An interview with Dr. Matin Baraki on the historical lessons from the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

23 May 2023

Interview: Matthew Read

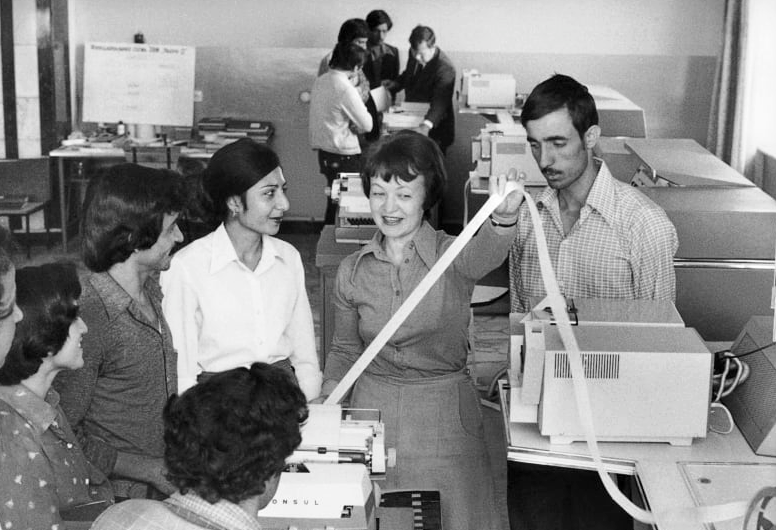

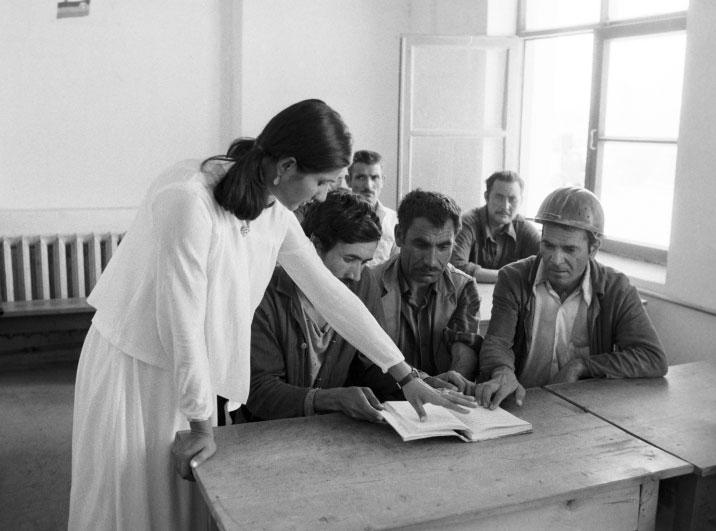

When the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) came to power in April 1978, it launched a massive literacy campaign and land reform to lift the country out of semi-feudalism and set it on a path of non-capitalist development. With the help of the socialist camp, the young Democratic Republic of Afghanistan brought tractors and combine harvesters to peasants who had previously relied on ox ploughs. It secured an education for those who had been systematically denied it and entrusted central societal functions to countless Afghan women.

But for the West, this national-democratic revolution in the Hindu Kush could not be allowed to set a precedent. Together with its allies, the USA soon set in motion an army of heavily armed and arch-reactionary “Mujahideen” to overthrow the PDPA government and establish an aggressive fundamentalist state on the Soviet Union’s southern border. Zbigniew Brzezinski, then National Security Advisor to US President Carter, later revealed the USA’s rationale: “What is more important in terms of world history? … A few Islamic extremists or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the Cold War?” 1Le Nouvel Observateur (N.O.), Paris, 15 – 21 January 1998, P.76. Zbigniew Brzezinski interviewed by Vincent Jauvert (own translation, MR).

In his recently published book, Afghanistan: Revolution, Intervention, 40 Jahre Krieg (“Afghanistan: Revolution, Intervention, 40 Years of War”), Dr. Matin Baraki revisits this history to show how the West plunged his homeland into decades of suffering. Baraki, who was himself active in the early clandestine circles of the PDPA, also reflects self-critically on the role of his former party, concluding that internal strife and ideological immaturity left too many doors open for the counterrevolutionaries and led to the PDPA’s increasing reliance on Soviet support. Yet Baraki draws on a range of sources to show that the Soviet intervention at the end of 1979 was by no means an act of aggression, but rather desperately sought-after military assistance to repel the onslaught of foreign-backed Islamists.

As part of our examination of the socialist camp’s anti-imperialist strategies in the 20th century, we first asked Baraki about the PDPA’s conception of national democracy and non-capitalist development. We then discussed how these strategies were concretely implemented in the Afghan context, before contrasting the role of socialist states with that of the West. The interview is accordingly divided into five sections.

