Day 2 – Vietnam: David triumphs over Goliath

Day 3 – Guinea-Bissau: “Violence is the essential instrument of imperialist domination”

Day 4 – Mozambique: FRELIMO’s armed struggle against Portuguese brutality

Day 5 – Cuba: The language of friendship

Day 6 – Chile: “Venceremos!”

Day 7 – USA: “The other America”

Introduction

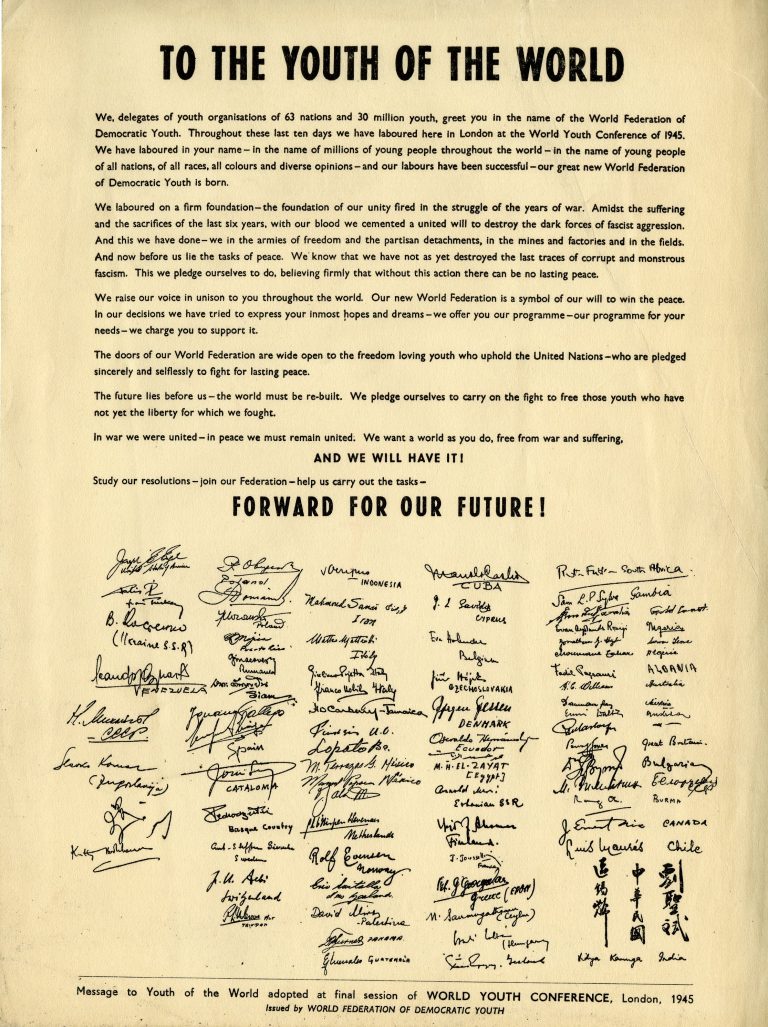

“To eliminate all traces of fascism from the earth. To build a deep and sincere international friendship among the peoples of the world. To keep a just lasting peace.”

This was written in the founding declaration of the World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY), adopted by 437 delegates from 63 countries, representing over 30 million youths worldwide, at the first World Youth Conference in London in November 1945. Only three months earlier, the Second World War had ended with the devastating atomic bombing of Japan by the USA. The world lay in ruins. This young generation confronting devastation, displacement, and bereavement joined together across borders on an unprecedented scale to prevent the youth of tomorrow from enduring such suffering again.

