21 April 2022

Matthew Read

The Socialist Unity Party (SED), which led the German Democratic Republic from 1949 to 1989, was founded in April 1946, just over three-quarters of a century ago. The established narrative today tells of a group of Moscow-controlled communists returning to Berlin in 1945 to snuff out the social democrats, peel off a separatist state and erect a Soviet-style regime in “East Germany”.

The evidence, however, reveals quite a different story: following the liberation from fascism in May 1945, German socialists and communists set out to establish a neutral, parliamentary republic in which an alliance of antifascist parties – a diverse Popular Front – would shape the future of the country. It was the aspiration of many members of the German workers’ movement that the united working class would, within this new parliamentary framework, be free to win over the people to the socialist cause. This strategy of a gradual and relatively peaceful path to socialism was developed for the specific conditions present in post-war Germany.

Yet the nation’s historical development was famously characterised by a sharp division between the capitalist West and the socialist East. In outlining the events that led to this division and highlighting aspects that are often omitted in prevailing accounts today, this article seeks to examine the development of socialist strategies within their historical context and draw out lessons concerning the general contradictions latent in societal transformations.

The main period in focus here (1945–1952) also marks the formative years of Transatlanticism and the creation of the so-called “security architecture” that has continued to shape relations in Europe long after the end of the Cold War. Recognising the origins and purpose of this architecture is vital for understanding developments in Europe today.

The fatal division of the German working class

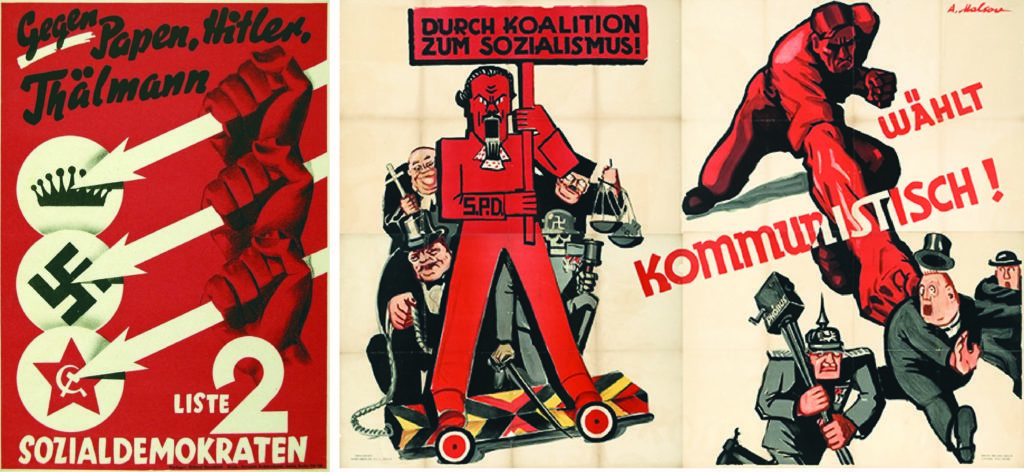

The post-war strategies of German socialists and communists were largely a reaction to the split in the workers’ movement at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1912, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) had established itself as the strongest working-class party in Europe, securing over a third of the vote and becoming the largest faction in the German parliament. Internal divisions had, however, already begun to fracture the party, most famously between reformist and revolutionary tendencies. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the party ruptured along these pre-existing lines of division. Right-wing social democrats endorsed Kaiser Wilhelm’s call for a cross-class truce (“I no longer see political parties; I only see Germans!”) and voted for credits to fund the war. Anti-war members of the SPD denounced the party’s leadership and went on to form their own organisations in the years that followed. There were attempts to unite both reformist and revolutionary anti-war tendencies under the banner of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), but they proved ineffective at halting the war.

By 1918 it was clear that the war effort was running out of steam. After sporadic strikes throughout that year, a wide-spread revolt broke out amongst German soldiers and workers in November. In the power vacuum that followed the abdication of the Kaiser, revolutionaries within the USPD broke away to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and sought to secure power for the soldiers’ and workers’ councils that had emerged. Right-wing Social Democrat leaders moved to prevent a social revolution of the kind seen in Russia a year prior. Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the SPD, assured the militarist Junker class (the landed aristocracy) that his party would merely erect a new republican façade to the old social order.1This was the so-called “Ebert–Groener pact” In return, the Junkers would commit the troops under their command – the so-called Freikorps – to Ebert’s government so that the communist uprisings throughout Germany could be quelled. Thousands of revolutionaries, including Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, were killed in the subsequent months.

The SPD thereby secured its position within the new German state (the “Weimar Republic”) and the split in the workers’ movement had been cemented. The KPD recovered from the wave of repression and continued to agitate for proletarian revolution. In December 1920, 400,000 members of the USPD merged with KPD, whereafter the USPD faded from the political scene. The SPD maintained its alliance with the propertied classes and repeatedly mobilized the forces of the state to quash a series of revolutionary uprisings throughout the 1920s.

With the crash of the capitalist world economy in the early 1930s and increasing unrest among the unemployed and pauperized workers, the propertied classes began to consider more extreme forms of rule to secure their rate of profit and shore up the existing economic order. Coal and steel magnates such as Emil Kirdorf, Fritz Thyssen and Albert Vögler began subsidising the reactionary forces gathering around Hitler.2See: William L. Shirer (1960) Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Fawcett Crest. Fascism repudiated the idea of class struggle and instead upheld monistic ideals: “Eine Volksgemeinschaft ohne Klassen”3See: Otto Grotewohl (1945), Woher, wohin? (one people without classes). Rich or poor, all “true” Germans were said to be part of a harmonious whole. Corporations such as I.G. Farben and Krupp, alongside bankers and insurance companies, soon joined this ultra-nationalist bandwagon, pouring significant sums into the coffers of Hitler’s party.

The deep division in the workers’ movement proved fatal in the struggle against the rising fascist tide. The SPD equated communists with the fascists and refused to work with the KPD at every step. They instead maintained their alliance with the conservative forces that would eventually hand power to Hitler in 1933.4See Reich Presidential Election 1932, where the SPD supported Hindenburg, who named Hitler chancellor less than a year late. For its part, the KPD struggled to produce a clear analysis of fascism, viewing social democracy as a form of “social fascism”. The communists eventually undertook initiatives to unite the working class in a “proletarian unity front” against Nazism, but it was too late. In November 1932, on the eve of the fascist seizure of power, the two workers’ parties secured 13 million votes, but they were split: the SPD obtained 7.2 million and the KPD 5.98 million. The Nazis received 11.7 million votes.

Hoisted into power by the monopolists in 1933, the fascists summarily decimated the workers’ movement. Trade unions were shattered, workers’ associations outlawed, and most SPD and KPD functionaries either fled the country or were imprisoned in concentration camps. Minimum wages, overtime pay, and workplace safety laws were thereafter abolished. Sections of the formerly organized working class continued to resist fascist rule from within Germany, but they remained scattered and cut off from their comrades abroad.

