, came to lead a faction of social democrats that saw the necessity of a rigorous democratisation of post-war society in Germany:

“Today, as then, leading representatives of social democracy overestimate the significance of formal democracy, overlooking the fact that as long as class relations have not been changed, as long as power relations in state and society have not been thoroughly transformed, democracy is only a screen for the old reactionary powers, to be tossed aside as soon as monopoly capitalists and Junkers think the time is ripe”.[1]

After the fascist Wehrmacht capitulated to the Allied powers in May 1945, Germany was divided into four occupation zones. In the Soviet zone, the anti-fascist parties that had been banned by the Nazis were permitted to reorganize. A group of SPD leaders formed an Executive Committee in Berlin and published a declaration on 15 June stating: “Above all, we want to lead the struggle for the restructuring [of Germany] on the basis of the organisational unity of the German working class! We see in this a moral reparation for political mistakes of the past, in order to give the young generation a united political organisation of struggle”. By reunifying the workers’ movement upon the basis of revolutionary Marxism, the mistakes of 1918/19 were to be avoided: those who had fuelled the war were to be expropriated and new, democratic state institutions were to be erected.

The SPD and KPD in the Soviet zone began months of debate on the question of forming a unified working-class party. A central aspect in this debate was the critical reflection on the role of the SPD leadership during the November Revolution. Grotewohl, as chairman of the SPD in the Soviet zone, was a key figure to initiate this process of rethinking in his party. He strongly criticised the bourgeois conception of the state as a neutral institution, as something that operates above classes rather than as an instrument of a particular class:

“For the [November] Revolution this [neutral understanding of the state] had to have fatal effects, for its logical consequence was not struggle against the state, not smashing the state, but instead the subjugation of the working class to the state under the pretext of ‘utilising’ it and safeguarding ‘peace and order’. Since the question of smashing the old state was not posed from the beginning as the central question of the revolution, the struggle was lost before it had even begun”.[2]

Grotewohl concluded that the division of the working class and the reformist attitudes of the social democratic leadership were largely responsible for the failure of the November Revolution. In April 1946, the SPD and KPD merged in the Soviet zone to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED). This process developed differently throughout Germany, as the will to merge was strong in some regional party groups (such as in Thuringia) and particularly divided in others (such as in Berlin).[3] The faction of the SPD that rejected the Executive Committee’s analysis gathered in West Germany. They vehemently held on to reformist notions of reaching socialism through bourgeois democracy and denounced the SED.[4]

Finishing what had been started

In post-war Eastern Germany, a coalition bloc was formed amongst the social democrats, communists, conservatives (CDU) and liberals (LDPD) to carry out an “antifascist-democratic transformation”. Together with the Soviet military administration, this “antifascist-democratic bloc” organised a land reform to both restore the supply of food and break the power of the Junker class. Key industries were nationalized to divest “war criminals and those interested in war” of economic power. The tenured civil service caste was abolished, and entirely new structures were established in the administrative, police, justice, and school systems. Comprehensive social insurance and health care systems were also created alongside workers’ and peasants’ colleges to dismantle the class barriers that had long plagued German society.

The antifascist-democratic bloc and the Soviet military administration in East Germany thus completed the task that the November Revolution had begun: the total elimination of the economic roots of German imperialism and the democratisation of society. This process took place under an increasingly tense international situation, as the temporary war alliance between the Western powers and the Soviet Union dissolved, and the global struggle between imperialism and socialism resumed on all fronts. In the face of post-war destruction, massive reparations payments, and a remilitarizing West German state, the transformation in East Germany was a difficult and at times contradictory process, but its completion marked the culmination point of the revolutionary process that had erupted 30 years prior, in November 1918. The German Democratic Republic (DDR), which was founded in East Germany in October 1949, embodied a new kind of state – one that was based not on the capitalist and aristocratic classes, but on worker and peasant power.

[1] Otto Grotewohl: Thirty Years Later, Dietz-Verlag, Berlin, 1948, p. 10

[2] Otto Grotewohl: Thirty Years Later, Dietz-Verlag, Berlin, 1948, p. 128

[3] The history of this merger has been particularly controversial, both within the communist movement and liberal historiography. The purpose of this article is not to examine the unification of the two parties, but the IF DDR plans to return to the topic alongside the broader development of the SED in future texts.

[4] By 1959, the SPD in West Germany had officially renounced Marxism and committed itself to reforming capitalism rather than replacing it.