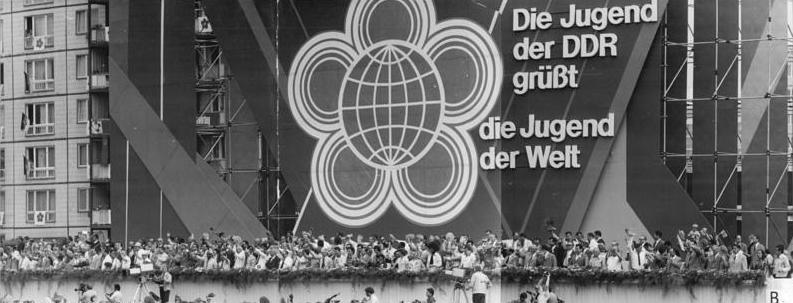

A central instrument to develop unity in the spirit of peace and anti-fascism were the World Festivals, which were inaugurated in Prague in 1947. They continue to be organized by the WFDY to this day. In July 1973, exactly 50 years ago, the 10th edition of the World Festival began in Berlin, the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). From 28 July to 5 August, 8 million participants, including 25,600 guests from 140 countries, took part in a broad programme of over 200 political and 1,000 cultural events under the slogan “For anti-imperialist Solidarity, Peace, and Friendship”.

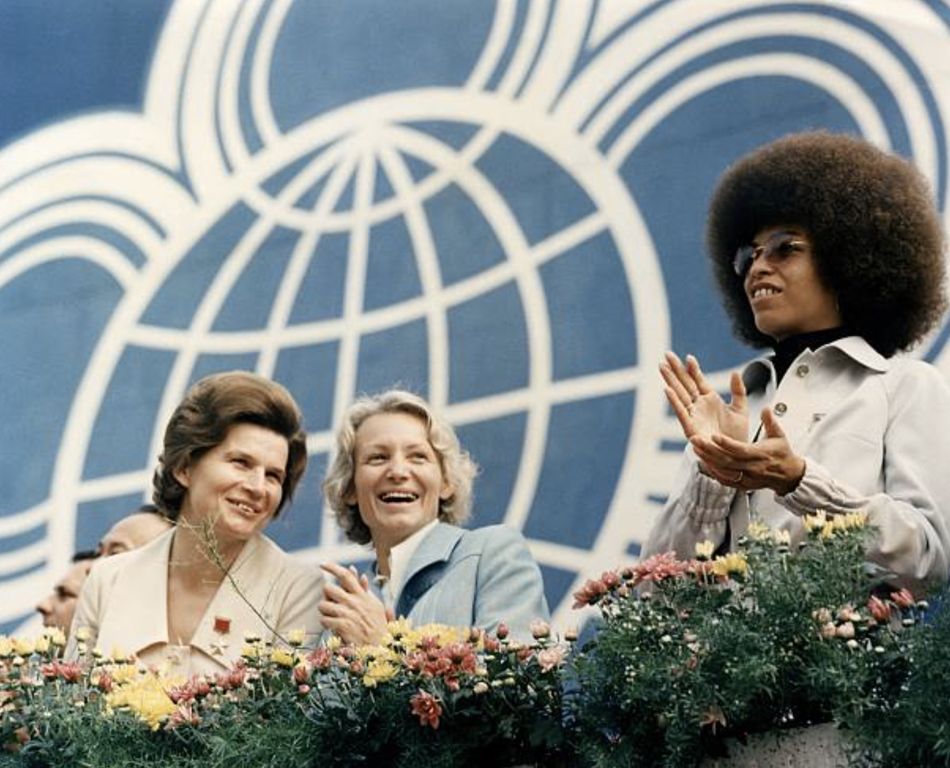

The X. World Festival took place at a time of general upsurge in the struggle against imperialism and for socialism: The Vietnamese people had wrested decisive defeats from the world’s most powerful military power, the USA. The struggles against Portuguese colonial rule in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were advanced resolutely. In 1970, the Unidad Popular under Allende’s leadership had won power in Chile. A worldwide solidarity campaign was able to generate immense pressure for the acquittal of Angela Davis. The “Basic Treaty” between West Germany and the GDR put an end to the former’s openly aggressive policy towards the latter. The international recognition of the GDR opened up scope for development and created economic relief. The 1973 World Festival became an assertive beacon for progressive forces around the world. The struggles in Vietnam and Chile took a prominent place in the festival programme. Support for the Palestinian struggle was reaffirmed by the presence of PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat. Angela Davis and Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, were guests of honour at the festival. Inti-Illimani, Miriam Makeba, Dean Read and many other artists could be seen and heard on the 95 festival stages. The festival left an optimistic mood and strengthened the forces of national liberation and socialism in their struggle. Yet the fascist coup by Pinochet in Chile on 11 September 1973, just a few weeks after the festival, would deal a harsh and brutal blow to this mood.

