KEYWORDS

GDR

History

Economy

Society

Construction

Socialism

Soviet Occupation Zone

East Germany

RISEN FROM THE RUINS

The Economic History of Socialism in the German Democratic Republic

ABSTRACT

CONTENTS

- German Imperialism in the Twentieth Century

- New Antifascist Democratic Beginnings in the Soviet Occupation Zone

- The Establishment of the DDR

- The Starting Point for the East German Economy after 1945

- The DDR’s Economic Achievements

- The DDR’s Internationalism

- ‘Produce More, Distribute Fairly, Live Better!’

- Contradictions in the Practice of a Planned Economy

- The Economic Pillage of the DDR

- Bibliography

Excerpt from ‘Construction Song’ (1948) by communist writer Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956):

Everyone likes a roof over their head

so advice to construction isn’t bad.

For our own good cause we must create,

at very first a brand-new state.

Gone with the rubble, something new be built!

For ourselves only we must care

and come right at us, those who dare.

The German People’s Council was a political committee and SED initiative that was composed of representatives of the various parties and mass organisations in the Soviet Occupation Zone in 1947. It was organised similarly to a parliament and a special committee in the People’s Council drew up the draft of a constitution. The People’s Council convened at the Congress of the People on 7 October 1949 and established itself as the provisional Volkskammer (DDR People’s Parliament); in October 1950, the first vote was held. The Volkskammer would remain the parliament of the DDR and the country’s highest constitutional body until 1990.

- The following resources are considered national public property of which private ownership is prohibited: mineral deposits, mines, power stations, dams, large bodies of water, natural resources found in continental shelves, industrial companies, banks, insurance institutions, state-owned goods, traffic routes, means of transport by rail, sea, and aviation, the post office, and telecommunication installations.

- The socialist planned economy guarantees that public property is used with the aim of achieving the best results for society. The socialist planned economy and socialist commercial law serve this purpose. The use and management of national public property take place fundamentally through state-owned enterprises and state institutions. The state can transfer its use and management by contract to cooperative or social organisations and associations. Such transfers must serve the interests of the general public and increase social wealth.

– Article 12 of the 1968 Constitution of the German Democratic Republic

From the end of the 1960s, individual state-owned enterprises in industry as well as the construction and transport sectors were gradually merged into larger economic units called Kombinate, or ‘combines’. In 1989, around eighty percent of all employees worked in combines. In the combines – a sort of ‘socialist corporation’ – the production, sales, and distribution of a single industry, or even complementary branches of production in different industries, were brought together. The combines had institutes and capacities for research and development and cooperated with academies and universities. The aim of forming a combine was to create more favourable production structures, introduce new types of technological solutions, and improve centralised control. The enterprises belonging to a combine, like the combine as a whole, received their planning tasks from the State Planning Commission.

The Trust Agency was founded in 1990 during the unification process to privatise the DDR’s state-owned enterprises according to the principles of the market economy and to liquidate those that were ‘not competitive’. It took over 8,500 companies with 45,000 locations that employed some four million people and privatised 6,500 companies, selling them far below their value – often for the symbolic price of a single West German DM. Around eighty percent of these companies were sold to West Germans, fifteen percent to foreign investors and five percent to East Germans. Two thirds of all jobs in East Germany were lost, even though West German buyers were subsidised by the state. Violations of the conditions of the liquidation process – such as job retention – went unpunished and many of the labour rights that the West German trade unions fought for were abolished in that process. This was an approach that still, to this day, leaves eastern Germany economically weaker than the West and causes persistent social inequality. As a result, there are now only 850,000 industrial jobs in the territory of the former DDR, four to five times fewer than there were in the DDR. In the agricultural sector, the land taken over by the Trust Agency gained the attention of speculative buyers around the world and local farmers were unable to afford the rising land prices. Agricultural companies from West Germany and other EU countries now own this land.

CONTENTS

- German Imperialism in the Twentieth Century

- New Antifascist Democratic Beginnings in the Soviet Occupation Zone

- The Establishment of the DDR

- The Starting Point for the East German Economy after 1945

- The DDR’s Economic Achievements

- The DDR’s Internationalism

- ‘Produce More, Distribute Fairly, Live Better!’

- Contradictions in the Practice of a Planned Economy

- The Economic Pillage of the DDR

- Bibliography

Risen from the Ruins

With the victory of the anti-Hitler coalition and the defeat of German fascism on 8 May 1945, a new international balance of power was reached. One of the four victorious powers coming out of the Second World War was the Soviet Union, which had been a socialist society since the 1917 October Revolution. The country consistently implemented the joint decisions of the allied powers for the creation of a democratic Germany in its own occupation zone.

In the wake of the dissolution of the anti-Hitler coalition and the beginning of the Cold War between the Eastern and Western Blocs, two German states emerged. In 1949 the Federal Republic of Germany was founded, a bourgeois parliamentary democracy in whose state apparatus and economy perpetrators of the Nazi dictatorship assumed influential positions. In the same year, the founding of the German Democratic Republic as an antifascist-democratic state heralded a complete break with the imperialist past in East Germany. Its alternative concept of social order was inspired by the Soviet Union, but the construction and design of the new state was in the hands of German communists who had learned many lessons from the two world wars.