The development of a new strategy: an antifascist-democratic German republic

In January 1935, communist and workers’ parties convened in Moscow for the 7th World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern). Reflecting on the failure to prevent the rise of fascism, the delegates concluded that the tactic of the “proletarian unity front” had been inadequate and a new approach revolving around an “antifascist popular front” was formulated. The new tactic sought to mobilize the broadest layers of society – even amongst the bourgeoisie – to resist fascism and the threat of war. The workers’ front was to operate as the nucleus of the broader, class-pluralist popular front. The tactic was subsequently employed in several countries, most notably in Spain and France.

Following the Comintern congress, exiled KPD leaders held two conferences in which a popular front tactic was developed and applied to the national conditions in Germany. At the 1935 “Brussels Conference”5The conference was in fact held in Moscow but used a misnomer to throw off the Gestapo., the KPD criticized its previous relations with the SPD and its attitude towards bourgeois democracy in the face of fascism. “One-sided, sectarian and outdated” views or orientations were to be corrected.6See: Autorenkollektiv (1978), Geschichte der SED, Dietz Verlag. “All parts of the working class and its organisations, the peasantry, the intelligentsia, the small business owners, and all other opponents of the Hitler regime – right into the bourgeoisie” had to be united in the antifascist struggle. The immediate objective was the overthrowal of the Hitler regime and the establishment of a “free, antifascist German state”.

The following KPD conference was held in France7The “Bern Conference” – another misnomer. in 1939. Here, the popular front tactic was developed into a broader strategy for a post-fascist Germany. In a resolution titled “The path to the overthrowal of Hitler and the struggle for the new, democratic republic” the party declared:

“The new democratic republic, however, in contrast to the Weimar Republic, will root out fascism, deprive it of its material basis through the expropriation of fascist trust capital and, again in contrast to the Weimar Republic, create staunch defenders of democratic freedoms and rights among personnel in the army, police and civil service. In the new democratic republic, in contrast to Weimar, the upper bourgeoisie will not be able to direct its economic and political attacks against the people under the guise of a coalition with a workers’ party, but instead the united working class, together with the peasants, the middle class and the intelligentsia in the Popular Front, will determine the fate of the country.“8See: Klaus Mammach (1974), Die Berner Konferenz, Dietz Verlag.

Thus, the popular front tactic was expanded into a strategy not only for overthrowing the Hitler regime, but also for carrying out a rigorous “antifascist-democratic transformation” and constructing a fundamentally new state in Germany. This new republic would complete what the November Revolution from 1918/19 had failed to, namely a thorough bourgeois revolution. Yet it was to be led not by the bourgeoisie but by the united working class in a Popular Front with the other antifascist forces in society.

According to the resolution, the new strategy was not an “abandonment by the working class of the struggle for socialism,” but rather the acknowledgement that fascist rule in Nazi Germany – where anti-communism was a state doctrine – would drastically set back the socialist cause. Only a gradual transition towards socialism would be possible under these conditions: “With a Germany led by the Popular Front, the socialist and communist workers and organisations will have full freedom to win the majority of the people to the socialist goal.” The antifascist-democratic republic would thus “pave the way to socialism”.

This strategy was also in line with the geopolitical interests of the Soviet government, who sought above all else to neutralise the German imperialism that had instigated two world wars within the first half of the 20th century.9This objective is clear in Soviet communication with the Allied governments from 1941 onwards. See: Wilfried Loth (1994), Stalins ungeliebtes Kind and Herbert Graf (2011), Interessen und Intrigen: Wer spaltete Deutschland? Germany was not only a large central European state straddling the border between East and West, but it was also one of the most industrialised countries in the world with a numerically strong working class and exceptional labour productivity. A powerful workers’ movement operating freely within a parliamentary framework could act as a safeguard against a reconciliation between the German bourgeoisie and the West on an anti-communist basis.10This was the strategy as interpreted by the historian Kurt Gossweiler in his 1998 article “Benjamin Baumgarten und die ‘Stalin-Note’ ” Thus, when negotiating the future of Germany with its allies in the anti-Hitler coalition, the Soviet government set out to secure conditions as favourable as possible for the establishment of a neutral, parliamentary Germany.

A reunited working class and a disempowered bourgeoisie

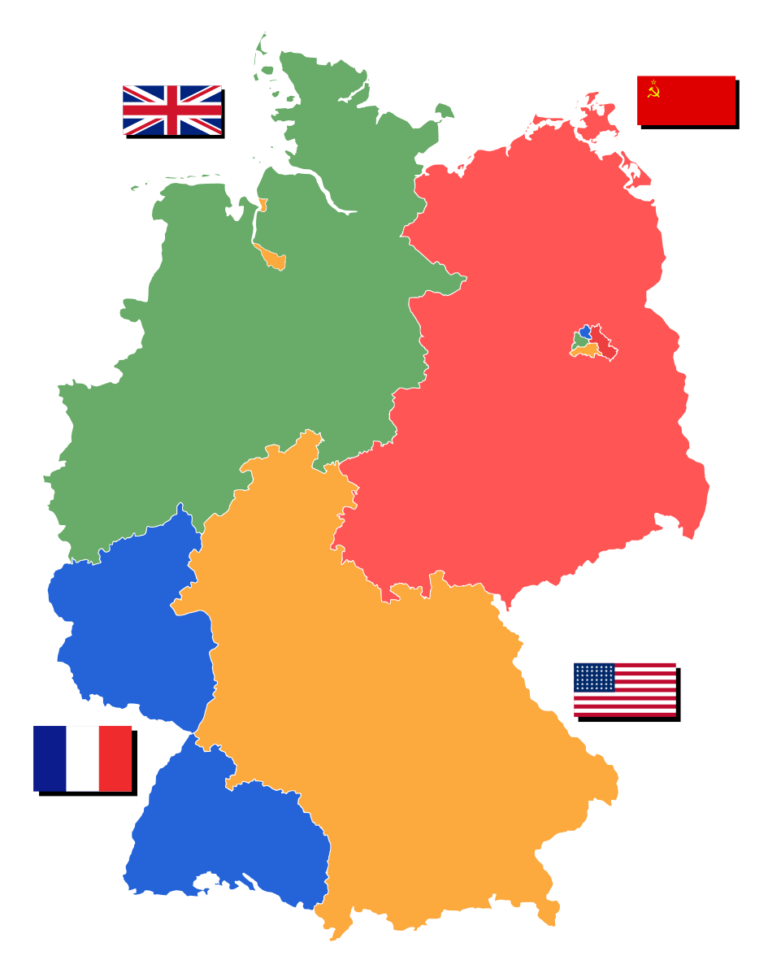

Following the unconditionally surrender of the Wehrmacht to the anti-Hitler coalition on 8 May 1945, Germany was divided into occupation zones as laid out at the Yalta Conference in February 1945. The Allies were agreed that Germany must be prevented from starting another war, but there was no consensus about how this was to be achieved. The UK had pushed for the partition of Germany since 1941 and the US since 1943.11Since Churchill’s telegram to Stalin on 22 November 1941, the UK consistently advocated for isolating Prussia from the rest of Germany. The US followed suit, as is evident in the the plans proposed by the US Secretary of State Cordell Hull at the Moscow Conference in 1943. The Soviets, in contrast, had refrained from any commitment to such a partition. A neutral, demilitarised Germany aligned with neither East nor West remained the Soviet’s preferred solution, yet their main concern during the war years was maintaining cohesion in the anti-Hitler coalition.