I. The People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan and its political strategy

Can you start by telling us about your background? You grew up in Afghanistan during the monarchy and initially worked in Kabul. How did you become politicised?

I was born in 1947 in a small Afghan village and grew up there. My father was a poor peasant and illiterate, like my mother. After his father died when he was just five years old, my father was taken out of school and put to work. He suffered under this for his entire life and so made it his mission for me to attend school. I later started an apprenticeship as a precision mechanic, but my father later fell ill when I was 16 and died shortly afterwards. I then had to try to feed my family of nine, so I dropped out and started working as a semi-skilled mechanic in a steel factory.

It was the era of the monarchy. There were neither political parties nor trade unions. But I became politicised there in the factory: We workers organised ourselves and tried to win a wage increase through a strike. The colleagues delegated me as spokesperson for the strike at that time and, of course, I was then the first to be sacked by the management. After six months of unemployment, I found a job producing teaching material for a technical training school. Through this job, which was linked to the Ministry of Education, I was lucky enough to be able to attend further education courses after work to complete my secondary school diploma.

I then became a primary school teacher but also continued my studies. My goal was to study in the Soviet Union, so I applied to the Polytechnic University in Kabul, which was built by the USSR. There I worked as a technical assistant at the Faculty of Natural Sciences.

It was at this time that the monarchy was overthrown. Everyone was euphoric. In Afghanistan, people had believed that the king was the shadow of God: since God is permanent, his shadow must also be permanent. But now the shadow was gone. That in itself was a great success, even on this psychological level.

And did you have contact with the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) at that time?

Yes, of course. But the party was still illegal. We met secretly in tea houses to organise the party work. The meetings took place there or at some comrades’ homes. We always arrived at the meetings at 10- or 15-minute intervals so that no one noticed what was going on.

How did you end up doing your doctorate in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG)?

As I said, I wanted to study in the Soviet Union, but the Faculty of Natural Sciences where I worked had a partnership with the University of Bonn. As part of this partnership, I received a scholarship to study there in 1974. But when I arrived, I was told that I could only do an internship and not a degree. That was out of the question for me because such an internship would be superfluous in Afghanistan. So, I turned it down and started studying at the University of Marburg at my own expense. I had to work during the semester and holidays to finance everything. On top of that, I had to fight for the residency permit. That was at the end of 1979, beginning of 1980, just when the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan had begun. The FRG then allowed me to stay for the time being, but I was not allowed to leave the small town of Marburg. I actually wanted to go to the GDR for further education, but I was ultimately threatened with this expulsion and had to finish my studies.

As the war in Afghanistan worsened, my professor in Marburg recommended that I do my doctorate there and said to me: “By the time you finish the doctorate, your country will surely be at peace. Then you can go home.” I liked the idea at the time. But eventually I was finished with my doctorate and Afghanistan is still not at peace today.

Returning to the party, in your book you mention that the PDPA consisted mainly of members of the intelligentsia. Can you describe its class character in more detail? And, against this background, also the split in the party that took place shortly after its founding?

The party was founded in 1965 in illegality. This founding meeting took place in the house of Nur Muhammad Taraki [1917–1979] in Kabul and Taraki was elected as the party’s first general secretary. The membership and especially the leadership consisted almost entirely of urban intellectuals with petty-bourgeois characteristics. There were virtually no opportunities for political education in Afghanistan at that time. This meant that the party had only vague ideas about Marxism, and this was, of course, one of our weaknesses. It was evident in the split in the party that occurred two years after its founding.

The immediate cause of the split was the struggle for leadership positions. There were in reality few positions to distribute because the party was still working illegally, but everyone wanted their share. Two groups quickly formed. The first gathered around Taraki and Hafizullah Amin [1929–1979] and was called the Khalqi.2Named after the first central newspaper of the DPDA. The second group formed around Babrak Karmal [1929–1996] and was called the Parchami.3Named after their own newspaper, which this group published weekly. The former was radical, while the latter group around Karmal pursued a scientific strategy.

The big debate revolved around the party’s strategy and the question was: what do we do if there is a revolution in Afghanistan and we have the chance to come to power? The Khalqi said we would start constructing socialism straight away. The Parchami, on the other hand, said, no, this will be a national democratic revolution. And because it will be a national democratic revolution, we must make alliances, even with the national bourgeoisie. We even have to support the national bourgeoisie so that it invests in the country and so that the working class and the workers’ movement can emerge. That, in short, was the ideological point of contention between the two factions.

Did the Khalq-faction deny the necessity of the non-capitalist path of development?