German Imperialism in the Twentieth Century

During the First World War, the highly industrialised and economically prosperous German Reich had already started to divide up the world and secure markets and raw materials for itself. It had also joined in on the colonial practices of other European powers, exploiting and oppressing people on the continent of Africa as well as in Asia and Oceania, fighting and even committing genocide against the Herero and Nama people in what is today Namibia.

The First World War ended in 1918 with the November Revolution, when workers and soldiers wiped out the monarchy in Germany. This led to the establishment of a parliamentary republic and brought an end to Germany as a colonial power. Though the German emperor was ousted, the generals remained; it was only later, when the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was formed, that the reactionary elite of the politically and economically unstable republic eventually saw that their time had come. The Party’s goals were fully in line with the expansionist interests of German monopoly capitalism, the large-scale landowners, and the military.

In 1933, the National Socialist Party took over the government with Adolf Hitler as its leader. Within a few months, the fascists set up a dictatorship that annihilated internal political opponents by banning political parties and trade unions and imprisoning communists and trade unionists. They took away the rights of the Jewish, Sinti, and Roma people as well as homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and people with disabilities and began to systematically murder them. With an enormous military armament programme, Hitler initiated preparations for a war that would allow German imperialism to achieve world domination, conquer territory in the east for ‘members of the German nation’, and obliterate the ‘Bolshevik subhumans’.

The Second World War began in Europe with the German Wehrmacht’s attack on neighbouring Poland on 1 September 1939, driven by the German Reich and its axis powers Italy and Japan. This war was waged by systematically destroying and liquidating civilian populations – such as twenty million Chinese people in Manchuria and six million Jews in Europe – in the most brutal of ways. Soldiers from the colonies of the allied forces were also among the overall seventy million killed during the Second World War. Great Britain in particular recruited soldiers from its colonies, whose participation in the fight against fascism is largely rendered invisible to this day.

Two years after the beginning of the war, the anti-Hitler coalition was formed by the major powers of the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States to fight as an alliance against fascist aggression. The Soviet Union, however, bore the brunt of the war: two thirds of the fascist divisions were concentrated on the Soviet-German front, and it was here that the most decisive battles were fought. The Wehrmacht and the Schutzstaffel (SS) were relentless in carrying out the order to destroy the conquered territories all throughout Eastern Europe. This scorched earth tactic left behind destruction on an unimaginable scale: in the USSR alone, over 70,000 villages and towns and 32,000 industrial facilities were razed to the ground. More than 26 million Soviet citizens were murdered during this brutal campaign of destruction.

After the Red Army troops fought the Battle of Berlin, the Wehrmacht was forced to surrender unconditionally on 8 May 1945. This marked the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Second World War came to an end on the Western Front. However, this did not necessarily mean that the war was over in other regions. In Asia, for instance, the Second World War had begun as early as 1937 with Japan’s war against China in occupied Manchuria, but it did not end in 1945 with the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the US.

Instead, the end of the war in Europe gave the British, the French, and other colonial powers the ability to focus on crushing independence movements in their colonies. France did this, for example, with bloody massacres in Algeria and with its war against Vietnam, which had been proclaimed independent by Ho Chi Minh in 1945 after the surrender of the Japanese occupying forces. The United States not only continued this war, but also resumed opposition against the partisans fighting in the Philippines who had continued to resist the Japanese occupiers for three years after U.S. forces withdrew in 1942. They were now facing their old colonial rulers once again. However, there were also instances in which colonial powers that had been weakened by war withdrew from their colonies, opening up new possibilities. India, for example, won its independence in 1947, and in China, the civil war ended in 1949 with the victory of Mao Tse-tung’s revolutionary People’s Army over Chiang Kai-shek’s troops.

