Dr. Anandita Bajpai

4 October 2023

Introduction

Radio was a prominent tool of the ‘Cultural Cold War’ for reaching out to people in ‘far away’ spaces, communicating worldviews that prescribed to Cold War-divides, and in forging ideological affinities and animosities alike. Several foreign broadcasting stations based in Europe, USA, and the Soviet Union were specifically established between the 1960s and late 1980s to procure global listening publics. In my field research on the Hindi Service programmes of several radio stations and their audiences in medium-sized cities, townships, and rural villages of India, I have especially been tracing the trajectory of Radio Berlin International, the GDR’s foreign broadcaster based in East Berlin. Whereas much scholarship exists on sonic competition on the ether waves during the Cold War, the perspective of listeners is relatively underexplored beyond the realm of letters found in institutional archives. Exploring the stories of those behind the radio sets by relying on oral history as method and by engaging with private collections in listeners’ homesteads can provide new insights into how internationalist registers of solidarity and friendship were crafted in the everyday through radio waves.

Radio Berlin International, or ‘The Voice of the German Democratic Republic’, as it was called by both those behind the microphones as well as the listening ears behind the radio sets, was established in 1959. Its Hindi Service, as part of the Southeast Asia Department, began its transmissions in 1967. While some of the Hindi show’s moderators were Indians, several presenters, journalists, mail-bag programme moderators, and staff were from the GDR and had learnt Hindi at East Berlin’s Humboldt University. Most of them had never been to India but joined the station to actively engage with the language and its native speakers, who were a continent away. Over the 23 years of its existence, the Hindi programme acquired popularity among hundreds of listeners and listeners’ clubs across suburban and rural Hindi-speaking parts of India.

As expressed by several listeners in interviews which I have conducted since 2018, the immense popularity enjoyed by Radio Berlin International (RBI) among Indian audiences rested on intimate ties of ‘warmth’, ‘love’, and ‘friendship’, which the station’s moderators forged with listeners. Several RBI listeners have painstakingly preserved their RBI memorabilia, letters, and GDR objects sent by RBI in the private space of their homesteads until today, even after over 33 years of the station’s closure in 1990. What explains this intimacy? How did ephemeral radio waves produce affective transnational ties of friendship across, and in spite of, Cold War ideological divides? How are these ties recounted today? I trace these questions by presenting the profiles of four avid listeners of the station, from Bikaner (Rajasthan), Gola Bazaar, Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh) and Madhepura (Bihar) and snippets of my ongoing conversations with them.

RBI’s Hindi Service

The Hindi programme began with a 20 minutes’ broadcast in 1967, which eventually became 30 minutes’ long and had three repeat telecasts every day. The show consisted of some centralized features like Tageskommentar, Aktuell, and Presseschau (daily commentary, news overview, and current affairs, in Hindi: Aaj ki Sameeksha), which were part of shows in all foreign language RBI broadcasts like those in Kiswahili, French, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, English, etc. Several regular weekly features included the Sportsendung (Sportsnews, Hindi: Khel-kud ke Samachar), Friedenssendung (Peace Reportage; Hindi: Kadam Badhao Aman Ki Khaatir, literally translated as- Take a Step forward towards peace), Das Land in dem Wir Leben (The Country in which We Live, Hindi: Wah desh jisme hum rehte hain and GDR Darshan). The show allotted a considerable part of its airtime to mailbag programmes (Hörerpost) such as Aapki Chitthi Mili (We Received Your Mail) and Aapne Poocha Hai (You Have Asked Us). The DX Programme was another platform of direct exchange through letters and reception reports between the presenters and the listeners. An international phenomenon since the 1920s, DXing refers to amateur listeners’ hobby of identifying and receiving distant radio or television signals, or making two-way contact with distant stations and informing them about the quality of reception through reports (DX is the telegraphic shorthand for distance or distant). DXers were sent a written acknowledgement of receipt of reports by radio stations in the form of QSL cards (acknowledgment cards). RBI had several dedicated DXers and DX clubs, as can very often be heard on the two hundred magnetic-tape recordings (1988–90) of the Hindi show, housed in the Deutsches Rundfunk Archiv (DRA) in Potsdam. From 1983 onwards, the Service started a new feature called Naye Mitron ke Patr (Letters from our New Friends) given the show had become highly popular among listeners and the station received many more letters than in the 1970s. This feature was especially introduced to address the letters of new listeners’ clubs of the show. Given that the radio station continued to exist until October 1990, one year after the fall of the Wall, the year 1989 saw the introduction of new features such as Berlin Diary, which captured the rapid transformations faced by the city after the re-unification of the two German states.

For most Indian listeners, it was East German voices which spoke to them in Hindi and the personal meticulous attention paid to their curiosities, questions, and messages that made the programme unique and a favourite.

Solidarity and Friendship in Madhepura, Bihar

Arvind Srivastava, a student of Russian history at the local university when he began listening to Radio Berlin International, is today a full-time writer and poet in Hindi. In the 1980s, Srivastava founded a radio listeners’ club called the Lenin Club in Madhepura, Bihar. Calling RBI his favourite station, Arvind recapitulates

I was stuck to RBI. The club’s main aims were to discuss the programme’s contents, inform oneself of world affairs, to critically comment on Cold War politics and also on India’s place as a Non-Aligned country in the world. We found a common voice against imperialism and market-driven capitalism. Our views found a commonality with the GDR. We were also aware of events taking place in countries like Mozambique, Chile, Angola, Vietnam, and Nicaragua. We saw socialism and anti-imperialism as the only solution to a world already torn by two recent wars.1Interview with Arvind Srivastava, en route Berlin to Bonn (DW), 31.01.2023.

Srivastava also held highly critical views of the Apartheid regime in South Africa. RBI’s shows thus provided him with a platform which resonated his own worldviews.

Srivastava was exhilarated to see these photos which he had sent to the station in the 1980s. Years after RBI’s closure (1990), they had travelled back to him through me in 2019 (figs. 1 and 2). It was a matter of pride for him that they had been carefully preserved for all these years by one of RBI’s moderators, Sabine Imhof, and that they had been in Berlin although he did not have any personal copies of the same anymore.