No, they did not deny it. Neither faction denied the strategy of non-capitalist development. But the Khalqi claimed that the party should play the leading role. The Parchami agreed but argued that it was still necessary to form an alliance.

In the book I briefly show how the same question was disputed in the Comintern during Lenin’s lifetime.4This refers to the debate on “the national and colonial question” at the Second Congress of the Communist International (1920). Comrade M. N. Roy from India and Comrade Sultan-Zade from Iran argued that in the former colonies the Communist Parties alone should take power. Lenin said no, that would be wrong because these countries are mired in backwardness. A broad, national, anti-imperialist alliance must be formed first. And this discussion was then repeated in the PDPA.

As a side note, in Afghanistan it was assumed that 5% of the labour force was employed in industry. I worked in a factory and knew my colleagues well: every noon after lunch the muezzin called, and they all went to pray. The Afghan workers were mostly craftsmen who had fled from the villages to the cities. Most of them were illiterate and had no idea of socialism, let alone class consciousness.

“So, to speak of a working class in Afghanistan was a false perception. It was pure theory.”

So, to speak of a working class in Afghanistan was a false perception. It was pure theory; it was only in the minds of some comrades. They talked about the working class, recognized that only 5% of the working masses were proletarians, and somehow that should be enough for a socialist revolution, for a dictatorship of the proletariat.

How did the Parcham-faction understand the role of the PDPA in a national democratic state? Was it to be a workers’ party leading an anti-imperialist front or was it to be a cross-class people’s party representing the whole national movement?

The PDPA called itself the vanguard of the working class. Karmal also clearly referenced this concept in his speeches. He said we are the party of the working class, but in our strategy, we want to create a broad alliance. The PDPA will play the leading role and give the orientation, but on the way, we will need partners. And the partners must in fact be the entire Afghan people, from peasants and workers to the national bourgeoisie. The Parchami also argued that we need to support the national bourgeoisie so that we can free ourselves from the comprador bourgeoisie and foreign capital.

One last question about the party, before we go into more detail about the strategy of non-capitalist development: What links did the PDPA have with the international communist movement and the socialist camp? The military officers who helped overthrow the monarchy in 1973 and then also carried out the Saur Revolution of 1978 were members of the PDPA and were even trained in the Soviet Union. How did this come about?

There were secret party circles in the military, just as I described our civilian circles. They organised their own groups. And yes, many officers were trained in the Soviet Union. But first concerning the PDPA’s links to the international communist movement: This connection was actually fostered by the Tudeh Party of Iran. The communist movement did not initially recognise the PDPA because it was so divided. Indeed, the internal strife was so severe that the party split in two just a couple of years after its founding. The communist parties refused to recognise these two factions and demanded that they must first come to an agreement. The Tudeh Party was given the task of mediating between the factions to negotiate a unification. The Iranian comrades managed to play this political role. When the party came under pressure just before the Saur Revolution, it reunited nolens volens. But in general, we were a sister party of the international communist movement. The party’s representatives took part in all the major meetings of the movement; they were present everywhere. At meetings of the CPSU or SED, and even at the party congress of the German Communist Party (DKP [the communist party in West Germany]) in Mannheim in 1978.

The ties between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union were always very close, even well before the Saur Revolution. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) was the first country to recognise Afghanistan’s independence from British colonial tutelage in 1919. It also immediately annulled all unequal treaties with Afghanistan and established qualitatively new relations. When I addressed Afghan-Soviet relations as part of my doctoral thesis, I printed the letters between Lenin and the then King Amanullah. They are almost love letters… the terms and vocabulary with which they address each other about the friendly relations between the Afghan and Russian people – it is phenomenal!

II. The path of non-capitalist development in the Afghan context

Can you describe socio-economic conditions in Afghanistan in the early 1970s? And how was the strategy of non-capitalist development supposed lift the country out of this situation?

Afghanistan was an agricultural country. More than 80 % of the population lived in the countryside. Although they made up only 5 % of the rural population, the big landowners had more than 50 % of the land. In the north of the country, they made up only 2% of the rural population, but owned 75% of the land. Subordinate to these large landowners were poor and landless smallholders and agricultural labourers. There were also some state-owned agricultural enterprises, but the vast majority of agricultural production was private.

In the cities there was light industry, some of which was owned by foreign capital. There was a wool-processing factory from Wuppertal (Federal Republic of Germany), for example. But mainly this light industry was run by national capital, that is, by Afghan capitalists. In addition, state-owned enterprises operated in heavy industry. Where I worked, for example, was a steel factory that belonged to the Ministry of Industry and Mining. It was built and supported by the Soviet Union – my foreman was in fact a Soviet specialist.