At a subsequent conference in Potsdam in August 1945, Allied leaders signed an agreement stating that Germany would initially be governed by four military administrations but “regarded as a single economic entity”. The Potsdam Agreement also stipulated the basic political guidelines to be carried out by the US, British, French, and Soviets in their zones. These were the “four Ds”: denazification to remove all fascists from relevant positions and punish war criminals; demilitarisation to completely disarm and destroy the German arms industry; democratization to restructure public life; and decentralisation to crush “the existing excessive concentration of economic power, embodied especially in the form of cartels, syndicates, trusts and other monopoly associations”. The “four Ds” meant nothing less than the uprooting of German imperialism and the creation of a demilitarised, de-monopolised Germany.

On 10 June 1945, the Soviet Military Administration authorized the establishment of democratic political parties in the Soviet Occupied Zone (SOZ). Antifascists remerged from exile, underground networks, and concentration camps to organise the first parties: the KPD, SPD, Christian Democrats (CDU) and Liberal Democrats (LDPD). In accordance with the strategy developed in exile, the KPD published an appeal on 11 June 1945:

“Together with the destruction of the Hitler regime it is necessary to complete the democratisation of Germany, the bourgeois-democratic transformation which had begun in 1848. It is necessary to completely eliminate the feudal remnants and to destroy the reactionary Prussian militarism with all its economic and political offshoots.

We are of the opinion that imposing the Soviet system on Germany would be wrong because this does not correspond to the present conditions of development in Germany.

On the contrary, we are of the opinion that the decisive interests of the German people in the present situation dictate a different path for Germany, namely, the path of establishing an antifascist, democratic regime, a parliamentary-democratic republic with all democratic rights and freedoms for the people.”

With the destruction of the Third Reich, KPD leaders recognized that the German bourgeoisie was politically and militarily disempowered. In other words, for the first time in Germany’s modern history, the capitalist class was unable to use the forces of the state to suppress the proletarian-socialist movement. The “four Ds”, moreover, would cement this fact and prevent the upper bourgeoisie from regaining control by extended democracy into the economic sphere. According to leading KPD functionary and theoretician Anton Ackermann, these circumstances could open a peaceful parliamentary path to socialism in Germany:

“It is our misfortune that the Hitler regime was not overturned by a revolutionary, anti-fascist-democratic upheaval from within. But, according to the decisions of the Potsdam Conference, the reactionary Prussian-German militarism is to be liquidated down to the last vestige. … The German people are assured the possibility of building a new democratic Germany. Consequently, the question of the way forward resolves itself into the following further question: If the new democratic state develops as a new instrument of violence in the hands of the reactionary forces, then the peaceful transition to socialist transformation is impossible. If, however, the antifascist-democratic republic develops as a state of all labouring masses under the leadership of the working class, then the peaceful road to socialism is quite possible, insofar as the use of violence against the (incidentally perfectly legal, perfectly lawful) claim of the working class to power is excluded.”12While Ackermann’s position is often presented today as a break with the Soviet line, it is clear that Stalin approved of this approach. SED leader Walter Ulbricht met with Stalin just several days before Ackermann’s article was published in February 1946 and both agreed on a democratic path to socialism that would avoid establishing any dictatorship. See Graf (2011). For the quote, see Anton Ackermann (February 1946), “Gibt es einen besonderen deutschen Weg zum Sozialismus?” in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus, Das Neue Berlin (2005).

As such, the new antifascist-democratic republic would possess a different class character:

“It would be childish, of course, to speak as if this democracy with multiple parties, with a constitution, as if this democratic republic would be anything like a republic of the old, bourgeois-capitalist type. No, this is a kind of democracy, a democratic republic, as Lenin envisaged it in 1905, as a state which is also a class state, but a class state in the hands of the workers and peasants.“13Anton Ackermann (March 1947), “Unser Weg zum Sozialismus” in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus, Das Neue Berlin (2005).

As the KPD leadership understood it, this was the particular historical junction at which Germany’s progressive forces stood in the immediate aftermath of the war. For this parliamentary-democratic path to socialism to be successful, the organised working class needed to reunite:

“Only the unification of the KPD and the SPD, and with it the growth of the socialist forces to a million active comrades, can guarantee that it is not the reactionary upper bourgeoisie but the working class and the labouring people who determine the course of further development.…

If, before the victory of the workers over the bourgeoisie, Germany succeeds in establishing the political and organisational unity of the workers’ movement on the basis of consistent Marxism, this circumstance will also shape the further political development in a substantially different way than after the victory of the October Revolution in Russia, which saw the victory of the Bolshevik party and the defeat and eventual crushing of the Mensheviks (which had become a counter-revolutionary party). In this case, a peculiarity of the German development may be that a stronger (and consequently sharper) internal struggle need not break out in the working class and the labouring people after their class victory over the bourgeoisie. Such a fact should also result in a rapid unfolding of consistent socialist democracy.“14Anton Ackermann (February 1946).

Exiled social democrats such as Max Fechner had already advocated for the creation of “a united organ of the German working class” in the final days of the war.15Cited in Graf (2011). An Executive Committee of the SPD was elected in Berlin on 11 June 1945. Its founding declaration called for the “organisational unity of the German working class” and the Committee thereafter opted to join a four-party coalition in the SOZ with the KPD, CDU and LDPD to form to “the antifascist-democratic bloc” in August 1945.

In April 1946, the SPD and KPD merged to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED) in the SOZ. This unification took place after months of contentious debates in which decades of intra-class differences were thrashed out. There was dissension within both parties – the mutual aversion from the Weimar years had not disappeared. Yet, after 12 years of fascist rule, there was broad support amongst both parties’ bases for rectifying past mistakes and closing the ranks of the working class.16Attitudes varied in different regions across Germany. In Thuringia, for example, there was general consensus amongst SPD and KPD members for a unification. In Berlin, however, the SPD went through a bitter internal struggle. Yet even here, significant sections of the party were in favour of an alliance with the KPD. While modern historiographies focus almost entirely on the coercive measures employed by certain SMAD officials during this period to write the union off as a “forced merger”, such incidents do not refute the fact that there was widespread support for a unity party. This point has been made by historians such as Jörg Roesler (2010), Geschichte der DDR and Herbert Graf (2011). The social democrats remained particularly split over the unification question, but the KPD’s thesis of a parliamentary-democratic path to socialism helped to bridge the divide for many left-wing members.