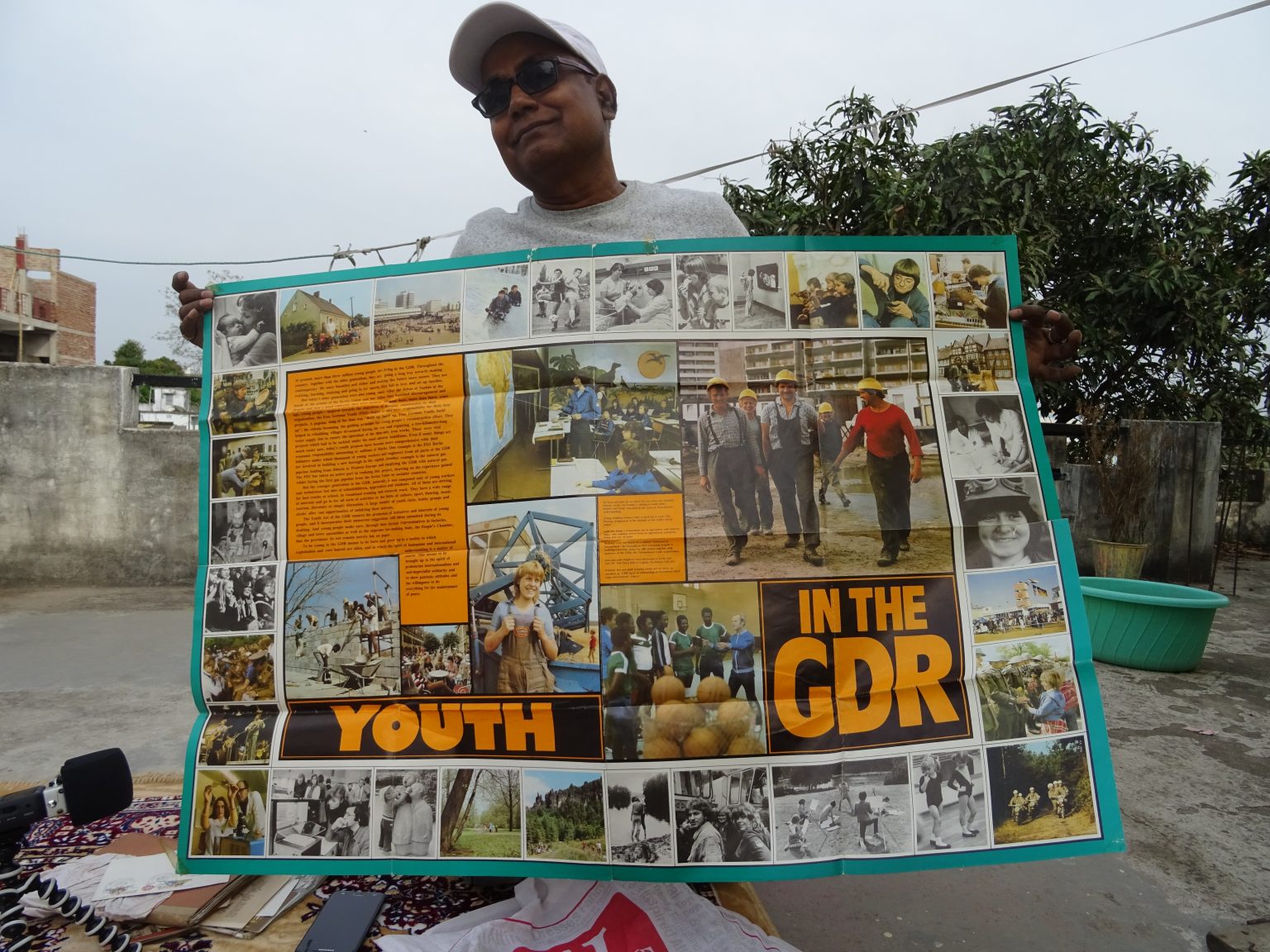

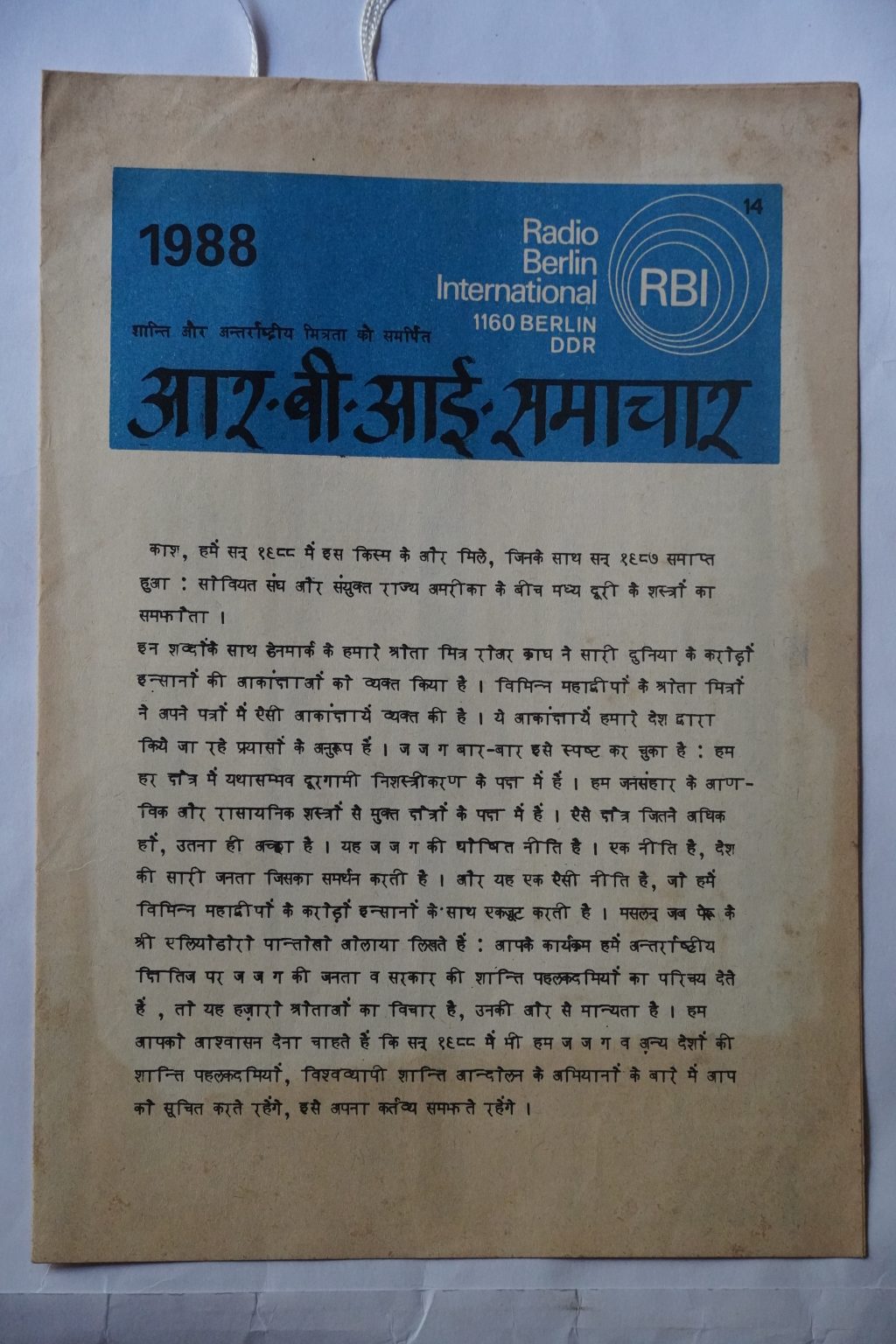

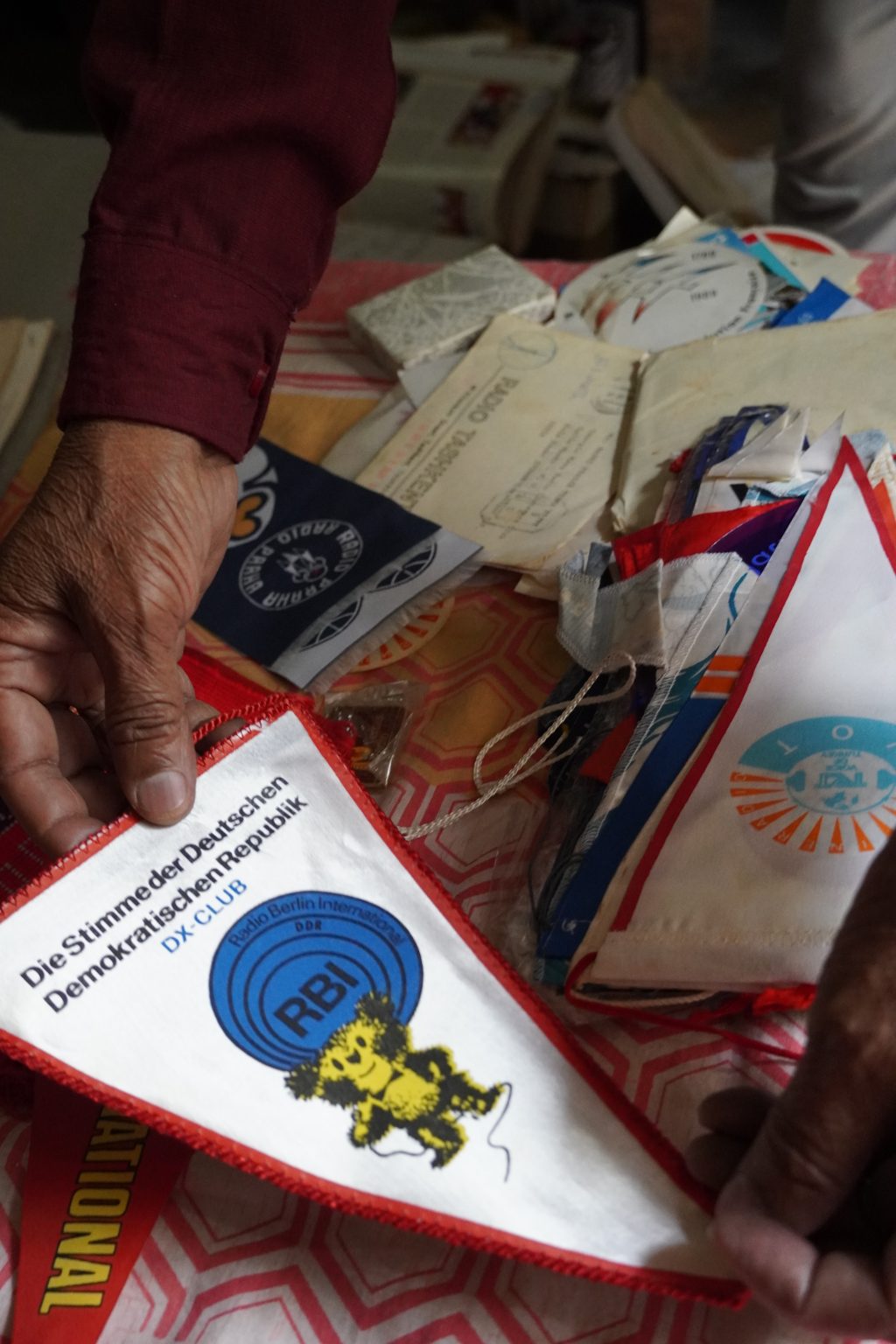

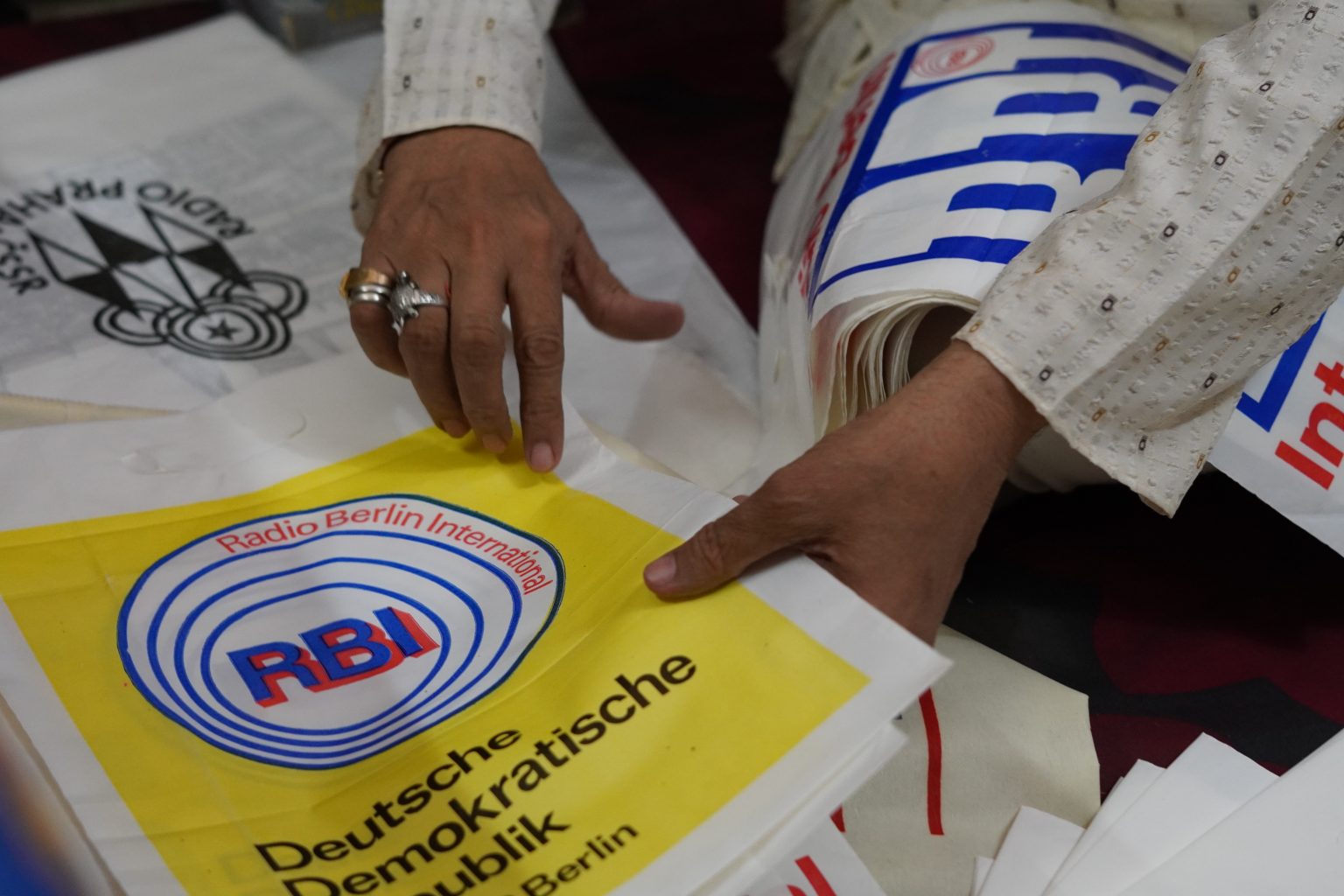

Among the memorabilia received from the GDR, which Arvind has safely stored in the attic of his homestead for years, one finds several RBI journals and pamphlets, QSL cards which he received on writing reception reports of the show, posters, pennants, letters, RBI peak-cap, and a half-destroyed photograph of the Funkhaus building at Nalepastrasse in East Berlin, from where RBI did its broadcasts (figs. 3 and 4).

While visiting his homestead in Madhepura to shoot for a documentary film on the entangled trajectories of RBI, its moderators and listeners between Berlin and Bihar, which I was directing at the time,2Documentary Film by Anandita Bajpai, The Sound of Friendship: Warm Wavelengths in a Cold, Cold War , https://www.projekt-mida.de/2050/filmankuendigung-thesoundoffriendship/, trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCVWosBrzYk Srivastava suggested that we visit his attic and take out all the GDR and