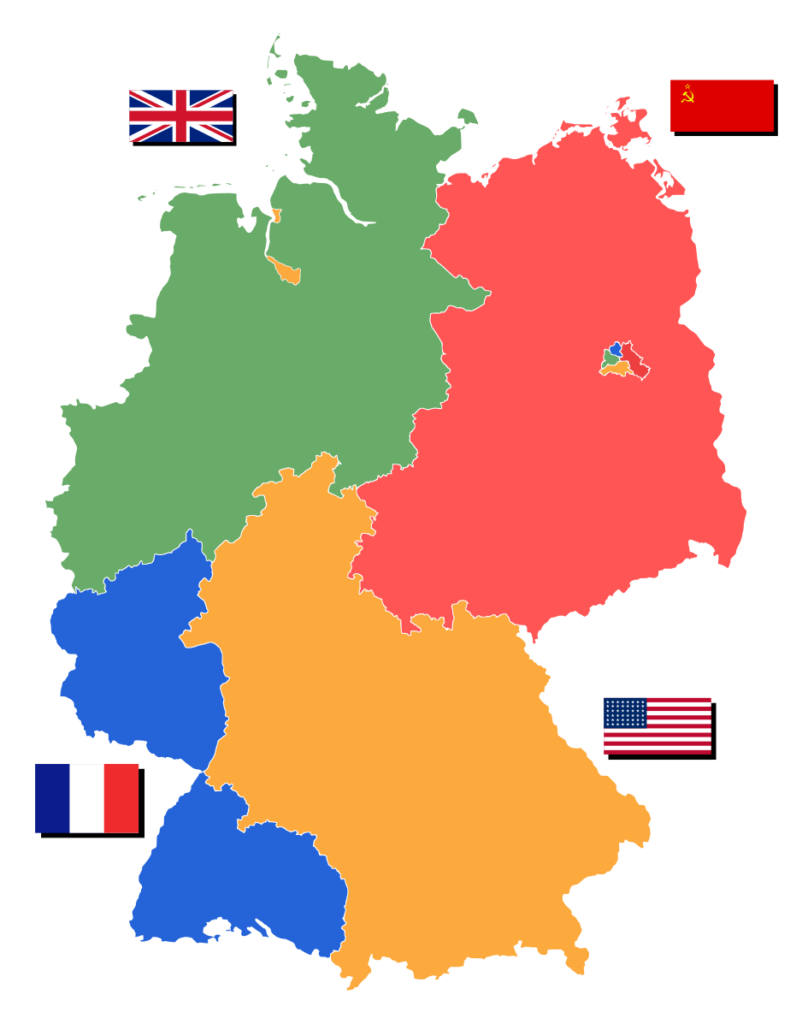

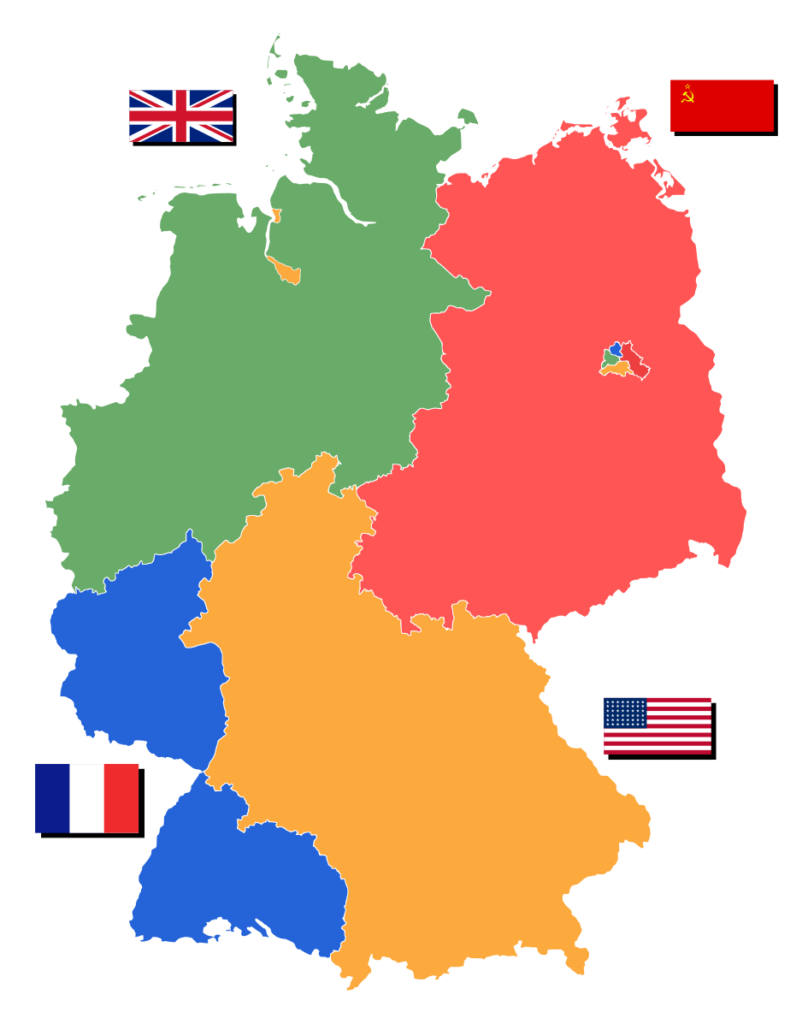

In Germany, the main allied powers of Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States, and France created four occupation zones when the war ended, following the agreements of the anti-Hitler coalition. These zones divided Germany – as well the capital, Berlin, which was located in the Soviet occupation zone – into areas subordinate to the respective victorious powers. The heads of state of the victorious USSR, the United States, and Great Britain met in Potsdam in July 1945 to discuss how to proceed with the defeated Germany and debated the future of the country. Their decisions, backed by France, were aimed at weeding out German fascism by its economic and ideological roots, preserving Germany as a unified whole, and establishing it as a neutral zone. The basic political principles that guided the allies are referred to as the ‘Four Ds’ of the Potsdam Agreement:

- Denazification measures sought to remove all Nazis from relevant positions and punish war criminals.

- Demilitarisation sought to completely disarm and destroy the German arms industry.

- Decentralisation sought to crush the concentration of economic power among monopolistic businesses.