With short articles on the festival delegations from Vietnam, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Chile, USA, West Germany, and Cuba, we want to sketch a picture of the X. World Festival and the political context of the time. For that, we have dug deep into various media sources of that time, particularly GDR newspapers. To this day, the many thousands of participants in the World Festival have lasting and impressive memories of these nine days in Berlin. The strong and global unity of the youth in the struggle for peace, against fascism and imperialist oppression lost its strength with the collapse of the socialist camp in 1989/90. Yet the programme, which was already adopted in 1945 in the Peace Oath at the founding of the WFDY, remains relevant:

“We pledge that we shall remember this unity, forged in this month, November 1945. Not only today, not only this week, this year, but always. Until we have built the world we have dreamed of and fought for. We pledge ourselves to build the unity of the youth of the world. All races, all colours, all nationalities, all beliefs. … FORWARD FOR OUR FUTURE!”

Vietnam: David triumphs over Goliath

Vietnam was at the forefront of the anti-imperialist struggle in 1973. Despite being the target of the largest aerial bombing campaign in history, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV) had brought the US military to its knees. In January 1973, the USA signed the Paris Peace Accord and thereby suspended all combat operations in Vietnam. By March, all US combat troops had been withdrawn. The fighting now continued between Vietnam’s communist forces and Washington’s proxy government in South Vietnam, which still maintained a considerable superiority in terms of the number of troops, tanks, and armoured vehicles.

By the time the Vietnamese delegation arrived in Berlin for the X. World Festival in July 1973, more than one million PAVN and LASV troops and two million civilians had been killed. The task ahead was to rebuild the country and liberate the remaining territory from the US client state. The first day of the World Festival was thus dedicated to “Solidarity with the peoples, youth and students of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia – now more than ever!” There were mass meetings, film screenings, Southeast Asian artist exhibitions, song, and dance of the peoples of Indochina, and even a cross-country run through the city “dedicated to solidarity with the people of Vietnam”.

At the “Solidarity Centre” in Berlin’s famous TV-Tower, Erich Honecker met with the Vietnamese delegation. Vo Thi Lien, a young girl who had survived the Mỹ Lai massacre in 1968, presented Honecker with a ring made of metal from a downed US bomber. He told her: “We will complete the work of those who were murdered. … We will always stand by Vietnam, together with the Soviet Union and the socialist countries and all anti-imperialist forces.” When greeting the rest of the delegation, Honecker informed them that the GDR had decided to write off all loans granted to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and that they should be considered as gratuitous aid.

Less than two years after the festival, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam liberated Saigon and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was founded in July 1976. Close relations were maintained between the new government in Hanoi and Berlin.

Guinea-Bissau: “Violence is the essential instrument of imperialist domination”

For Portuguese colonialism, Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde archipelago off its coast were an administrative and logistical hub for the slave trade in West Africa until the early 19th century. The Salazar regime in Portugal, anxious to assert its colonial claims even in the face of the strengthening independence movements, feared for the loss of the colony. An independent Guinea-Bissau would most certainly weaken Portugal’s grip on its other colonies, Angola and Mozambique. Salazar thus waged an obstinate and bloody war against the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) and the people of Guinea-Bissau: The crimes of the Portuguese secret police PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado) ranged from their infamous concentration camp in Tarrafal in Cape Verde to the napalm bombing of the small coastal country.

“Violence is the essential instrument of imperialist domination,” said Cape Verdean revolutionary leader and co-founder of the PAIGC Amílcar Cabral. He concluded “that there is not, and cannot be national liberation without the use of liberating violence by the nationalist forces, to answer the criminal violence of the agents of imperialism.” His guerrilla strategy proved effective, as did his foresight as a Pan-Africanist: under Cabral, the PAIGC won, bit by bit, sovereignty over first individual areas and finally the entire country. In the areas that were gradually liberated with the help of military equipment supplied by the socialist states, new political structures were established and the transition to an independent country was prepared. Achieving this depended largely on the general and political education of the population, which the PAIGC organised in schools it had built in the liberated areas.