The SED’s founding texts make it clear that, far from aiming to erect a “communist dictatorship” or peel away an East German separatist state, the party sought to work “with all its energy against sectionalist tendencies for the economic, cultural and political unity of Germany”. The “struggle for socialism” was to take place within a parliamentary-democratic republic from where the SED would have the freedom to win over the people. Yet, if the capitalist class within Germany attempted to prevent or reverse the antifascist-democratic transformation, the organised working class would not hesitate to engage in open class struggle once again:

“The fundamental prerequisite for the establishment of the socialist social order is the conquest of political power by the working class. In doing so, it allies itself with the rest of the working people. The Socialist Unity Party of Germany is fighting for this new state on the soil of the democratic republic. The distinctive situation in Germany at present, which has arisen with the break-up of the reactionary state apparatus of violence and the building of a democratic state on a new economic basis, includes the possibility of preventing the reactionary forces from standing in the way of the final liberation of the working class by the means of violence and civil war. The Socialist Unity Party of Germany strives for the democratic road to socialism; but it will resort to revolutionary means if the capitalist class leaves the soil of democracy.“17See: Grundsätze und Ziele der SED from 21 April 1946

In the “Manifesto to the German People“18See: Manifest an das deutsche Volk, Neues Deutschland from 23 April 1946, published that same month, the SED explicitly welcomed private petty-capitalist actors and proclaimed “No one-party system”. Yet for the parliamentary-democratic path to succeed, it was necessary to carry out the “four Ds” and prevent monopoly capital from regaining control of the state. The Soviet Military Administration (SMAD), together with the antifascist-democratic bloc, thus carried out an extensive land reform to dismantle large Junker estates and redistribute land to more than half a million landless peasants. A broad industry reform was initiated to divest “war criminals and those interested in war” of economic power. Monopolistic enterprises were expropriated and transferred into “people’s property”. The nationalised industrial sector was to operate alongside smaller private capitalist enterprises.19By 1948, the SOZ’s gross output was composed of 39% from the publicly owned sector, 39% from private small and medium-sized enterprises, and 22% from Soviet joint stock companies. See: Roesler (2010). Unrepentant members of the former Nazi party were removed from all areas of society including the state, police, medicine, law, and culture. Comprehensive social insurance and health care systems were established alongside workers’ and peasants’ colleges to dismantle class barriers. The tenured civil service caste was abolished, and social polarisation largely eliminated. These measures lent the antifascist-democratic bloc broad support amongst the working masses in these years.20Ibid.

The Potsdam Agreement was thus rigorous and swiftly implemented in the SOZ – the material basis of German imperialism had been eradicated by the end of 1946.

Restoration in the West

The development in the Western occupation zones took a very different path. As in the SOZ, there was a broad consensus amongst diverse groups and parties in Western Germany that the capitalist economic order had lost its credibility. Over a decade of fascist rule and the destruction left by the war had made this evident. Calls for the socialisation of key industries and elimination of monopoly capital could be heard from not only the communists, social democrats, and trade unions – even the conservative CDU party disavowed capitalism in their 1947 “Ahlener” programme and propagated “Christian socialism”. Yet despite these convictions, Western military administrations soon began obstructing popular socialisation and land reform initiatives that had been allowed for (and in fact prescribed) in the Potsdam Agreement.21Early moves by parties within the Western zones to create legal stipulations to socialise key industries or reform land relations were rejected by the respective military administrations. In Hessen, for example, where the SPD and KPD held a majority in the state government, a constitution was drafted in which Article 41 stipulated the socialisation of key industries and the public administration of banks. Although this Article in no way violated the principles of the Potsdam Agreement, the US military administration wanted it removed from the constitution. A public referendum on Article 41 in December 1946 showed 72% of voters to be in favour. US General Lucius Clay nevertheless prohibited its implementation. A planned land reform was similarly prevented in the US zone. In the British zone, a limited land reform was initiated in 1947 after many delays, but it left existing agricultural structures largely unaltered. See: Georg Fülberth (1983), Leitfaden durch die Geschichte der Bundesrepublik, Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag. Attempts to establish a united cross-industry trade union were also hindered by the authorities. Only decentralised trade unions would be allowed in the Western zones.22See Herbert Graf (2011). Efforts to merge the SPD and KPD were similarly hampered, as meetings and demonstrations promoting the merger were banned. Right-wing forces within the SPD were assisted by the British administration in erecting a separate west German party organ to exclude pro-merger voices and rival the SPD Executive Committee in Berlin. The state governments in the Western zones that had been led by Popular Fronts (cross-party coalitions ranging from the CDU to the KPD) also succumbed to the growing Red Scare by the end of 1947.23For example, the state governments of Nordrhein-Westfalen (1946–48) and Rheinland-Pfalz (1946–48)

These developments reveal that the KPD’s post-war assessment of Germany had been correct in one sense: broad sections of the German population were indeed calling for an antifascist and anti-monopolistic transformation of the country. Yet what their assessment had underestimated was the haste and cohesion with which the capitalist powers would move to prohibit popular initiatives and disregard the Potsdam Agreement. By stifling the workers’ movement (both the trade union movement and the SPD-KPD merger), the Western administrations also ensured that these initiatives remained uncoordinated and diffuse. The monopolistic industries and Junker estates were thereby left unaltered in the Western zones, and this undermined the very basis of the antifascist, democratic strategy. The working class remained divided and weak, while the upper bourgeoisie retained their grip on the economy.

In hindsight, it is clear that key players within the Western powers never had any serious intentions of cooperating with the Soviets: The US and UK had assumed until the end of 1944 that their forces alone would occupy Germany after Nazi capitulation.24Winston Churchill recounted this assumption in his series The Second World War, cited in Graf (2011). Yet, with the rapid advance of the Red Army through eastern Europe, Western leaders began secretly exploring ways of “containing” Soviet influence. Two of the now known examples were “Operation Sunrise” (February-May 1945) and “Operation Unthinkable” (May 1945), where Western intelligence services had explored the possibility of uniting with Wehrmacht divisions to hinder the Soviet advance.25“Operation Sunrise” was initiated in February 1945, when the US and UK began secret negotiations with high-ranking SS generals in Switzerland. The negotiations took place with the blessings of Himmler and Hitler in the villa of German industrialist Edmund Stinnes. The Swiss intelligence services and the private attaché of Pope Pius XII played mediatory roles. The discussion focused on whether the Wehrmacht could form “a common front with the Allies against the advance of the Soviet Union in Europe”. When the Soviets learnt of these meetings, they demanded a seat at the table, but were prohibited by the US. This event shook Soviet trust in the anti-Hitler coalition. The Soviet government, who had hitherto treated US and UK plans to fragment Germany with quite reservations, now openly rejected partition. “Operation Unthinkable” was ordered by Churchill after German capitulation in May 1945. The operation explored the possibility of a surprise attack against Red Army troops in Germany “to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire.” Wehrmacht battalions were to be remobilised and rearmed for this purpose. See: Herbert Graf (2011), Interessen und Intrigen: Wer spaltete Deutschland?

These operations were ultimately deemed too risky and Western leaders conceded that Soviet influence would extend inside Germany.26Churchill telegrammed to US President Truman on 4 June 1945: “I view with profound misgivings the retreat of the American Army to our line of occupation in the Central Sector [of Germany], thus bringing Soviet power into the heart of Western Europe and the descent of an iron curtain between us and everything to the eastward.” See: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945Berlinv01/d50 They thereafter adopted a strategy of “containment”. As top US diplomat George Kennan wrote in an internal document in the summer of 1945, “Better a partitioned Germany, of which at least the western part acts as a buffer for the forces of totalitarianism, than a united Germany which lets these forces again reach the North Sea.“27George Kennan (1982), Memoiren eines Diplomaten cited in Herbert Graf (2011). A West German separatist state was thus to act as a bulwark against the socialist advance and it was presumably for this reason that Western leaders refused the Soviet proposal from 30 July 1945 for the formation of a unitary German central administration with quasi-governmental functions to work alongside the Allies’ military administrations.