RBI objects for a closer look. The act of documenting, partially digitalizing the published material, and photographing the radio-objects for the next three days on the rooftop of his homestead organically led us to the idea of organizing an exhibition, which would evoke memories of India-GDR Friendship and his personal ties to RBI.

What followed in the next days was a careful selection, sorting, and displaying of all memorabilia in his house and an exhibition which was officially opened with Arvind explaining the story of each displayed object to a room packed with visitors (figs. 5 and 6). The exhibition was in fact reminiscent of several such exhibitions which listeners like Arvind regularly organized when the radio station existed. These exhibitions were photographed, staged events, whereby listener clubs’ members performed solidarity with the GDR by displaying the materials sent to them in their club meeting rooms. Objects were made accessible for watching to local neighbourhoods in order to raise awareness about the radio station, its country of transmission, and its people’s everyday lives. I first accessed photographs of such exhibitions via the private collections of an RBI moderator, Sabine Imhof (mentioned above), who had been in regular contact with the listeners through letters between 1981–90. In these photographs, one sees objects that were sent to listeners carefully displayed like show pieces on tables and in vitrines. Books, journals, curtains in GDR flag colours, pamphlets, souvenirs, and pennants adorn the walls and tables of living rooms of club presidents’ homesteads, which were usually used as temporary exhibition spaces (for e.g. fig. 7).3For a detailed description of such objects and how listeners performed ‘love’, ‘friendship’ and ‘solidarity’ through and with them, see Anandita Bajpai, ‘Objects of Love: Remembering Radio Berlin International in India’, The GDR Tomorrow: Rethinking the East German Legacy, ed. by Elizabeth Emery, Matthew Hines & Evelyn Preuss (Oxford: Peter Lang, forthcoming 2023), 240–266 The exhibition in Srivastava’s homestead in 2019 was an attempt at recreating the affective mood of similar club activities in the 1980s.