This process was in full swing when Cabral was assassinated in January 1973. The members of the PAIGC who were studying in the GDR at the time wanted to return home immediately, but the party demanded that they stay and finish their education. Thus, a former student from Guinea-Bissau also told us that he had to experience his country’s long-awaited independence, which was declared on 24 September 1973, from afar while he successfully completed his studies in the GDR. The spirit of optimism during the X. World Festival, the expressions of solidarity with Guinea-Bissau and the progressive forces of Portugal were promising expressions of a coming change. After the independence of Guinea-Bissau, the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974 finally ended the Portuguese colonial wars in Mozambique and Angola.

Mozambique: FRELIMO’s armed struggle against Portuguese brutality

The territories of modern-day Mozambique had been colonized by the Portuguese for over 400 years. What had initially started as coastal settlements, trading posts, and forts in the 16th century had, by the beginning of the 20th century, expanded into a comprehensive and highly exploitative settler economy in which land was controlled by a minority of Portuguese colonizers and natives were subjected to forced labour. In the face of racist colonial policies, coercive agricultural cultivation and work allocations in mines, guerrilla groups of exiled Mozambicans began cropping up in neighbouring states. The Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) was formed in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in 1962 by various exiled groups and took up arms against Portuguese colonialism in 1964. In this endeavour, FRELIMO received extensive military and political support from the socialist states. The GDR, for example, began supplying the FRELIMO with military and medical aid in 1967 and launched training programmes for Mozambican militants and students at East German schools.

Although outmanned and outgunned, FRELIMO fighters used guerrilla tactics to chip away at the resolve of the Portuguese troops over the next decade. By 1969, FRELIMO had liberated one-third of the country, largely in the rural areas in the North, where FRELIMO had established a strong base of support by launching campaigns to increase peasant access to education and healthcare and construct agricultural cooperatives free from Portuguese control. While originally founded as a pluralistic national front, the FRELIMO increasingly moved towards Marxism-Leninism by the end of the 1960s, becoming one of the leading revolutionary forces in Africa.

Nine years into the Salazar regime’s war against FRELIMO and several months prior to the X. World Festival in Berlin, Portuguese commandos razed the Mozambican village of Wiriyamu to the ground, slaughtering all 400 of its civilian inhabitants. The PIDE secret police planned and guided this “Operation Marosca” against the families of the village for allegedly sheltering guerrilla fighters. The massacre in Wiriyamu exhibited the true nature of Portugal’s self-proclaimed “civilizing mission” in Africa. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), of which Portugal is a founding member, lent the Salazar regime de facto support through arms supplies and political exoneration on the world stage.

The East German press had been covering FRELIMO’s struggle and, in particular, the Wiriyamu Massacre extensively in the months prior to the X. World Festival. The FRELIMO delegation was thus greeted with great respect and solidarity, participating in cultural events, political discussions, and debates on military strategy with other militants. Sérgio Vieira, who headed FRELIMO’s Culture and Education Department, led the delegation, stating, “Our delegation spared no effort to come to the X. World Festival. Some of us have walked for more than a month. This festival is an important demonstration of the anti-imperialist struggle of the progressive youth of the world, a landmark of their struggle for peace and friendship.” Within a year, the Carnation Revolution led to the overthrow of the Estado Novo regime in Portugal and after Guinea-Bissau also to the liberation of Mozambique and Angola.