- Democratisation sought to restructure public life.

The Soviet Union knew that it had to ensure that there would never be another war waged against them by the Germans, but preventing future German aggression was also in the interests of the Western allies. Realistically assessing its coalition partners, the Soviet Union was not yet aiming for its occupation zone to be reconstructed according to socialist principles. Its goal was to create a demilitarised, civil-democratic republic that lived in peace with its neighbours and was not involved in any confederation. This was intended to create a non-aligned, neutral state as a buffer zone to Western Europe.

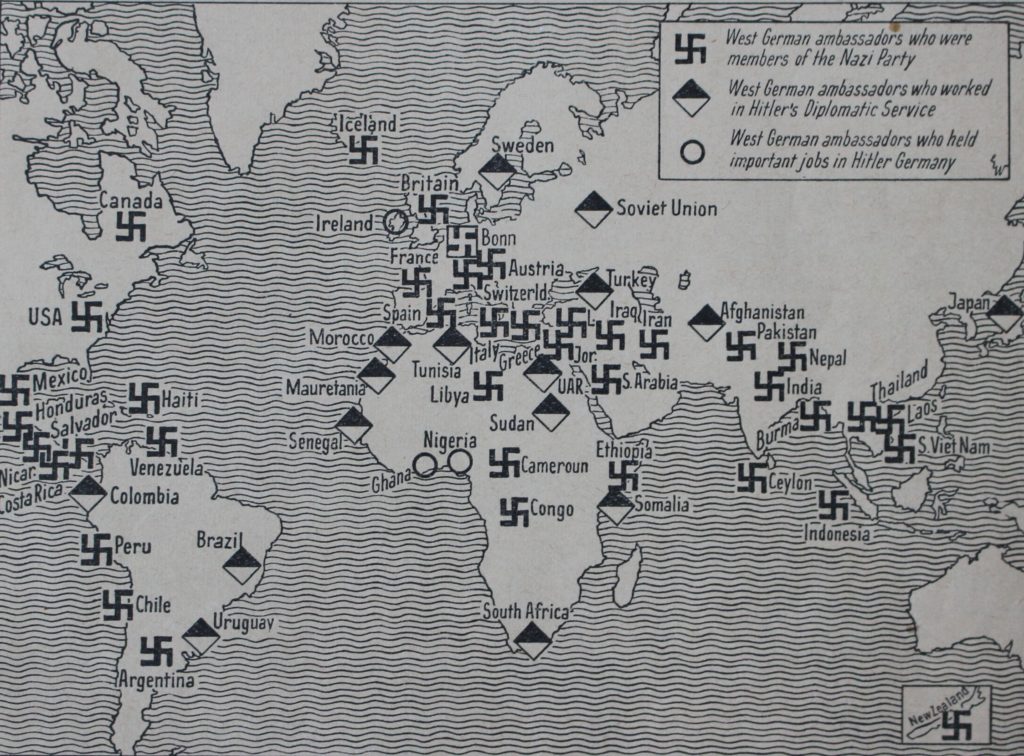

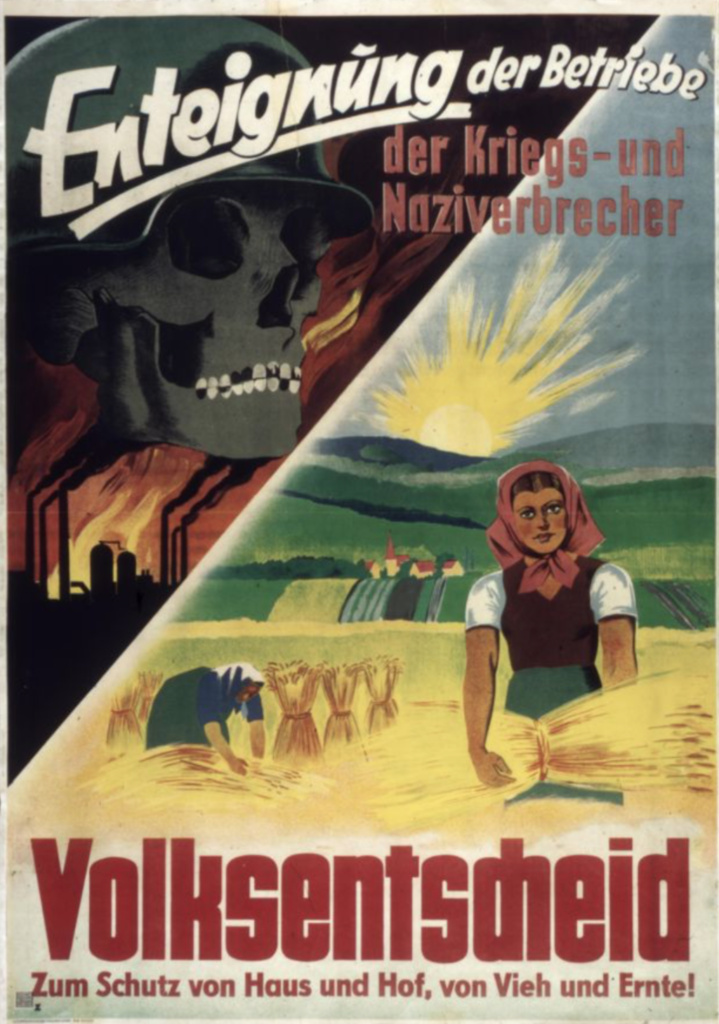

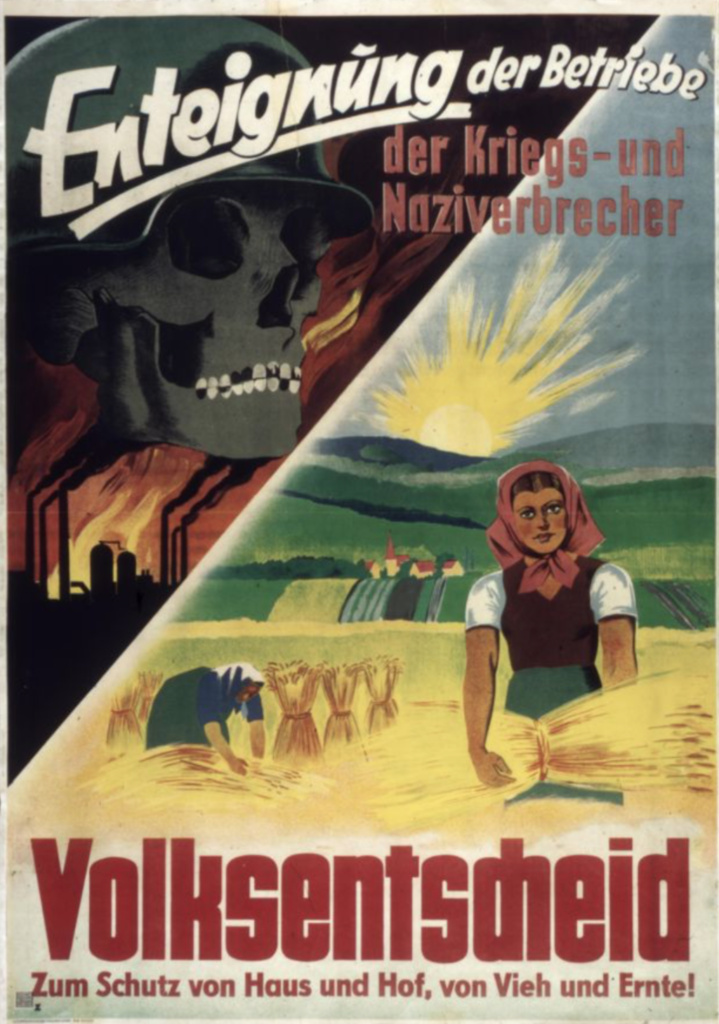

While the Soviet occupation zone began implementing the Four Ds, the Western zones only partially kept the agreement. The joint decisions that had previously been agreed upon became a nuisance, especially when they interfered with issues of private, capitalist ownership. Adherence to the Potsdam Agreement thus became a red line between the different zones. In the East, large companies were transferred to public ownership, and Nazi war criminals were dispossessed of their property, convicted, removed from all institutions, and excluded from assuming important positions in society. In contrast, Western allies forbade expropriation initiatives, and the West depended on the Nazis as seasoned ‘experts’ for which they were economically rewarded in the form of relevant employment. Large businesses that had previously helped the fascists take power were left untouched, as were positions of economic power within German monopolies.