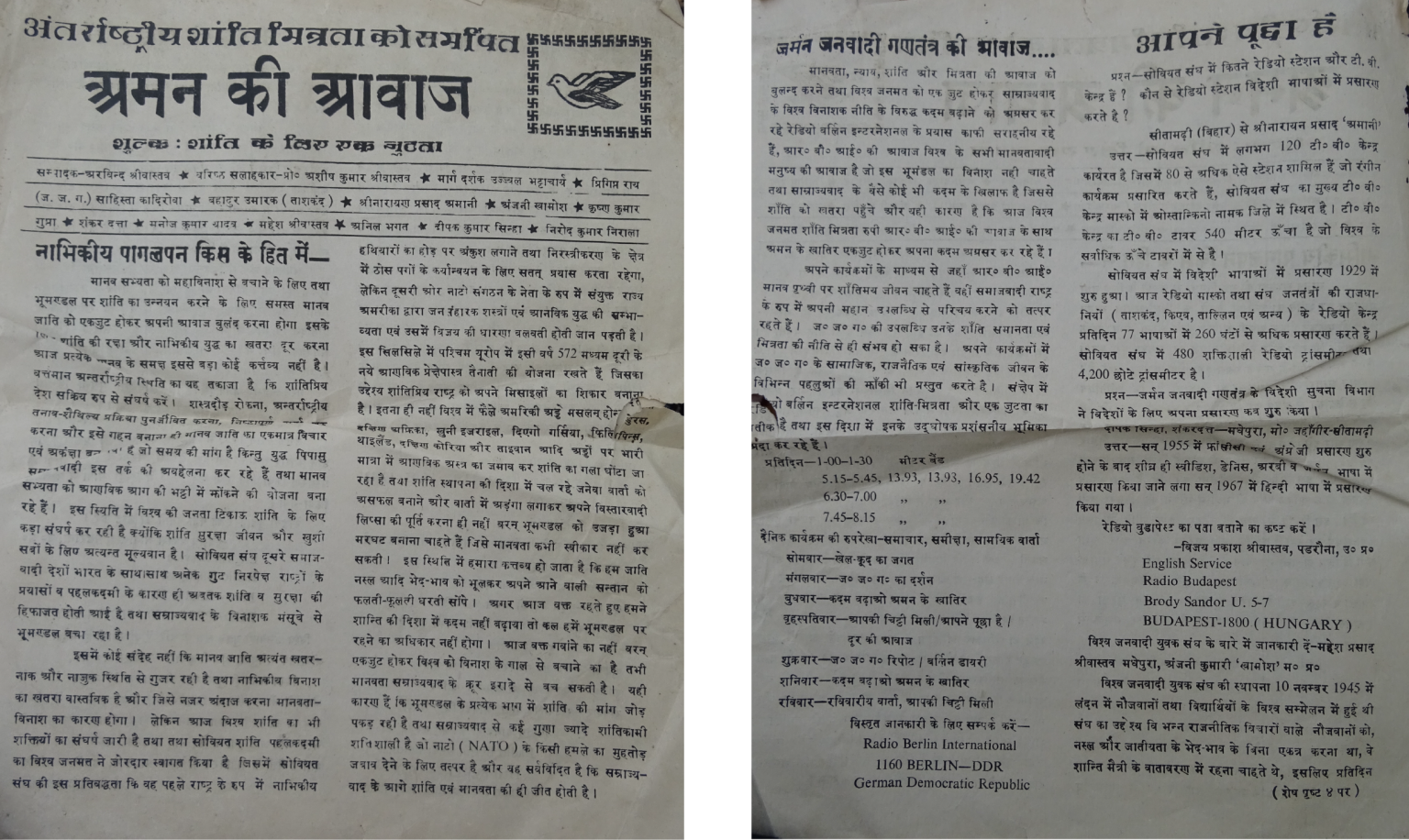

Arvind’s unflinching loyalty to the station’s message of solidarity and international friendship can also be traced in the fact that in 1983 he started a journal called Aman Ki Aawaaz (The Voice of Peace: Dedicated to International Peace and Friendship), financed and published entirely with personal resources. The journal not just gave details of RBI Hindi’s show, its telecast timings and the schedule of its programmes’ features, but also had several texts written on other topics such as the 2000th anniversary of Tashkent as the city of international peace and solidarity and critical essays against nuclear proliferation and the arms’ race. The journal thanks RBI’s Ujjwal Bhattacharya as one of its inspirational guides (figs. 8 and 9).

Recollecting his love towards his favourite show hosts, Srivastava recalls

We really wanted to meet the people working at RBI, whether it was Friedemann, Sabine or Marita, and the others like Ujjwal or Mahesh, or Wolfgang. At least, to see them once in person! It is like this: if you deeply worship someone in your heart, in the form of an idol, then you also want to meet them in person someday. Life becomes more meaningful if you can reach up to them. And there is one more thing: At the time radio did not just have a formal presence in my life. We also had a beautiful image of the people of the GDR: GDR citizens. If I saw any foreigner, I would wonder if he is from the GDR. And perhaps I could speak to him.4Interview with Arvind Srivastava, 27.03.2019, Madhepura, Bihar.

Intimacy and friendship through Objects in Bikaner, Rajasthan

A goldsmith by profession, Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar’s family (father and sons) specializes in fine-designing jewellery with silver, gold, and enamels. As a young radio listener in the 1980s, he has memories of long working days spent next to his father on the upper floor of his home, where the radio set’s sound was ubiquitous and the only accepted ‘foreign’ presence. Shielded away from everyday household life and other family members, this is the space where most of the designing work was done. Swarnkar vividly remembers fiddling with the radio knob and catching frequencies of foreign broadcasters such as Radio Tashkent, Radio Beijing, Deutsche Welle, Radio Praha, and Radio Berlin International on the first ever radio set in the house. The curiosity came when he first heard BBC’s Hindi Service and wondered if there were other radio stations in the world, which also had Hindi programmes. From 1982 onwards, Swarnkar became a committed listener of RBI, founded his own listeners’ club, and followed all its shows and repeat telecasts regularly. In his own words

I will tell you what was so special about RBI– for them it wasn’t only the club that was important, but the individual, the person. They took me very seriously as a person. And this is how their presenters were with every listener. It showed in the programme.5Interview with Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar, 02.04.2022, Bikaner, Rajasthan.