Cuba: The language of friendship

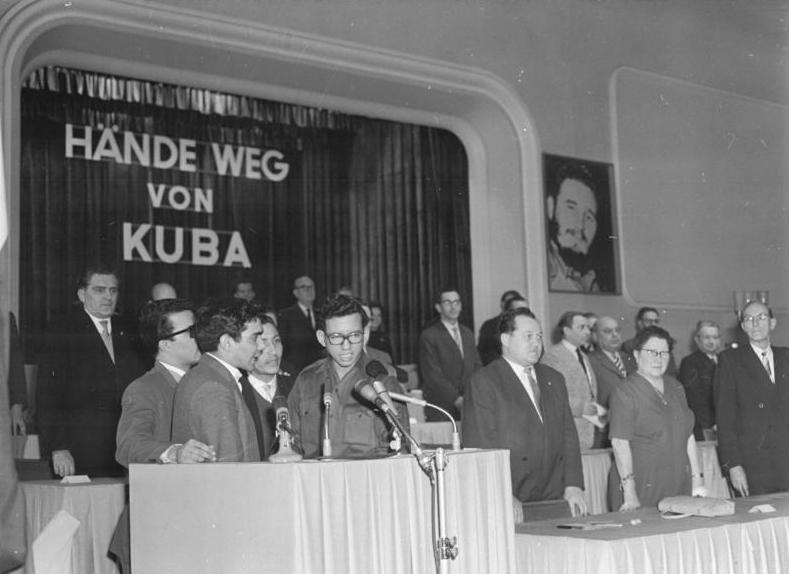

In 1959, the revolutionaries around Fidel Castro and Che Guevara succeeded in overthrowing Fulgencio Batista’s regime in Cuba. The USA thereby lost one of its suppliers of raw materials, not least due to the subsequent nationalization of industry and land reform. The US blockade imposed as a result, which continues to this day, had a massive impact on the economy of the small island nation, which, in its immediate proximity to the United States, repeatedly became a focal point of the Cold War, such as during the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 or the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1963.

In accordance with their capabilities, the socialist countries set out to support Cuba economically. The GDR, for instance, imported tropical fruits and sugar, built industrial plants on the island, sent experts, and trained Cubans in the GDR. In 1972, Cuba became a full member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In the same year, Fidel Castro visited the GDR. There he met the workers of the Leuna chemical plant in Halle, whose expert teams had been constructing an ammonia factory in Cuba that had been originally planned by the U.S. but abandoned after the revolution.

During his visit, Fidel presented the GDR leadership with a map of Cuba. It included an island bearing the name of the former leader of the Communist Party of Germany, Ernst Thälmann, who was murdered by the fascists in 1944. The renaming of the island was a symbolic act by which the Cuban government expressed its “sincere interest” in further developing “relations of cooperation and mutual understanding” with the GDR. Fidel justified the choice of name with the historical role that both Thälmann had played for the global workers’ movement and that the island, located at the Bay of Pigs, had played for the defeat of the “aggression of the imperialists” in 1961.

As if to underline this, one of the fighters who successfully repulsed the American invaders at the Bay of Pigs accompanied the Cuban delegation to the X. World Festival in 1973: the national hero Fausto Díaz had lost both legs in battle and, at a rally in Berlin, spoke to the young people present from all over the world from his wheelchair: “This encounter also proves that, in the long run, the enemy will never be able to stop the advance of our ranks.”

In addition to the Secretary of the Young Communist League of Cuba, Manuel Torres, the Chinese-Cuban revolutionary and president of the League of Pioneers, Juan Mok, also accompanied the Cuban delegation. During a Chile solidarity meeting he optimistically addressed the Chilean delegation: “When the socialist revolution entered Latin America with our victory, the (…) imperialists decided that there should not be a second Cuba in the Western Hemisphere. They miscalculated!”

The Communist Party of Cuba’s Granma newspaper summed up the World Festival in Berlin: “The streets of this city are populated by young people who, despite the diversity of their language, have found a common ground, that of friendship.”

Chile: “Venceremos!”

In 1970, the Unidad Popular, a coalition of left-wing forces, won the elections in Chile and Salvador Allende became president. The euphoria over this victory reverberated in the socialist states, even though the situation on the ground remained tense. The fact that the resource-rich country wanted to take an independent path and thereby have sovereignty over its extractive industries – which had been dominated by US and European companies for decades – was not accepted by the West. Allende’s measures, such as the nationalisation of the mining sector, provoked those who stood to lose the most: the old Chilean elites, large landowners, foreign corporations, and their governments. From the beginning, the reactionary threat hung over the progressive alliance like a dark shadow. Attacks on and even the assassination of representatives of the popular front were not uncommon.

In view of the fragile situation in her homeland, Gladys Marín, then general secretary of the Chilean Communist Youth, emphasised in an interview: “The Solidarity Meeting for Chile here in Berlin had a significant international weight because it took place at a very critical time for my homeland.” She led the 60-strong Chilean delegation, which was made up of a cross-section of the organisations represented in the coalition government, to the X. World Festival in the DDR. Chile was one of the defining themes of the festival, where solidarity with the Unidad Popular resounded again and again and Venceremos reverberated through the crowd.