This containment strategy could not risk an anti-monopolistic, parliamentary republic unfolding in Germany, for this would likely pave the way for socialist development. As Erich Köhler, the first President of the West German parliament, later said, “We reject the unity of Germany if this allows the socialist forces to rule over the whole country.” Thus, regardless of the population’s wishes, the Western military administrations set out to reimpose monopoly relations so that bourgeois rule could be restored. In March 1946, a month before the SED was founded in the SOZ, Churchill delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech in which he contrasted “the liberties enjoyed by individual citizens throughout the British Empire” with “totalitarian control” in Eastern Europe and warned that “communist fifth columns” in the West constituted a “peril to Christian civilisation”.

When challenged about their unwillingness to implement the “four Ds”, Western officials argued that the Potsdam Agreement merely represented a conference communiqué rather than a legally binding treaty. Thus, although they had agreed that “during the period of occupation, Germany is to be regarded as a single economic entity”, the UK and US fused their zones into an “integrated economic area” (the “Bizone”) in January 1947, creating proto-state organs in Western Germany. The French zone was added in April 1948 to create the “Trizone”.

The conservative parties in Western Germany began purging their ranks of anti-monopolist voices. Taking advantage of the disorganised and divided workers’ movement in their zones, these parties set out to establish the West German separatist state envisaged by the US, UK, and France. The figurehead of this endeavour, Konrad Adenauer echoed Kennan when he said, “Better half of Germany whole than the whole of Germany half.”28Adenauer had dismissed the idea of a unified Germany as early as October 1945. See Graf (2011). Fascists and members of the capitalist class began leaving the SOZ in these years, realising that more lucrative prospects and lenient laws awaited them in the West. Indeed, many former Nazi cadres found high-ranking positions in the emerging West German state.

In March 1947, the US announced the “Truman doctrine”, which made their “containment” strategy the official policy of the West. The “Marshall Plan” was developed as the economic arm of this doctrine. Presented in June 1947, the Plan envisioned massive US investment in Western Europe. It would not only provide an outlet for excess US capital following the country’s transition from wartime to peacetime production but would also bind the people of Western Europe to the US economically, politically, and ideologically.29See: Wilfried Loth (1994), Stalins ungeliebtes Kind and See: Georg Fülberth (1983). An economic boom in the Trizone could also help to rehabilitate the free market in the eyes of many West Germans. At the same time, Western administrations sought to increase pressure on the ravaged Soviet economy by reducing trade and cutting the SOZ off from the coal, iron, and steel produced in the heavily industrialised Ruhr area in Western Germany. The US had also suspended reparation payments from their zone to the Soviets in May 1946, again in breach of the Potsdam Agreement. The SOZ had to henceforth bear this burden alone.

To facilitate the Marshall Plan and its stream of US capital into Germany, the Western powers secretly planned to overhaul economic transactions in the Trizone. In June 1948, they introduced a new currency (the “deutsche Mark”) that was tied to the US-Dollar. This currency reform initially shocked the economy as it swept away price controls but left wages frozen. Months of social unrest followed. In October, striking workers in Stuttgart took to the streets to demand the nationalisation of primary industries and the introduction of a planned economy. In response, the US military deployed tanks and teargas. A month later, on 12 November 1948, a massive general strike involving some 9 million workers (72% of the workforce) paralysed the US and British zones, again calling for the socialisation of large industries.30This was the largest general strike since the Kapp Putsch in 1920. It has, however, been largely eradicated from collective memory in Germany. See: Nelli Tügel Interview with Uwe Fuhrmann in Neues Deutschland 09.11.2018 and Jörg Roesler in Der Freitag 07.11.2003. Trizone authorities were able to alleviate the situation by offering concessions such as flexible price control measures and parity financing of health insurance.

Through this currency reform, an exclusive west German economic sphere had been created in the Trizone. During the same period, the foreign ministers of the Western powers had also drafted official plans for the establishment of a West German separatist state. The orders were passed along to Trizone officials on 1 July 1948.31These orders were part of the “Frankfurt Documents” drafted at the London Six-Power Conference in early 1948.

In September of that year, France, the UK, and the Benelux states also entered the Brussels Treaty Organisation, a military alliance aimed against the Soviet Union. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was established seven months later.

A turning point for the SED

The SED and Soviet authorities were thus confronted with a dilemma. The hope for a mass nationwide movement to establish a neutral, democratic Germany was quickly disintegrating in face of heavy-handed Western military administrations. Despite intensive campaigning, the unification of the workers’ movement had been thwarted in the west and popular anti-monopolistic initiatives had been quashed. The bourgeoisie in the Trizone was once again gaining the upper hand. At the same time, the SOZ had to keep pace with economic development in Western Germany – borders remained open and too great a disparity would lead to economic collapse. With reparations to pay and a historically less industrialized territory than Western Germany, the SOZ faced an immense task.

The end of 1947 and first half of 1948 marked a turning point. In response to the deteriorating international situation, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union established the Cominform in October 1947 as an unofficial European successor to the Comintern, which had been dissolved in 1943 to maintain cohesion in the anti-Hitler coalition. Greater political unity amongst European communist parties was to be the answer to the Truman Doctrine. The SED, while not a member of the Cominform, took the cue and began reorienting itself around Leninist organisational principles in 1948 – it was to become a “Party of a New Type” modelled after the Bolsheviks. Emphasis was placed on ideological clarity (cadre schooling) and party discipline. As part of this “Bolshevisation” process, resistant or apathetic members were expelled from the party and the parity principle in leadership between SPD and KPD was dropped. The SED was thereby to become more efficient and better equipped for the intensifying international class struggle.32See: Autorenkollektiv (1978), Geschichte der SED, Dietz Verlag.

In June 1948, a two-year economic plan (1949–1950) was also drawn up to accelerate economic recovery and build up a heavy industrial base in eastern Germany. This was made a necessity after the Western powers halted exports from the industrial heartland of Germany (the Ruhr area). Yet the plan prompted the first serious political dispute within the antifascist-democratic bloc. The LDPD and CDU knew that a concentration of investments in heavy industry would reduce investments in the consumer industries, where their political base (the petty bourgeoisie) resided. After intense debate, the SED prevailed with the two-year plan and the party’s ascendancy in the SOZ was cemented.33See: Roesler (2010).

In March 1947, before a separate economic sphere had been established in the Western zones, the SED theoretician Ackermann had assessed the situation in Germany:

“If we had the same or at least similar conditions in the whole of Germany as in the Soviet occupation zone, we could recognise with a calm and good conscience: The democratic road to socialism is also assured for Germany. Unfortunately, however, we do not have the same conditions in all of Germany. Unfortunately, even in larger parts of Germany the economic power of capitalist reaction has not been eliminated, and this is ultimately the decisive factor for every Marxist. There is no democratic land reform, no industrial reform, and so on. … How this struggle for the unity of Germany and for the reorganisation of Germany will end, no one can predict with certainty today.”