That was the economic situation in a nutshell. As for the class structure, I have already mentioned that only 5% of the working population was employed in the industrial sector. The rest were mostly peasants or agricultural labourers. And now, starting from this analysis, the question arises: how do we develop the country? How can a country in which feudal and semi-feudal conditions prevail be lead to socialism? For us it was clear that there is only one way, namely the non-capitalist way. So, we reject capitalism, but recognise that we will need allies. One of the most important allies, as I said earlier, was national capital: we need to support national industry and the commercial bourgeoisie in order to develop the productive forces in Afghanistan.

But above all, we must eliminate large-scale land ownership through a land reform, and this is what we initiated after the Saur Revolution. The properties of the major landowners was to be distributed among the peasants and agricultural labourers. Yet we would leave the previous owners enough land to live a good life, provided they cultivate it themselves. That is, they were no longer allowed to exploit the other peasants on their land.

The other central task was to overcome illiteracy. In Afghanistan, over 90% of the population could neither read nor write. The figure was even higher for women.

Those were the three tasks: Literacy, land reform and support for the national bourgeoisie within the framework of a national alliance. In this way, we would pave the way to socialism in Afghanistan. Taken together, these measures were to accelerate the process and economically underpin our socialist orientation. Through literacy and the education of the people, the subjective conditions for a later socialist revolution were to be established.

What does it mean in concrete terms to support the national bourgeoisie and the commercial bourgeoisie? Is that not in fact promoting capitalist development?

This discussion had also taken place in the Comintern since the beginning. There are a number of examples where parties that emerged from the colonial struggle and subsequently took power were unwilling to form alliances. They were afraid that by supporting the national bourgeoisie, the latter would become stronger and one day displace us. But Lenin said we need not be afraid of this because we still hold the power. We are in government, we have the military, and so on. We are the ones giving the direction and guidance because we are at the head of the national movement. The national bourgeoisie is to be incorporated within the framework of this strategy that we have developed. So the fear was unfounded.

The consequence of this fear was that the strategy of non-capitalist development was often not implemented. And the parties that came to power became dictatorial because of that. Let’s look at Algeria: Algeria was a model country for the Third World. We read the Algerian constitution in Afghanistan like the Bible or the Koran. It was a central role model for us. But what did the Algerians do after they took power? They did not take the national bourgeoisie and the non-capitalist path towards socialism seriously. They installed a dictatorial regime.

One has to create robust structures in order for the party and the system to continue to develop after the loss of individual leaders. For this, one must take the strategy of the non-capitalist path seriously and implement it accordingly.

To briefly address another aspect: For a national industry to develop in an agricultural country like Afghanistan, it was necessary to support the national bourgeoisie. You cannot make a revolution with peasants alone. Our objective was a socialist revolution, but a socialist revolution can only be led by the working class. And we also wanted to become a real workers’ party – we were, as I said, a party of intellectuals with petty-bourgeois views. The workers have to come from somewhere. Only through national capital can the working class emerge and develop into a class in its own right. That was a core idea behind this strategy.

III. The implementation of these strategies and the support of the socialist camp

Let’s turn to the events in Afghanistan in the 1970s to examine these strategies concretely. Five years before the Saur Revolution, PDPA-affiliated military officers overthrew the monarchy. They gave power to Mohammed Daoud, former prime minister [1953–63] and brother-in-law of the deposed king. Why did they do this? Was it an attempt to build the national democratic state with Daoud at the helm?