Over the years Swarnkar could recognize the voice of each moderator from the GDR. In his own recount, he felt intimate ties of friendship with these voices.

Listening to RBI was like an addiction and passion. Unlike most addictions, one didn’t harm anyone with such a hobby– a healthy passion– this is how I describe it. It gave me knowledge about the world. RBI was my favourite because each presenter had a personalized and proximate way of speaking to us listeners. Their voices would keep echoing in my ears long after the show was over. It is hard to express these feelings. Each one of them had a unique voice, tonality and way of speaking in Hindi. It was a unique experience to listen to these East German voices in Hindi.6Interview with Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar, 03.04.2022, Bikaner, Rajasthan.

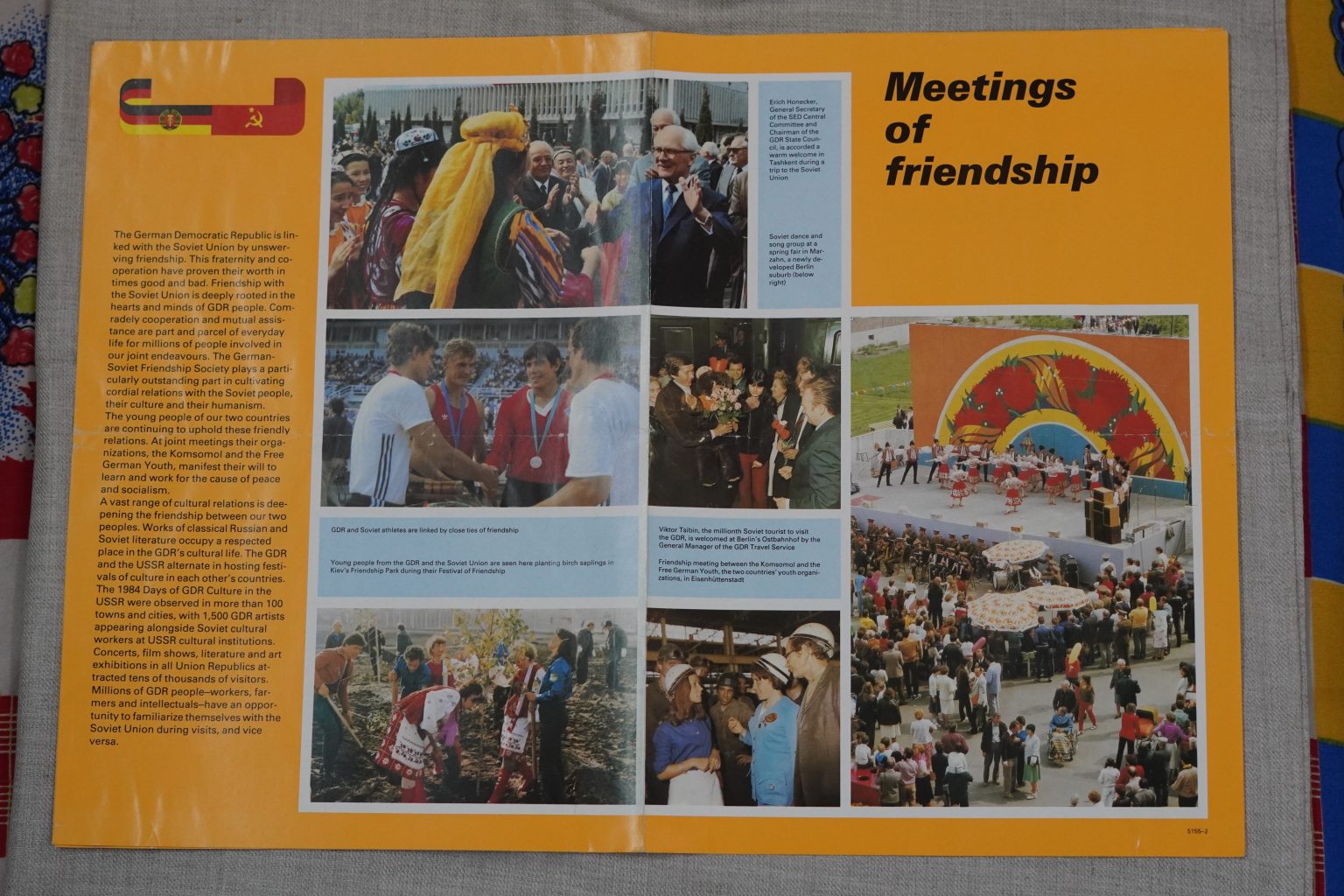

The show became a means for Swarnkar to inform himself of the GDR, its people and their everyday lives, and its urban and rural landscapes. In his homestead, in the same room, from where Swarnkar worked and heard RBI, today one finds several iron cupboards which are full of several objects that he received from the radio station almost 40 years ago. Among this plethora of items are for e.g. a GDR pioneer doll adorning an RBI scarf, a manual slide-viewer (Dia Betrachtor) with several slides that show GDR landscapes, plastic bags from RBI which are as glossy as they were when received, several pin badges, RBI peak caps, decks of RBI playing-cards whose wrappers have never been removed, GDR pennants, and every envelope of every letter Swarnkar received from the station (figs. 11–15).

These objects, which travelled from the GDR to Bikaner by registered post at the time were precious possessions which Swarnkar has meticulously preserved until today. In present times, they are a reminder of his ties of friendship with the country, its people, and most importantly, RBI’s East German moderators.