But the certainty of victory experienced a bitter setback. Shortly after her return from an extended trip as a representative of the new government that stretched as far as Asia, Marín was forced into hiding after Pinochet’s coup on 11 September 1973. In West Germany, the coup was met with joy and trade with the Pinochet dictatorship subsequently boomed. In 1974, exports from the Federal Republic to Chile increased by over 40 percent, imports by 65 percent. Franz-Josef Strauß, long-time member of the government in West Germany and chairman of the Christian Social Union (CSU), commented cynically on the coup at the time: “In view of the chaos that had reigned in Chile, the idea of ‘order’ suddenly sounds sweet for the Chileans again.”

Marín, now in exile, repeated her journeys to fraternal countries. This path led her through the GDR again, among other places, where many exiled Chileans had found refuge, including the later president of Chile, Michelle Bachelet. The events in Chile deepened the solidarity movement in the DDR. Immediately after the coup, people gathered spontaneously on the streets of Berlin and expressed their support for the Unidad Popular. The Solidarity Committee of the DDR set up the Chile Centre in Berlin, which coordinated fundraising and aid for almost 2,000 Chilean immigrants. International solidarity campaigns were launched, including one devoted to the release of Luis Corvalán, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Chile. The Chilean delegation’s visit to the World Festival earlier that year had consolidated the solidarity movement, which would prove key in the years following the 1973 coup. As Marín told the enthusiastic youth who received her at the festival: “We have come to Berlin with great expectations. (…) The festival will further strengthen our common worldwide struggle against imperialism.”

USA: “The other America”

The US delegation to the X. World Festival consisted of almost 300 youths. It was led by Angela Davis, who was a familiar face internationally and to the youths in the GDR. Only one year prior had she been released from prison in a highly politicized trial entrenched in anti-communism and racism. The socialist states had played a key role in the campaign to set Davis free, including the GDR’s campaign in which East German school children sent one million roses to the imprisoned Davis in the form of postcards.

The delegation led by Davis represented “the other America”, as it was referred to in the GDR: the working class, the Black and Indigenous liberation movements, the anti-war groups, and other anti-imperialist political forces. It included eleven members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), whose occupation at Wounded Knee had been brutally suppressed by the state military, exhibiting the continuity of the genocide against the indigenous Americans. There were also Innuit and Asian American delegates, Hispanics, and African Americans, who had only recently achieved the desegregation of US schools, despite the harassment and even murder of many of their leaders by the FBI, CIA, and racist vigilantes.

Just prior to the X. World Festival, Vietnam had been able to expel US troops from the country. Several members of the US delegation were ex-soldiers, now turned anti-war activists. In Berlin, they met with the fighters from the Vietnamese delegation in a moving fraternal gathering that ended with a commitment to campaign for the release of the 200,000 Vietnamese fighters still imprisoned by the US’s proxy government in South Vietnam. As Davis said, “I want to assure my brothers and sisters of Vietnam that we in the US now see the struggle for the release of the 200,000 as the most important task. More than 200 revolutionary and progressive organisations are involved in this struggle. I myself feel a special responsibility in this cause, as I also owe my freedom to an international mass protest.”

Davis underscored the importance of travelling abroad to socialist states with youth from the capitalist West: “I believe that the US delegation represents the best part of the youth of the United States. … [Many] had previously been exposed to false propaganda about the GDR and had also had little contact with the socialist countries. They were surprised when they came here, because the realities they saw here had nothing to do with the propaganda they had been exposed to for so long.”

West Germany: A delegation of détente

More than 800 participants from over 40 youth and student organisations from the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) took part in the X. World Festival in Berlin. Among them were representatives of Protestant and Catholic youth, such as members of the Junge Union, the youth wing of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). The broad composition of the West German delegation reflected the changed relations and strategy on the part of the FRG towards the GDR.