Yet by the end of 1948, the restoration of monopoly capital in the Trizone was undeniable. By September 1948, after his party had been “bolshevized”, Ackermann distanced himself from the question of “a particular German path to socialism”, citing deteriorating national and international conditions:

“The situation has not stood still since the end of 1945, beginning of 1946. We have had new developments in the Eastern zone. We are faced with completely new facts in the Western zones, with the fact that they chose a path leading backwards there, that a reactionary state apparatus is being set up anew under the domination of foreign imperialist powers, threatening every genuinely democratic development … The overall intensification of the international class struggle, the experiences we have made, therefore allow us to consider this question [of a particular German path to socialism] much more acutely than was the case only a short time ago.“34Ackermann’s self-criticism also followed the Yugoslav–Soviet split. Tito had previously professed the idea of a Yugoslavian path to socialism. Anton Ackermann (September 1948), in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus.

As a consequence of capitalist restoration in the West, it would not be long before the German bourgeoisie would regain political and military control there. Indeed, in May 1949, the Trizone officially became a West German separatist state, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).35George Kennan, an architect of the Truman Doctrine, admitted 50 years later that during negotiations with the Soviets the West stood on “demands that we knew the Russians would not and could not accept—demands based upon our plans for the setting up of a west German government in which they would have no place”. While Kennan claims to have lobbied for further negotiations with the Soviets, he reveals that “formidable” forces were “arrayed against” him within the State Department and particularly in the French and British governments who were “terrified at the thought that there might be a unified Germany not under Western, and predominantly American, control.” Incidentally, Kennan also identifies Konrad Adenauer as one of the driving forces for a separatist West German state: “Adenauer, who, powerful and impressive figure that he was, viewed the Germans east of the Elbe, I suspect, as having been (the phrase was, I believe, Sigmund Freud’s) ‘baptized late and very badly,’ and had no enthusiasm for taking them into the future Germany at all.” See: Kennan (1998), A Letter on Germany: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1998/12/03/a‑letter-on-germany/ The new government claimed to be the successor of the German Reich and the only legitimate representative of the German people. The path to a neutral, united Germany had been all but sealed off.36West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer consistently demanded that the first step to any reunification process would have to be “free elections”. Adenauer bet that the significantly larger West German population – now benefitting from the massive investment programmes of the Marshall Plan – would leave DDR voters outnumbered. This, Adenauer believed, would allow all of Germany to be integrated into the Western bloc. The SED leadership demanded that the first step to reunification must be a bilateral conference between two German governments to negotiate the basic socio-economic principles of a reunified state. In other words, the issues at the heart of the Potsdam Agreement – the class character of the post-war German state – would have to be settled before elections could take place. See: Georg Fülberth (1983). The SOZ reacted in October that year with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as a basis for workers’ and peasants’ power. Socialism, however, remained off the immediate agenda.

The establishment of the GDR was therefore the result of an early strategic defeat for the SED and the Soviets. The Popular Front had simply not been viable in the Western zones, where the capitalist class – propped up by their allies in the North Atlantic states – had successfully prevented an antifascist-democratic transformation. Monopolist power had once again been consolidated in a bourgeois-parliamentary state, the FRG. The founding of the GDR was the necessary answer to this defeat. The alternative would have meant total capitulation, reversing all progress made in the SOZ since 1945 and allowing the new Western-aligned German imperialism to extend all the way to the Polish border. The GDR could at least preserve the gains of the antifascist-democratic transformation in the SOZ and, as the SED and Soviets continued to emphasise, it would provide a base for the forces continuing the struggle for a united, neutral Germany. Whether or not this struggle had a realistic chance of success, it is likely that the socialist forces wanted to prevent reactionary forces from co-opting the “national movement” for their own purposes. The workers’ movement thus had to remain the champion of “national interests”.37This is an explanation offered by Gossweiler (1998).

By the end of the 1940s, the international class conflict showed no signs of abating. Marxist-Leninist forces were gaining ground on several fronts, particularly in Asia. The US subsequently began embarking on “rollback” missions that went beyond mere “containment”. Covert and overt Western interventions were carried out in countries such as Albania (Operation Valuable, 1949) and Korea (1950) in an attempt to reabsorb these territories into the capitalist orbit.

In Europe, the remilitarization of West Germany – a further violation of the Potsdam Agreement – soon became a watchword amongst FRG and North Atlantic leaders. In October 1950, West Germany was authorized to establish a provisional defense ministry, and NATO discussed plans to incorporate the FRG into the alliance. A broad movement against remilitarisation spread throughout West Germany, even amongst bourgeois circles.38Adenauer’s own interior minister resigned in 1950, arguing that remilitarisation made the reunification of Germany impossible. Journalists such as Paul Sethe of the “Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung” lost their positions after calling for genuine negotiations with the Soviets. The rank and file of the trade unions underpinned this resistance and, in 1951/52, a popular consultation initiative on the issue received some 9 million votes against remilitarisation, despite being banned.39See: Georg Fülberth (1983). The FRG counteracted such initiatives with its newly established intelligence services (the “Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz”). New laws targeting those “endangering the state” were used to shut down dissent. A ban on the KPD was initiated in 1951 and carried out in 1956. The FRG was thereby able to form a specialised armed police service (the “Bundesgrenzschutz”) in March 1951 as a forerunner to the future Bundeswehr force.

Elements within the SED and particularly the Soviet leadership appeared reluctant to accept the situation for what it was. It is difficult to discern whether this was due to false hopes in the progressive forces in West Germany or to the aforementioned strategic necessity of retaining leadership of the national movement. Stalin repeatedly attempted to resuscitate the prospect of a united, non-aligned Germany. The last effort, the famous “Stalin Note” from 10 March 1952, proposed a unitary Germany that would retain its own national armed forces for defence, but would abstain from coalitions or military alliances directed against any state from the anti-Hitler coalition. The note was swiftly rejected by Western leaders.40The intention behind this note has been greatly disputed. In the West, many accounts initially described it as a bluff. After 1990, some Western historians such as Loth (1994) argued that the note was genuine, describing it as Stalin’s desperate last hope that was ultimately undermined by the SED in July 1952 when “the construction of socialism” was announced. Gossweiler (1998) draws on meeting notes taken by Wilhelm Pieck to argue that the Soviet and SED leadership were actually in agreement throughout these months that the Western leaders would not seriously entertain the idea of reunification. According to Gossweiler, the March note thus served to test the power constellation in the FRG and to force the West to show their true colours.

Following this rejection, SED leaders travelled to Moscow in April 1952 to deliberate with Soviet officials. The Soviets conceded that the establishment of an East German defence force was now a necessity. Yet this rearmament would put additional pressure on the GDR’s already strained economy.…The “Barracked People’s Police” was established in July 1952 and the DDR’s defence expenditure accordingly quadrupled by mid-1953. The resulting financial cutbacks were a significant factor contributing to the 17 June protests in 1953. See Roesler (2010).