In 1999, Sabine Imhof travelled for the first time to India and, among others, she personally met one of her most ardent listeners in Bikaner, Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar. Rajendra’s attachment to radio-objects from RBI can be summarized in what Sabine tellingly recounted as a memory of her visit to his homestead

He showed me a part of the wall in his house where an RBI pennant had been hanging for years. This triangular patch had been saved from the impact of dust and humidity on the rest of the wall. I mentioned to Rajendra: “Of course, RBI does not exist anymore and neither does the GDR. It only makes sense that you have taken off the pennant from the wall”. To this he said- “I did not remove it because it didn’t make sense anymore to have it there, I removed it to save it from the wall. I removed it because I know that this will be one of the only memories I can keep of RBI.”7Interview with Sabine Imhof, 31.07.2018, Berlin.

GDR objects thus clearly served as ambassadors of friendship and forged intimate ties with RBI’s Indian listeners. They became material markers of radio’s pervasive presence in people’s everyday lives and years later, today they serve as instruments of recount in narrating listeners’ affective ties to the station and its host country.8I have historically unpacked the trajectories of such objects and their affective ties to radio listeners in Anandita Bajpai, “Material Lives of Cold War Radio-pasts in India”, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, forthcoming 2023.

Going Global from Gola Bazaar, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh

Based in a small township in eastern Uttar Pradesh, seventy kilometres away from the city of Gorakhpur is the township of Gola Bazaar, where Badri Prasad Verma ‘Anjaan’ and Shakuntala Verma have been avid listeners of RBI’s programmes since the inception of its Hindi Service in 1967. A hobby caricaturist and children’s short stories writer, Verma runs a general (all-purpose) store in his neighbourhood. His wife Shakuntala Verma has been a home-maker in the past, but now also assists their son in running another general store. In the 1980s, Verma founded the Swargiya Menu Shrota Club, a radio listeners’ club named after their eldest daughter, who died as a young child. The suggestion to name their club after their deceased daughter came from a moderator at Radio Beijing, Sun Ing, with whom the Vermas continued to have personal epistolary and telephonic contact until some years ago.

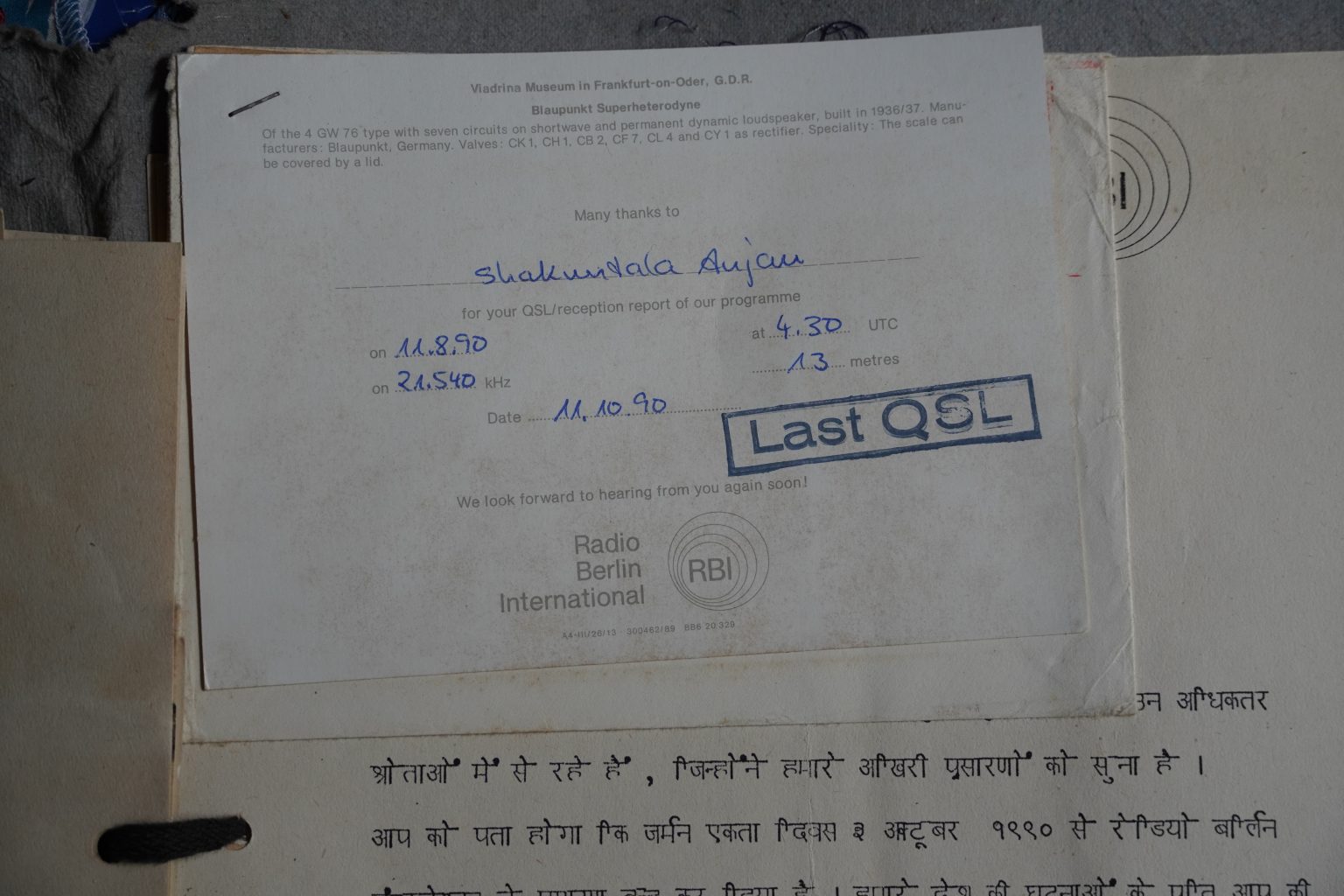

For the couple, it is a matter of extreme pride that they were one of the few listeners to have received the last QSL card issued by RBI (fig.17). While listening to RBI Hindi Service’s last broadcast from 02.10.1990, a copy of which (tape-recorded cassette) I had acquired from one of the show’s moderators (Marita Hoffmann) in Berlin in 2018, a teary-eyed Badri Prasad recounted how the show had helped him as a companion in difficult years. For him, the voices moderating the last show of the station reflected the pain that was felt by listeners all over India that day, knowing that their favourite radio show would never be aired again.