In 1951, when the third edition of the World Festival took place in Berlin, the FRG still relied on repressive measures to prevent West German youth from participating. The police used force to stop 450 young people from Hamburg on their journey. Werner Tiegel, leader of the youth group “Geschwister Scholl”, was driven into the Elbe River by the police and drowned before them. Initially, the so-called “Hallstein Doctrine” had determined the foreign policy of the FRG. With this doctrine the FRG prescribed its refusal to recognise the GDR, insisted on its claim to be the sole representative of the German people, and sanctioned third countries if they established diplomatic relations with the GDR. West Germany’s goal was to isolate the GDR internationally.

By the 1970s, the West had adopted a new strategy in an attempt to bring about “change through rapprochement” (Wandel durch Annäherung). With the “Basic Treaty” ratified in July 1973, shortly before the X. World Festival, the FRG recognised the GDR under state law (but not under international law). This opened up new international scope for the GDR to conclude treaties with other countries; in September 1973, it joined the UN. The GDR had no illusions regarding the character of the Western states, as Honecker made clear in 1976: “Peaceful coexistence does not equate to class peace between exploiters and exploited. Peaceful coexistence means neither maintenance of the socio-economic status quo nor ideological coexistence.” A certain normalisation of the relationship was an important condition of development of the socialist camp, especially for the GDR. The “peace”, however, remained deceptive. Neither West Germany nor the rest of NATO abandoned their position towards socialism. Now, more subtle influence and the development of economic dependence were undermining socialist society in the East. It is in this context that the participation of such anti-communist forces as the Junge Union in the summer of 1973 should be understood. In their luggage they carried megaphones and some 20,000 pamphlets in which they agitated “to defend human rights, freedom of travel and a free development of culture”. Their content failed to impress the participants of the World Festival; at this moment of the 20th century, their arguments appeared weak and hypocritical.

As an audible compromise, the politically mixed delegation was accompanied by the folk song “Horch, was kommt von draußen rein” (Listen, what’s coming in from outside) as they entered the World Youth Stadium. The socialist part of the delegation, from organisations such as the Socialist German Workers’ Youth (SDAJ) or the Marxist Students’ Federation (MSB-Spartakus), meanwhile, participated extensively in the festival programme, taking part in seminars where they reported on unemployment and political oppression of West German workers’ youth and discussed the dangers of false compromises in the policy of détente, and performed a play on the major strikes at the Mannesmann steelworks in Duisburg (in 1976, the play was published as a dramatic cantata).

With the student movement of 1968, the idea of socialism had gained strong momentum among West German youth. This was not the only reason why the West German press polemicised aggressively against the World Festival and the broad composition of the delegation in advance and fabricated the demise of the independence of the youth organisations. From West Berlin, from the roof of the anti-communist Springer publishing house, the participants of the World Festival were even to be treated to a concert by a beat band, which was to present the advantages of western freedom. The socialist section of the delegation, on the other hand, concluded their visit to Berlin with the following statement:

“We leave the GDR on the 28th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The experience of the festival, as well as this date, are an obligation for us not to slacken in our striving for secured peace, worldwide disarmament, and European security.”

Conclusion: Then as now

While the US government invested 13 million US dollars in the overthrow of Allende and, under the auspices of the CIA and high-ranking military officers, prepared the coup in Chile together with the Chilean oligarchy and reactionary military, the representatives of the new and legitimate Chile experienced solidarity with the struggle of the Unidad Popular at the World Festival. While West Germany supplied its NATO partner Portugal with weapons for its bloody war against the liberation movements, those against whom these weapons were directed – fighters from Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique – came together in East Germany. While the USA was killing three million Vietnamese in a devastating war, using almost 400,000 tons of napalm and a highly armed puppet government in South Vietnam, the progressive forces of the other America were reconciling and uniting with the representatives of North and South Vietnam in a common struggle against war and imperialism.

Five years later, when Cuba was hosting the XI. World Festival, Mozambique and Angola had gained independence in the course of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. The victorious people of Vietnam were rebuilding their country. In Chile, however, the Pinochet dictatorship was in its fifth year. Victories and defeats alike bring new challenges, struggles and alliances. Again and again, the progressive youth of the world convene at the World Festival to formulate tasks at hand, to organise together and to express international solidarity for peace and progress – then as now.