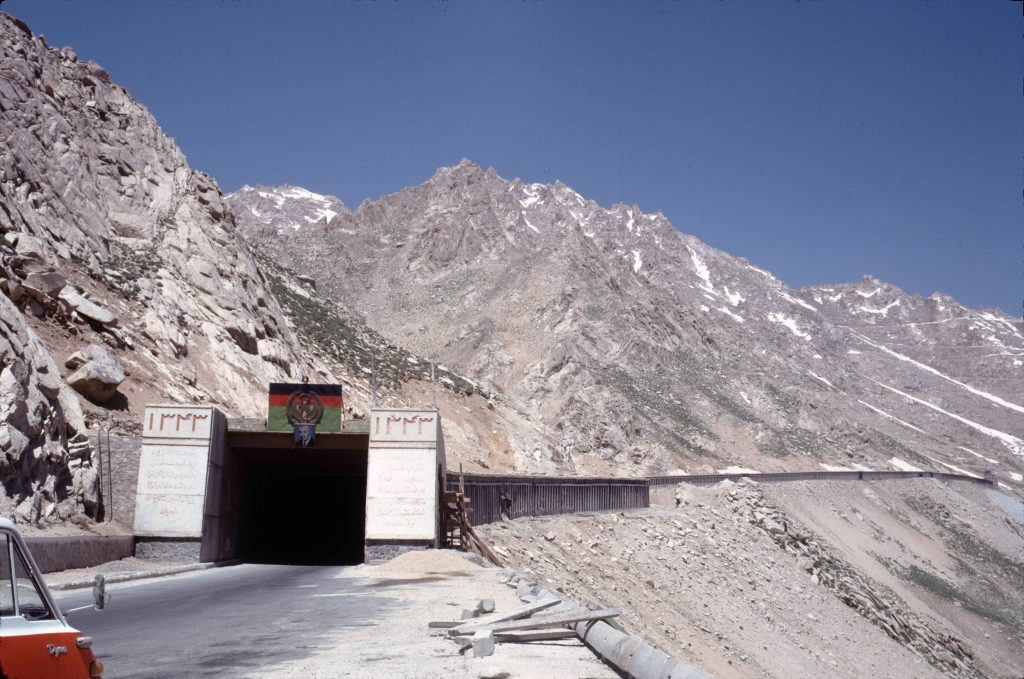

Daoud had good contacts with both the military and the Soviet Union. To provide a little more context: Afghanistan joined the Non-Aligned Movement after World War II. The Afghan government initially turned to the US for military and economic aid, but US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles demanded that Afghanistan join the Baghdad Pact in return. The Afghans refused and turned to the Soviet Union, which offered help without conditions in relation to the Warsaw Pact. Thus began the educational, economic, and military cooperation between Afghanistan and the USSR after the war. This all started during Daoud’s tenure as prime minister and was intensified by him. A lot was done in agriculture and industry, along with important infrastructure projects. Many roads were paved and, of course, the vital Salang Tunnel was built. Such projects were very popular with the Afghan people.

So Daoud enjoyed great popularity and was known throughout the country. The PDPA, on the other hand, had hardly made a name for itself at the time. Moreover, it was Daoud who had initiated this coup; the military only helped him execute it. That is why he was appointed president afterwards.

Yet Daoud proved to be dictatorial, he failed to bring about the promised reforms, showed pro-imperialist leanings, and even tried to eliminate the PDPA. How did these developments pave the way for the Saur Revolution in 1978?

These dictatorial tendencies did indeed develop over the years. Daoud’s historic mistake was to launch open repression against the PDPA leadership in the spring of 1978. He had Taraki and Karmal arrested and wanted them executed. It was announced on the evening news that the party leadership would be held accountable and possibly liquidated. The PDPA-affiliated military intervened to save the party, otherwise it would have been destroyed along with the leadership. So, Daoud provoked the military uprising that took place on 27 April 1978, which we later called the Saur Revolution. The military freed the PDPA leadership from prison and handed power to them — three days later the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was declared.

In the book I speculated about the internal discussions in the party at this time. Once again, it was about the different strategies of the two factions. The Parchami held that the objective and subjective conditions first had to mature before a revolution could take place. The Khalqi around Taraki and especially Amin thought that the PDPA simply had to win over enough military officers to bring about a military uprising. Amin explicitly worked towards this end. Conflicts subsequently arose among the members of the Central Committee who were responsible for contacts with the military. Amin repeatedly spoke out in favour of a military uprising, while the Parchami rejected this as adventurism. Amin was thereafter to be dismissed from his position.

As I formulated in the book, Amin could well have been behind the assassination of rivals and one of the government’s ministers at this time in an effort to provoke Daoud into launching open repression against the PDPA. In this way, Amin would have had a justification for carrying out a military uprising. I base this theory on his speeches and a history book he had commissioned. Amin wanted an uprising – he was merely looking for a pretext. Daoud’s historic mistake was to give him just that by arresting the PDPA leadership.

As I said, Karmal and the Parchami wanted to wait until the objective and subjective conditions were ripe for a popular uprising. Only in a revolutionary situation can one lead a revolution. They rejected Amin’s approach as adventurism, and they were right: the struggle against Daoud’s people lasted two days – the military uprising could have gone wrong.

How did the international communist movement react to this development?

The parties were of course surprised. But I assume that the leadership of the CPSU knew what was going on in Afghanistan through reports from the KGB. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union was the first country to recognise the DR Afghanistan and to warn all other countries that there must be no interference in the country’s internal affairs.

Despite these unfavourable circumstances that accompanied the founding of the DR Afghanistan, the PDPA swiftly initiated profound reforms. How did these measures develop in the cities and in the countryside? What difficulties did they encounter?

In the first phase, several reforms went well. Within six months, for example, 1.5 million people learned how to read and write. But there were also mistakes, particularly in the land reform. The major landowners were dealt with too brutally and clumsily.