Though all of the occupying powers at the Potsdam Conference had made demands to disempower monopolies and large corporations, these demands were only met in the Soviet Occupation Zone, where around 10,000 businesses were expropriated without compensation. These enterprises became the property of the people and formed a publicly owned production sector alongside the remaining private capitalist enterprises that supplied about a quarter of the country’s total industrial production.

Meanwhile, in the West, the political and military agenda was to safeguard the interests of big business in the three Western occupation zones and to secure the global power of the United States on the European continent. Towards this end, the U.S. military concocted a frightening narrative of communist world domination. A war with the Soviet Union was as good as certain and a test of power was imminent. In March of 1946, British politician Winston Churchill was already redefining the new spheres of influence and began to speak of the ‘iron curtain that [had] descended across the continent’, drawing a line ‘from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic’. The Cold War between the Western powers and the Eastern Bloc had begun.

U.S. President Truman terminated the war coalition with the Soviet Union one year later. The deeply rooted political and economic conflicts that ensued led to the dissolution of the anti-Hitler coalition and subsequently to the establishment of two German states: a capitalist state on the one hand and, on the other, a state that prepared the ground for socialism by expropriating private capital. In 1948, the Western European states of France, Great Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg founded the Brussels Pact, which was then presented as a mutual assistance pact against renewed German aggression. In 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) came into being after ‘requesting’ military assistance from the U.S.; with this development, the U.S. secured its ability to act in Europe against the alleged military threat from the Soviet Union.