The dilemma thus remained the same: while the prospects for a united, neutral Germany had essentially disappeared by 1949, Soviet leadership remained adamant that the struggle had to continue. At the same time, this endeavour could not come at the cost of the GDR’s economic recovery. A collapse of the new state would make the situation far worse than it already was.

The economy of the GDR had hitherto embodied contradictory elements. While a significant portion of the country’s industrial sector had already been nationalized and, since 1948, increasingly integrated into centralised planning, agriculture remained splintered by small and medium holdings following the SOZ’s land reform in 1945–46. To expand the country’s productive capabilities, it would be necessary to transform these holdings into large-scale agricultural operations. This would ultimately require a decision on the relations of production in the GDR: would agriculture develop along capitalist lines into estates concentrated in the hands of a few private individuals or along socialist lines into production cooperatives owned and managed by the peasants themselves?42See: Kurt Gossweiler (1998). In April 1952, the Soviet leadership accordingly approved a transition to cooperative structures in agriculture.

Three months later, at its Second Party Congress in July 1952, the SED declared that the GDR would “proceed to the construction of socialism”.43This announcement had been approved by the Soviet leadership and did not take place behind Stalin’s back as some accounts claim – see Loth (1994). The central aspect of the declaration was the gradual formation of agricultural cooperatives (LPGs) in the countryside.44There were three types of LPGs in the DDR with varying degrees of collectivization. In contrast to Soviet cooperatives (kolkhozy), farmland in the LPGs remained the private property of the individual farmers. The industrial sector, which had already been operating under provisional economic planning for several years, was now to be further centralized. Small and medium private enterprises continued, however, to play a key role in the DDR’s economy for the next two decades. The establishment of a united, neutral Germany remained the long-term strategic objective of the SED until 1971, when the “national question” was deemed closed at the 8th Party Congress.

An artificially divided nation

The concept of an antifascist-democratic transformation had been first developed in the late 1930s, when the popular front tactic was expanded into a broader strategy for a post-fascist Germany. With the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht in May 1945, the German bourgeoisie had indeed been politically and militarily incapacitated, as the KPD had foreseen. The issue was, however, that it was not a domestic popular front, but the armies of the allied powers that liberated the country from fascism. Two-thirds of Germany were thereupon occupied by the militaries of capitalist powers and the fate of the antifascist-democratic transformation ultimately rested in their hands. Thus, while it is undeniable that there were widespread anti-monopolist convictions throughout Germany in the immediate post-war period, the capitalist powers were able to snuff out all attempts to organise and implement popular socialisation demands.

It was then possible to reanimate German imperialism in the FRG in order to “rollback” or at least “contain” the socialist advance. West Germany was thereafter tightly bound into the North Atlantic project, where it would operate as the forwardmost outposts for US hegemony in Europe, much like South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan in Asia.

This early defeat for the SED raises the question of whether the antifascist-democratic transformation was still a viable strategy following the end of the war. Was not the idea of a neutral, unitary state emerging out of the occupied zones an illusion? Indeed, as soon as the threat of fascism had been contained in early 1945, the capitalist powers resumed the anti-communist offensive they had been leading since 1917. The Allied alliance (1941–45) proved to be nothing more than a brief interlude in the inter-systemic confrontation between imperialism and socialism.

The post-war situation was undoubtedly complex, but it seems clear that by 1947 or 1948 at the latest, the prospects for a neutral, democratic Germany had disappeared entirely. The leaders of the SED and particularly the Soviet Union were slow to accept this fact. They remained on the back foot throughout the late 1940s, reacting to developments in Germany rather than determining them. It is worth considering here whether the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943 had left the workers’ movement disoriented in post-war Europe. Would an earlier strategic reorientation not have improved the GDR’s starting conditions for the coming Cold War? Reparation payments, however justified from the Soviet’s national standpoint, set East Germany’s war-torn productive capabilities far behind those of the West.

It is also questionable whether the popular front strategy offered a viable path to socialism in the long run. In the SOZ itself, where a genuine popular front had successfully taken shape in the antifascist-democratic bloc, it was not long before the interests within this broad alliance began to diverge. Once decisions had to be made regarding the country’s economic trajectory (e.g., the two-year plan of 1948), bourgeois elements within the alliance put up resistance and the SED began to force the issue. The Front continued to operate throughout the GDR’s 40-year existence, and the aligned parties managed to influence key policies in the decades that followed, but the dominance of the SED was undisputable after 1948.

While these initial strategies remain open to debate, the socialist forces in East Germany were ultimately able to reorient themselves and – under the protection of the Soviet Union – preserve and consolidate their antifascist-democratic transformation by constructing a workers’ and peasants’ state. The GDR’s founding circumstances were, however, far from optimal. The envisioned gradual progression towards socialism proved untenable and a relatively swift transition to socialism was thus set in motion just seven years after the liberation from fascism. Rather than embodying a neutral buffer zone, Germany was now situated on the front line of an international class conflict. The German people had, furthermore, been artificially divided and a burning “national question” was opened in many minds. Socialism in the GDR thus embodied stark contradictions that the SED and its allies would struggle to navigate in the decades that followed.

Footnotes

[1] This was the so-called “Ebert–Groener pact”

[2] See: William L. Shirer (1960) Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Fawcett Crest.

[3] See: Otto Grotewohl (1945), Woher, wohin?

[4] See Reich Presidential Election 1932, where the SPD supported Hindenburg, who named Hitler chancellor less than a year late.

[5] The conference was in fact held in Moscow but used a misnomer to throw off the Gestapo.

[6] See: Autorenkollektiv (1978), Geschichte der SED, Dietz Verlag.

[7] The “Bern Conference” – another misnomer

[8] See: Klaus Mammach (1974), Die Berner Konferenz, Dietz Verlag.

[9] This objective is clear in Soviet communication with the Allied governments from 1941 onwards. See: Wilfried Loth (1994), Stalins ungeliebtes Kind and Herbert Graf (2011), Interessen und Intrigen: Wer spaltete Deutschland?

[10] This was the strategy as interpreted by Kurt Gossweiler (1998), Benjamin Baumgarten und die “Stalin-Note”

[11] Since Churchill’s telegram to Stalin on 22 November 1941, the UK consistently advocated for isolating Prussia from the rest of Germany. The US followed suit, as is evident in the the plans proposed by the US Secretary of State Cordell Hull at the Moscow Conference in 1943.

[12] Anton Ackermann (February 1946), Gibt es einen besonderen deutschen Weg zum Sozialismus? in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus, Das Neue Berlin (2005). While Ackermann’s position is often presented today as a break with the Soviet line, it is clear that Stalin approved of this approach. SED leader Walter Ulbricht met with Stalin just several days before Ackermann’s article was published in February 1946 and both agreed on a democratic path to socialism that would avoid establishing any dictatorship. See Graf (2011).

[13] Anton Ackermann (March 1947), Unser Weg zum Sozialismus in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus, Das Neue Berlin (2005).

[14] Anton Ackermann (February 1946)

[15] Cited in Graf (2011).