Afghanistan was still characterised by tribal structures. There were peasants, for example, who did not want to receive land from their tribal leader or cleric. So, the land redistribution was then partly carried out through coercive measures. That was a mistake. One could have said: Well, if you don’t want to do it this way, then establish an agricultural cooperative. Then not only the landlord will have the say, but all of you.

“The party and especially those of us who were young wanted to develop the country overnight. We did not have the revolutionary patience that is required under such circumstances.”

But we were too impatient. This had to do with the fact that the situation in Afghanistan was incredibly dire. In 1971/72 there was a drought and almost 2 million people died. The party and especially those of us who were young wanted to develop the country overnight. We did not have the revolutionary patience that is required under such circumstances. We made many mistakes that ultimately left doors open through which the counterrevolution had easy access.

This is a crucial aspect of non-capitalist development in the former colonies, I would say. The persistence of pre-feudal relations such as tribal structures made the tasks of national construction much more complicated. There were similar difficulties in Mali, for example, where the contradictions between the different classes in the countryside were initially masked by patriarchal and village community structures. This greatly hindered revolutionary initiatives in the countryside. So, land reform in the former colonies should be understood as a qualitatively different task from those in the Eastern European people’s democracies.

That’s right. And here, of course, it is essential to have a capable, experienced, and patient party.

A German professor once asked me why the Afghan process failed. I replied that if the Afghan revolution had succeeded, then the social science of Marxism would have been refuted, because we as the PDPA had all the “infantile disorders” that have ever existed in the communist parties, as Lenin put it. We had all of these “infantile disorders” – petty-bourgeois sectarianism was widespread among us. And we were inexperienced. Imagine it: The party was just 18 years old when it took power. We had no political education, no experience of democracy or revolution. To give such a party power and the mandate to carry out a revolution, that is a huge task.

At the end of December 1979, Amin was overthrown and Karmal’s group took over. They stopped some reforms that had gone too far. Some other reforms were slowed down and others continued. The results were mixed. By the time of the Soviet intervention, Afghanistan was like the child that had fallen into the well. The mistakes of the Taraki government and especially the Amin government had made the situation extremely difficult. Amin, after all, killed 12,000 party members — he was like an Afghan Pol Pot. Karmal and the Soviets were then tasked with rescuing this child from the well. We were up to our necks in the mire. Slowly, mistakes were corrected, and the situation improved, but the problems did not diminish – support for the counterrevolution had increased massively.

Can you briefly describe the extent and character of the socialist camp’s assistance to the DR Afghanistan during these years?

Previously, Afghanistan had only oxen and donkeys. For the first time we saw machines like tractors or combine harvesters. Agricultural cooperatives were set up to enable farmers to borrow these machines or to buy food very cheaply in the cooperative shops.

Hardly anyone had had a fridge or a television. The Soviet Union and other socialist countries sent masses of supplies to us, and one could buy them very cheaply. When my son went through the list of things we were to receive, he joked to me, “Father, the only thing missing from this list is a wife!” Everything else was listed on it. Additionally, thousands of scientists and specialists came from the socialist countries and thousands of young Afghans went to these countries to receive training in all kinds of disciplines.

As far as the GDR is concerned, the SED gifted the PDPA an entire printing press. Before that we had books that were crooked and slanted, you could hardly read them. And the GDR gave us one of the most modern printing works around. They also sent a group of comrades to Afghanistan to advise on how to build a popular front. These comrades had worked in the GDR’s National Front and could share their experience. This was at the time when the PDPA had begun to correct its past mistakes – Amin had been ousted and Karmal’s group was now trying to build the National Democratic Alliance. The comrades from the GDR were supposed to support them.

So, there was massive support from the socialist countries in many different areas, especially in the education of young Afghans.

IV. The counterrevolutionaries and their foreign patrons

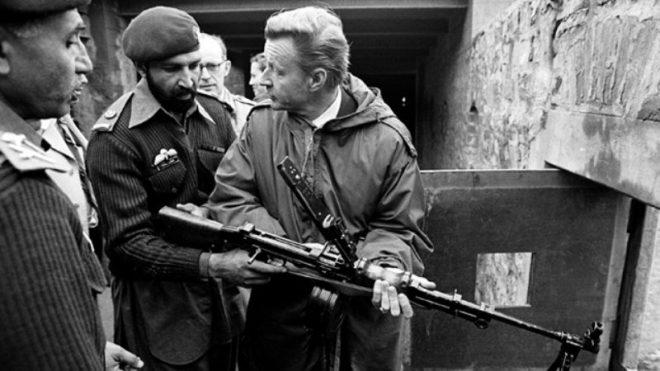

Let us now turn to the PDPA’s struggle against counterrevolution and the related Soviet intervention in Afghanistan that began at the end of December 1979. In your book, you cite various sources to show that the US started supporting Islamic extremists in July 1979 at the latest, six months before the Soviet intervention. Can you briefly describe the background to the intervention?