In the West, the conservative middle-class political parties pushed for the establishment of an independent state in the interests of the private sector and corporations; such a state could only be capitalist. In 1948, the Western Allies created a ‘trizone’ out of their occupation zones and divided Germany with a currency reform. The introduction of a new currency tied to the U.S. Dollar, the Deutsche Mark (DM), established an economic area based on capitalist principles, from which the Soviet Occupation Zone was excluded. The Trizone became a West German separatist state in May 1949 with the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), also referred to as West Germany.

The West German economy recovered quickly from the aftermath of the war through the massive accrual of capital under the U.S. Marshall Plan (an investment program for the reconstruction of Europe). It was not long before West Germany had grown into the strongest economic market on the continent. With its rearmament and the establishment of an army under the leadership of hundreds of former Nazi military members as well as its entrance into the NATO military alliance, West Germany became a European outpost and protector of U.S. hegemony. From the moment it came into existence, it was one of the most important centres of action in the Cold War against the socialist states.

New Antifascist Democratic Beginnings in the Soviet Occupation Zone

Excerpt from ‘Construction Song’ (1948) by communist writer Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956):

Everyone likes a roof over their head

so advice to construction isn’t bad.

For our own good cause we must create,

at very first a brand-new state.

Gone with the rubble, something new be built!

For ourselves only we must care

and come right at us, those who dare.

After the Second World War ended, the Allied Control Council, made up of the commanders-in-chief of the armed forces of the four winning powers, took over governance in Germany. Orders and directives were carried out at the discretion of the commander-in-chief of each respective occupation zone. Each occupying force also had the right of veto, which allowed them to choose their own path.

The Soviet Union did not export the Soviet system to its zone of occupation when it liberated Germany from fascism; rather, it placed the building of an anti-fascist democratic state in the hands of German communists. As early as June 1945, newly established antifascist democratic parties, unions, and mass organisations began operations with permission from the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD). In 1943, a number of German communists in Soviet exile had founded the anti-Nazi ‘National Committee for a Free Germany’ with German prisoners of war. With the end of the Second World War, several of the committee’s campaign groups returned to Germany to help reorganise public life and build German administrative bodies in accordance with the decrees of the SMAD. Some of the committee’s members took on key roles in the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

In their Appeal to the German People for the Construction of an Anti-Fascist-Democratic Germany from 11 June 1945, the KPD called on the German people to lead the ‘fight against hunger, unemployment, and homelessness’ and to change the previous ownership structures to ‘protect the workers against unbridled entrepreneurialism and excessive exploitation’. By joining all democratic forces, the KPD, together with the other newly formed parties, created an antifascist democratic bloc. In 1946, the two workers’ parties, KPD and SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany), united to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), the leading political party in the Soviet Occupation Zone, and later in the DDR. This resolved a decades-long schism within the working class, which had undermined its ability to fight against the existing ruling order.

In 1945, land reform was launched in the DDR and the feudal Junkers (landed nobility with immense property holdings who had held significant power in the Prussian-German military) had their land expropriated without compensation. Estates of more than 100 hectares, as well as the properties of all Nazis and war criminals, were transferred to a state land trust. More than half a million agricultural workers, resettled individuals, and landless farmers received a piece of property to call their own from this trust.

In autumn 1945, the German Central Administration for National Education was established at the behest of the SMAD. Its task was to create antifascist, secular, and socialist education and school systems. A comprehensive state school system was created that granted the equal right of education to all children for the first time ever. Teachers who had ties to the Nazis were fired from their positions and, in a very short time, around 40,000 young people who had not been tainted by the fascist system were trained to become new teachers.

The Establishment of the DDR

The newly established Federal Republic of Germany declared itself the only successor of the German Reich and the true representative of all Germans. This included the claim to areas east of the Oder and Neisse rivers in today’s Poland, which had been part of the German Reich. After the end of the war, these areas were placed under Polish administration and the new border was then decided in the Potsdam Agreement. However, the border was not recognised by West Germany, which maintained its nationalist claims.

Meanwhile, in East Germany, the administrative functions that were initially carried out by the Soviet military authority were transferred to the newly founded German People’s Council. Shortly after the foundation of the FRG, the German People’s Council met in the Soviet Occupation Zone on 7 October 1949 and founded the German Democratic Republic (DDR). In its first statement, the new republic expressed a commitment to peace, social progress, and friendship with the Soviet Union and all peace-loving states and movements.

The German People’s Council was a political committee and SED initiative that was composed of representatives of the various parties and mass organisations in the Soviet Occupation Zone in 1947. It was organised similarly to a parliament and a special committee in the People’s Council drew up the draft of a constitution. The People’s Council convened at the Congress of the People on 7 October 1949 and established itself as the provisional Volkskammer (DDR People’s Parliament); in October 1950, the first vote was held. The Volkskammer would remain the parliament of the DDR and the country’s highest constitutional body until 1990.