[16] Attitudes varied in different regions across Germany. In Thuringia, for example, there was general consensus amongst SPD and KPD members for a unification. In Berlin, however, the SPD went through a bitter internal struggle. Yet even here, significant sections of the party were in favour of an alliance with the KPD. While modern historiographies focus almost entirely on the coercive measures employed by certain SMAD officials during this period to write the union off as a “forced merger”, such incidents do not refute the fact that there was widespread support for a unity party. This point has been made by historians such as Jörg Roesler (2010), Geschichte der DDR and Herbert Graf (2011).

[17] See: Grundsätze und Ziele der SED from 21 April 1946

[18] See: Manifest an das deutsche Volk, Neues Deutschland from 23 April 1946

[19] By 1948, the SOZ’s gross output was composed of 39% from the publicly owned sector, 39% from private small and medium-sized enterprises, and 22% from Soviet joint stock companies. See: Roesler (2010).

[20] Ibid.

[21]Early moves by parties within the Western zones to create legal stipulations to socialise key industries or reform land relations were rejected by the respective military administrations. In Hessen, for example, where the SPD and KPD held a majority in the state government, a constitution was drafted in which Article 41 stipulated the socialisation of key industries and the public administration of banks. Although this Article in no way violated the principles of the Potsdam Agreement, the US military administration wanted it removed from the constitution. A public referendum on Article 41 in December 1946 showed 72% of voters to be in favour. US General Lucius Clay nevertheless prohibited its implementation. A planned land reform was similarly prevented in the US zone. In the British zone, a limited land reform was initiated in 1947 after many delays, but it left existing agricultural structures largely unaltered. See: Georg Fülberth (1983), Leitfaden durch die Geschichte der Bundesrepublik, Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag.

[22]See Herbert Graf (2011)

[23]For example, the state governments of Nordrhein-Westfalen (1946–48) and Rheinland-Pfalz (1946–48)

[24]Winston Churchill recounted this assumption in his series The Second World War, cited in Graf (2011).

[25]“Operation Sunrise” was initiated in February 1945, when the US and UK began secret negotiations with high-ranking SS generals in Switzerland. The negotiations took place with the blessings of Himmler and Hitler in

the villa of German industrialist Edmund Stinnes. The Swiss intelligence services and the private attaché of Pope Pius XII played mediatory roles. The discussion focused on whether the Wehrmacht could form “a common front with the Allies against the advance of the Soviet Union in Europe”. When the Soviets learnt of these meetings, they demanded a seat at the table, but were prohibited by the US. This event shook Soviet trust in the anti-Hitler coalition. The Soviet government, who had hitherto treated US and UK plans to fragment Germany with quite reservations, now openly rejected partition.

“Operation Unthinkable” was ordered by Churchill after German capitulation in May 1945. The operation explored the possibility of a surprise attack against Red Army troops in Germany “to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire.” Wehrmacht battalions were to be remobilised and rearmed for this purpose. See: Herbert Graf (2011), Interessen und Intrigen: Wer spaltete Deutschland?

[26]Churchill telegrammed to US President Truman on 4 June 1945: “I view with profound misgivings the retreat of the American Army to our line of occupation in the Central Sector [of Germany], thus bringing Soviet power into the heart of Western Europe and the descent of an iron curtain between us and everything to the eastward.”

[27]George Kennan (1982), Memoiren eines Diplomaten cited in Herbert Graf (2011)

[28]Adenauer had dismissed the idea of a unified Germany as early as October 1945. See Graf (2011)

[29]See: Wilfried Loth (1994), Stalins ungeliebtes Kind and See: Georg Fülberth (1983)

[30]This was the largest general strike since the Kapp Putsch in 1920. It has, however, been largely eradicated from collective memory in Germany. See: Nelli Tügel Interview with Uwe Fuhrmann in Neues Deutschland 09.11.2018 and Jörg Roesler in der Freitag 07.11.2003.

[31]These orders were part of the “Frankfurt Documents” drafted at the London Six-Power Conference in early 1948.

[32]See: See: Autorenkollektiv (1978), Geschichte der SED, Dietz Verlag.

[33]See: Roesler (2010)

[34]Anton Ackermann (September 1948), in Der deutsche Weg zum Sozialismus. Ackermann’s self-criticism also followed the Yugoslav–Soviet split. Tito had previously professed the idea of a Yugoslavian path to socialism.

[35]George Kennan, an architect of the Truman Doctrine, admitted 50 years later that during negotiations with the Soviets the West stood on “demands that we knew the Russians would not and could not accept—demands based upon our plans for the setting up of a west German government in which they would have no place”. While Kennan claims to have lobbied for further negotiations with the Soviets, he reveals that “formidable” forces were “arrayed against” him within the State Department and particularly in the French and British governments who were “terrified at the thought that there might be a unified Germany not under Western, and predominantly American, control.” Incidentally, Kennan also identifies Konrad Adenauer as one of the driving forces for a separatist West German state: “Adenauer, who, powerful and impressive figure that he was, viewed the Germans east of the Elbe, I suspect, as having been (the phrase was, I believe, Sigmund Freud’s) ‘baptized late and very badly,’ and had no enthusiasm for taking them into the future Germany at all.” See: Kennan (1998), A Letter on Germany

[36]West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer consistently demanded that the first step to any reunification process would have to be “free elections”. Adenauer bet that the significantly larger West German population – now benefitting from the massive investment programmes of the Marshall Plan – would leave DDR voters outnumbered. This, Adenauer believed, would allow all of Germany to be integrated into the Western bloc. The SED leadership demanded that the first step to reunification must be a bilateral conference between two German governments to negotiate the basic socio-economic principles of a reunified state. In other words, the issues at the heart of the Potsdam Agreement – the class character of the post-war German state – would have to be settled before elections could take place. See: Georg Fülberth (1983)

[37]This is an explanation offered by Gossweiler (1998)

[38]Adenauer’s own interior minister resigned in 1950, arguing that remilitarisation made the reunification of Germany impossible. Journalists such as Paul Sethe of the “Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung” lost their positions after calling for genuine negotiations with the Soviets.

[39]See: Georg Fülberth (1983)

[40]The intention behind this note has been greatly disputed. In the West, many accounts initially described it as a bluff. After 1990, some Western historians such as Loth (1994) argued that the note was genuine, describing it as Stalin’s desperate last hope that was ultimately undermined by the SED in July 1952 when “the construction of socialism” was announced. Gossweiler (1998) draws on meeting notes taken by Wilhelm Pieck to argue that the Soviet and SED leadership were actually in agreement throughout these months that the Western leaders would not seriously entertain the idea of reunification. According to Gossweiler, the March note thus served to test the power constellation in the FRG and to force the West to show their true colours.

[41]The “Barracked People’s Police” was established in July 1952 and the DDR’s defence expenditure accordingly quadrupled by mid-1953. The resulting financial cutbacks were a significant factor contributing to the 17 June protests in 1953. See Roesler (2010)

[42]See: Kurt Gossweiler (1998)

[43]This announcement had been approved by the Soviet leadership and did not take place behind Stalin’s back as some accounts claim – see Loth (1994).

[44]There were three types of LPGs in the DDR with varying degrees of collectivization. In contrast to Soviet cooperatives (kolkhozy), farmland in the LPGs remained the private property of the individual farmers.