We must begin with the Treaty of Friendship between the DR Afghanistan and the USSR. On 5 December 1978, this treaty was signed by both sides. The fourth article contained a military component: it stated that in the event of an attack on the USSR, Afghanistan was obliged to assist the USSR and vice versa. So, if Afghanistan was invaded by a foreign country or if external forces attempted to overthrow its government, the Soviet Union was obliged to “take appropriate measures”. This was also in line with Article 51 of the UN Charter.5Article 51 states: “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.” Both sides were thus legitimised under international law and obliged to provide mutual assistance, including military support. This is a vital component of the relations between the USSR and the DR Afghanistan to begin with.

In the book I quoted the then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He said that Afghanistan could not be allowed to set a precedent. If the Afghan revolution was successful, it would inspire revolt across the whole region. This would threaten not only the strategic interests of the USA but also “their” oil. So, Kissinger concluded that everything possible had to be done to ensure that this national democratic revolution failed. This was in fact a declaration of war on the part of US imperialism and its NATO allies against Afghanistan. And they thus set this war in motion and prosecuted it until 1992, when the successor to the PDPA capitulated.6In July 1990, the PDPA was renamed Hesbe Watan (Party of the Homeland) and abandoned Marxism-Leninism for social democracy. According to Baraki, after the resignation of General Secretary Mohammad Najibullah in March 1992, the leadership around Foreign Minister Abdul Wakil decided to transfer power to the counterrevolutionaries – that is, there was no seizure of power by the counterrevolutionaries in 1992, but rather a capitulation.

They quite literally destroyed the country. It was the CIA’s largest covert operation – together with the Pakistani intelligence service, they brought some 35,000 extremists from over 40 Islamic countries to Pakistan, where they were trained, equipped, and then smuggled across the border into Afghanistan. Every year, 65,000 tonnes of weapons were given to the Mujahideen. By the end of 1983, they had succeeded in destroying 1,800 schools – that was half of all schools in Afghanistan – and 130 hospitals. Girls’ schools in particular were deliberately targeted. The total damage amounted to about 50% of the country’s total investment over the previous 20 years.

The People’s Republic of China was also involved, by the way. It sent Uighurs from Xinjiang to Afghanistan to fight against us on the side of the Islamists with the support of the CIA. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the most radical Islamist and leader of the Islamic Party “Hezb-i-Islami Afghanistan”, was the CIA’s favourite mujahid. I have quoted a letter from him in which he asked for experts from “the friendly countries of the USA and China” to train “our mujahideen” in the use of the weapons supplied by them.7See Matin Baraki: Die Politik der VR China gegenüber Afghanistan.

http://www.zeitschrift-marxistische-erneuerung.de/article/666.die-politik-der-vr-china-gegenueber-afghanistan.html The mujahideen had in fact received Chinese-produced Katyusha rocket launchers and had to learn how to operate them. These Katyusha were broken down into smaller pieces, brought across the border on donkeys and camels and handed over to the Islamists for deployment against us.

Was this foreign support ultimately decisive for the success of the counterrevolution in Afghanistan?

No, the decisive factor was Gorbachev. Afghanistan was Gorbachev’s first gift to the West. When it was decided to withdraw Soviet troops from the country, the commander of the Soviet army, Boris Gromov, said that this withdrawal was not militarily necessary. They had achieved great successes and had large parts of the country completely under control. Gromov argued that the country would now begin to stabilise. Indeed, Kabul was more peaceful at that time than it had ever been before or since. It was possible to enjoy a normal life in the capital city. The withdrawal was a political decision, and it was taken by Gorbachev. He gifted Afghanistan to the West, just as he later gave the GDR away.

“Gorbachev gifted Afghanistan to the West, just as he later gave the GDR away.”

By the end of the 1980s, the Islamists were in fact almost finished. This is shown by the fact that the Afghan military fought without the Soviet forces for three more years. There were three major operations by the counterrevolutionaries from Pakistan against the DR Afghanistan and they were all crushed — without any Soviet troops at all!8This refers to, for example, Jalalabad (March 1989), Kabul (October 1990), the city of Khost in Paktya province (March 1991) and Jalalabad (July 1991). At one point in the book, I quoted an editorial from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung [a West German newspaper] in January 1990. They were frustrated that the Afghan mujahideen had been unable to “capture a single significant city in Afghanistan”.

If the Soviets had stayed and continued their support, the country would have indeed stabilised.

What were the consequences of the intervention for the Soviet Union and the PDPA? Was there a significant loss of trust or prestige among the Afghan population?