For Shakuntala and Badri Prasad there was no harm in listening to foreign broadcasters, which belonged to opposing ideological sides of the Cold War. As curious listeners, they were anything but passive receivers of Cold War ‘propaganda’. Among others, they also carefully followed the Hindi shows of Deutsche Welle, Radio Tashkent, Radio Beijing, Voice of America, BBC Hindi Service, Radio Moscow. However, they recounted how RBI and its presenters remained one of their favourites. The show touched their hearts and given the seriousness with which the station responded to their letters, their requests and their questions, they felt ‘recognized’ by the station. Both have safely maintained several folders with letters, QSL cards, pamphlets, journals, and newsletters (fig. 18) from the station until today. These and other objects that they received from the GDR via RBI, such as pennants, calendars and flags (figs.19, 20 and 21) have been preserved in the private space of their bedroom until today. Two of the features of the Hindi programme – Aapne Poocha hai (You have Asked Us) and Naya Daur Naye Prashn (A New Era, New Questions) – some 200 telecasts of which (1988–90) can be accessed in the form of magnetic tapes from RBI holdings of the Deutsches Rundfunk Archiv in Potsdam. These sound files are replete with questions, which were posed by the Vermas to the programme and which were duly addressed on the show. For Badri Prasad Verma, RBI did not just address his curiosities related to the GDR and the Cold War, but gave him an opportunity to insert himself in a global Cold War’s cultural politics. It enabled him to stage an internationalism from the very localized rural context of Gola Bazaar in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The show was a means to inform oneself of an ideological alternative – a perspective that was often different from what he heard on BBC, DW, or VOA. RBI’s programme, in his own words, allowed Verma not only to raise questions, but also to critically opinionate on world politics. Above all, the Hindi show’s features helped him compare and contrast everyday life of common citizens in both the GDR and India.

After reading our letters, and there were so many we sent them regularly, they (RBI) perhaps thought that these people in a small, disconnected village of eastern UP are so inquisitive. We had so many questions – about their country, its culture, its political set-up, its past, and, above all, its people. RBI enabled me to show that even if someone comes from such a tiny village, one can be part of the bigger, wider world.9Interview with Badri Prasad Verma Anjaan and Shakuntala Verma, 12.04.2022, Gola Bazaar, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Conclusion

In her recount of her experiences with reading listeners’ letters for almost nine years at the station, Sabine Imhof (also nicknamed the Postkönigin, the ‘Queen of the Post’) said

This is what impressed and excited me about my job from the very start — that they (the listeners) told us about their activities, their everyday lives, their problems, their achievements, that they asked so many questions. In spite of poor reception — it fluctuated! — they continued listening to us over the years. They told us about their political activism — that they sometimes organized protest marches and that they sent us pictures of all they did. So, if a club had built a new street in its village, they sent a proud picture of the new street with themselves standing on it with RBI banners that we had sent to them [smiles].10Interview with Sabine Imhof, 31.07.2018, Berlin.

RBI transmitted for the last time on October 2, 1990, after which the station was officially closed and Deutsche Welle became the only foreign broadcaster of the re-united German state(s). Three of RBI’s Hindi Division employees were re-appointed at DW whereas a majority lost their jobs overnight, with many pursuing a different professional trajectory thereafter. My ongoing conversations since 2018 with the moderators and listeners alike, however, testify that the station is anything but forgotten by either of the two sides. As I have argued elsewhere, objects that travelled from the station to listeners’ homes in India were a means to solidify bonds of intimacy, love, friendship, and solidarity.11Anandita Bajpai, ‘Objects of Love: Remembering Radio Berlin International in India’, Ibid. As markers of entanglements among Indian and GDR actors, they point to the material, affective registers produced by otherwise ephemeral radio waves. Their proximity to their keepers even today shows how radio was not just heard but how its waves continued to be ‘felt’ through things. Today these objects belong to listeners’ private collections and home archives which can be a hitherto unexplored rich source-base in documenting the station’s reception history as well as the history of India-GDR entanglements in the Cold War.

Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin

Principal Investigator, Crafting Entanglements: Afro-Asian Pasts of the Global Cold War

Leibniz Collaborative Excellence Project (2023–26) (K437/2022)

Footnotes

[1] Interview with Arvind Srivastava, en route Berlin to Bonn (DW), 31.01.2023.

[2] Documentary Film by Anandita Bajpai, The Sound of Friendship: Warm Wavelengths in a Cold, Cold War , https://www.projekt-mida.de/2050/filmankuendigung-thesoundoffriendship/, trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCVWosBrzYk

[3] For a detailed description of such objects and how listeners performed ‘love’, ‘friendship’ and ‘solidarity’ through and with them, see Anandita Bajpai, ‘Objects of Love: Remembering Radio Berlin International in India’, The GDR Tomorrow: Rethinking the East German Legacy, ed. by Elizabeth Emery, Matthew Hines & Evelyn Preuss (Oxford: Peter Lang, forthcoming 2023), 240–266.

[4] Interview with Arvind Srivastava, 27.03.2019, Madhepura, Bihar.

[5] Interview with Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar, 02.04.2022, Bikaner, Rajasthan.

[6] Interview with Rajendra Kumar Swarnkar, 03.04.2022, Bikaner, Rajasthan

[7] Interview with Sabine Imhof, 31.07.2018, Berlin.

[8] I have historically unpacked the trajectories of such objects and their affective ties to radio listeners in Anandita Bajpai, “Material Lives of Cold War Radio-pasts in India”, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, forthcoming 2023.

[9] Interview with Badri Prasad Verma Anjaan and Shakuntala Verma, 12.04.2022, Gola Bazaar, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh.

[10] Interview with Sabine Imhof, 31.07.2018, Berlin.

[11] Anandita Bajpai, ‘Objects of Love: Remembering Radio Berlin International in India’, Ibid.