The new state defined itself as a state of workers and farmers and political power was held by the working class and its leading party, the SED. The National Front, a coalition of parties and mass organisations, ensured that all social groups would have influence on and participate in political processes. The DDR’s first constitution enshrined the achievements of the antifascist democratic revolution. It declared that the working class and its allies should exercise state power; that monopolies and large-scale land ownership should be abolished; that a national people’s economy should be created; that all citizens should have the right to employment and education; and that women should have equal rights. Promoting peace and international friendship became the guiding principle of state policy. As expressed in the DDR’s national anthem written by the poet Johannes R. Becher:

Risen from the ruins

And facing the future,

…

The whole world longs for peace,

Extend your hand to the people of the world.

Creating an efficient and powerful economy, however, posed an existential challenge for the new state. An initial five-year plan projected an increase in the labour productivity of state-owned enterprises, a doubling of industrial production, and an increase in the amount of state-owned property. The remaining 17,500 private capitalist enterprises were included in the economic development plan via economic, financial, and tax policies. This first five-year plan helped the DDR switch to long-term socialist economic planning and laid the groundwork for the development of a socialist system, which it finally adopted in 1952.

In 1950, the DDR joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (RGW/COMECON), which had been founded in Moscow the year before. The council was a coalition for economic cooperation established between the Soviet Union and the new people’s democratic states of Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, and it was later joined by other states, including Cuba and Vietnam. Its economic conditions were determined not by capitalist market competition, but by socialist cooperation. The goal of COMECON was to create a shared zone for the people’s democracies and to coordinate their national economic plans. Their economic, scientific, technological, and cultural cooperation was settled in numerous bilateral agreements. In the same year, the DDR recognised the border between Germany and Poland along the Oder and Neisse rivers as a permanently valid ‘peace border’ as stipulated in the Potsdam Agreement. In doing this, the country took an important step towards reconciliation with their former enemies and – unlike West Germany – gave up all claims to the former eastern territories of the Third Reich.

By the mid 1950s, both German states were integrated into the Eastern and Western Blocs respectively. This alliance system influenced each country’s economy, politics, and military. In 1955, the DDR became a member of the Warsaw Treaty, the military alliance of Eastern Bloc states and a mutual assistance pact between socialist states that was exclusively defensive in nature and held peace in Europe as its primary goal. During this arms race forced by the West, the DDR – as a borderland to Western Europe – was a highly sensitive area for the threat of a potential war, sitting at the forefront of the systemic confrontation between communism and capitalism.

‘DDR citizens lived in a country that kept peace and pursued peaceful policies. At the same time, they were citizens of a German state that waged war. … The fall of the Berlin Wall marked the end of the longest peaceful period that Europe had ever experienced. Just a few months later, conflict returned to a continent that had been free of the torments of war since 1945. The border between the two German states was gone, but … the triumph of bourgeois democracy mostly just created new borders. Borders that did not previously exist between the Czechs and the Slovaks or between the peoples of the former Yugoslavia, not to mention the borders that today traverse the former Soviet Union. Many violent conflicts and tens of thousands of deaths resulted from these new boundaries. In 1990, the post-war period ended for the East Germans, and a new pre-war period began.’

A Good Economy – but for Whom?

Economic success is generally measured by revenue and profit. Although these metrics were important for the DDR, they were not at the heart of its economic policy. The country’s production goal was to constantly improve the people’s living and working conditions, not to help the rich and private landowners increase their profits. The fact that the DDR cared about and spent billions on social issues such as housing, holiday leave, childcare, and healthcare is simply unfathomable in today’s neoliberal, profit-oriented paradigm. The economic history of the DDR shows us what it looks like when the needs of the people are given fiscal priority.

The Starting Point for the East German Economy after 1945

At the end of the war, more than a quarter of all homes in East German cities had been destroyed or rendered uninhabitable by allied airstrikes. The use of infrastructure, and thus the supply of raw materials and food, was dramatically limited by the destruction of roads, railways and bridges. In addition, huge assets were taken to West Germany as company owners and senior employees of the former Nazi state fled to the Western zones in order to escape punishment or expropriation.

In violation of the decisions of the Potsdam Conference, the Western occupation zones soon stopped reparations payments to the Soviet Union, which, as the country most damaged by the war, had to withdraw these resources from its own occupation zone. Two thousand and four hundred East German companies were dismantled, including almost the entire motor vehicle industry and more than half of the electrical and iron industries, as well as the heavy machinery and construction industries, and everything was relocated to the USSR. To supply the population in its own country, the Soviet Union also took goods that had been produced in the Soviet Occupation Zone that were supposed to provide for the people of DDR. All in all, seventy percent of pre-war industrial capacity was no longer available, which meant that living standards and productivity in the East were only nearly half of what they were in the West.

In the first eight years after the war, almost a third of all East German production was prevented from contributing to the country’s own economy as a result. Additionally, inequalities in industrial capacity that had been passed down from before the war only became greater with the division of Germany. Machine production for mining as well as steel foundries and mills were located in West Germany. In fact, the entire raw materials industry, including the coal and steel industry, was located there, leaving the Soviet Occupation Zone/DDR completely cut off from all of these resources. This situation put planners in the East German economy at a disadvantage, which they sought to compensate for by increasing productivity.