The PDPA made a total of 21 pleas to the USSR to send military troops.9The appendix to Baraki’s book documents some of the minutes of these meetings and communications. The Soviets repeatedly refused: We cannot and will not do that. They said, we will support you economically, militarily, propagandistically, ideologically, politically, and diplomatically — but you have to fight for yourselves. Yet the PDPA was unwilling.

One has to understand: NATO wanted this intervention. Brzezinski, US President Carter’s National Security Adviser from 1977 to 1981, said that they wanted to turn Afghanistan into a Vietnam for the Soviets. OK, the USSR consistently refused to send troops, so what changed? There were two key developments.

Firstly, the Soviets wanted to wait and see if NATO was going to actually deploy Pershing II missiles – that is, first-strike weapons – in Western Europe. The Soviets tried to prevent this but failed. The mastermind behind this action was then Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Helmut Schmidt [Social Democratic Party of Germany]. And on 12 December 1979, it was decided to station Pershing II missiles in Western Europe. Secondly, around the same time, a military operation was being planned for January or February 1980 in which armed Islamists were to be parachuted into Kabul to overthrow the government. The Soviets knew that this was coming.

These two developments led the CPSU to decide to send a special military unit to Kabul – they made this decision immediately after the so-called NATO Double-Track Decision was announced. In his first statement to the Soviet newspaper Pravda, Brezhnev said that they wanted to prevent a second Chile.10In September 1973, the socialist government of the Unidad Popular in Chile was overthrown in a coup supported by the USA. In addition, there were other strategic considerations: The USSR could not allow a fundamentalist Islamic state to be established by foreign powers right on their Southern border. So, they intervened.

Of course, this put great strain on the Soviet Union. Its reputation in Afghanistan was damaged. Yet through their massive support, they were able to partially make up for it. As I mentioned, the Soviets provided a great deal and trained thousands of young people. In the final phase of their support, women made up 80 % of the labour force in the education and health sectors. The illiteracy rate among Afghan women had always been incredibly high, but after the socialist camp’s support, 80% of important societal positions were managed by women. Significant progress had thus been made in a very short period – you cannot forget that.

V. Historical lessons from the DR Afghanistan

What are the historical lessons from DR Afghanistan and its party, the PDPA?

After the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan at that time, a group of young students in West Germany invited me to talk about the situation. One comrade said to me: “There are 100,000 Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan now, why not send another 100,000 and then just build socialism?” I replied to her that socialism cannot be built by the military: “The military has the task of protecting us from outside attacks and from counterrevolution. Socialism must be built by the people, by the workers.” The working class is the mainstay of socialism. And in Afghanistan, it was exactly this that what was missing. We Afghans, during the leadership of Taraki and Amin, understood the situation just as simplistically as this West German comrade had.

We lacked an exact analysis of the class relations. We had not genuinely assessed the conditions in Afghanistan. Just take the example of the land reform: we should not have tried to simply expropriate and redistribute the land of the landowners when they were at the same time tribal leaders and clerics. We should have sat down with the landowner and his tribe and said: “We want you to be better off. Not just only the tribal leaders and the clerics, but all of you. How do we do that?” Instead, we took a sectarian approach. Our view of the world was marred by our own fantasies; we were too far removed from Afghan reality. This is what one can learn from the history of the DR Afghanistan and the PDPA.

[1] Le Nouvel Observateur (N.O.), Paris, 15 – 21 January 1998, P.76. Zbigniew Brzezinski interviewed by Vincent Jauvert (own translation, MR).

[2] Named after the first central newspaper of the DPDA.

[3] Named after their own newspaper, which this group published weekly.

[4] This refers to the debate on “the national and colonial question” at the Second Congress of the Communist International (1920).

[5] Article 51 states: “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security.”

[6] In July 1990, the PDPA was renamed Hesbe Watan (Party of the Homeland) and abandoned Marxism-Leninism for social democracy. According to Baraki, after the resignation of General Secretary Mohammad Najibullah in March 1992, the leadership around Foreign Minister Abdul Wakil decided to transfer power to the counterrevolutionaries – that is, there was no seizure of power by the counterrevolutionaries in 1992, but rather a capitulation.

[7] See Matin Baraki: Die Politik der VR China gegenüber Afghanistan. (The PRC’s policy towards Afghanistan.)

[8] This refers to, for example, Jalalabad (March 1989), Kabul (October 1990), the city of Khost in Paktya province (March 1991) and Jalalabad (July 1991).

[9] The appendix to Baraki’s book documents some of the minutes of these meetings and communications.

[10] In September 1973, the socialist government of the Unidad Popular in Chile was overthrown in a coup supported by the USA.

The interview was conducted on 10 May 2023 and has been lightly edited for readability.