Without interruption, great efforts and many privations on the part of the population were necessary to build up the economy. The DDR rebuilt its own heavy industry from the ground up, and in record time. As a result, the production of daily necessities such as clothing and food items initially took a back seat. It was not until 1958 that the country could stop rationing its food supply; these were among the hardships caused by the war.

Little by little, West Germany cut off the intra-German trade that was so important for the DDR. Even when individual companies still managed to conduct business with the DDR, West German authorities levied a variety of sanctions against them, and loans were withdrawn or special taxes were charged. However, most disruption tactics focused on sabotaging contracted delivery quotas and interrupting deliveries. These measures threw sand in the gears of intra-German trade, destroying the DDR’s only possibility for obtaining raw materials and durable equipment that their partners in Eastern Europe could not produce because of their own economic hardship. Moreover, West German companies traditionally manufactured products that were custom tailored to the needs of East Germany; only these companies were able to produce to the same standard of goods and offer duty-free deliveries of goods from nearby. There was no duty to pay because West Germany did not recognise the DDR as a state and therefore not as a foreign country either. In this way, West Germany’s exclusive mandate policy functioned as a lever of economic extortion.

With only seventeen million inhabitants, the DDR was a small country that could only compete in science and technology by partnering with experts internationally. However, the Cold War and embargo policy prevented them from participating in specialised and cooperative projects around the world. This is precisely what happened when the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), led by the United States starting in 1949, blocked the export of Western technology into the Eastern Bloc. This prevented the East from having a part in technological advances and from hiring international labour in the fields of science, research, and development. The DDR would require immense resources as well as both scientific and technological development in order to fill in the gaps that these embargo measures left in the country’s economy.

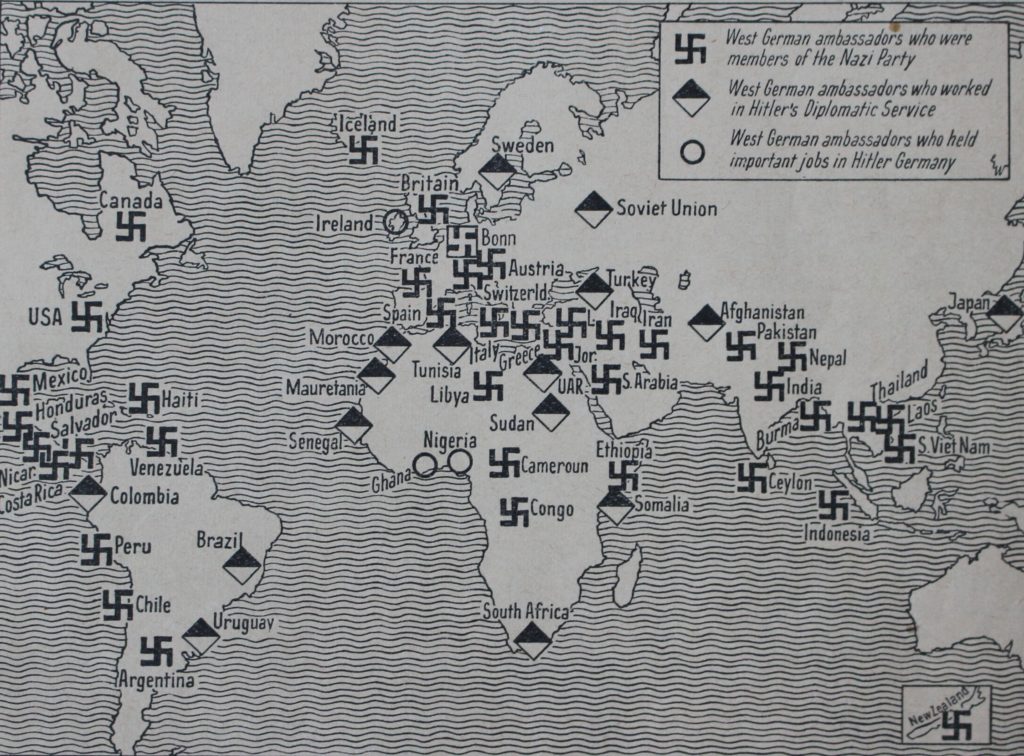

West Germany developed guidelines in the mid-1950s through the Hallstein Doctrine to economically isolate and further weaken the DDR. Every official recognition and establishment of diplomatic relations with the DDR was to be understood as an ‘unfriendly act’. Any state that questioned West Germany’s exclusive right to the sovereign representation of Germany was threatened with a variety of economic and political sanctions and the breaking of diplomatic ties. The Hallstein Doctrine became a huge impediment to trade: DDR passports were not recognised; diplomatic relations, embassies, and trade and payment agreements were forbidden; and a restrictive licensing policy was imposed.

West Germany’s unchecked access to raw materials and assets from the war, combined with its refusal to make reparations payments, gave the country a fundamentally different economic starting point after the war. This structural advantage could be seen through the West’s decisive industrial locations, considerably lower reparation payments, and unhindered access to raw materials. In addition, the United States pumped capital into the Federal Republic, providing for a quick resuscitation of the economy and better conditions for the West German people. This inequality also led many people to emigrate from the East to the West. Fifty percent of those who left were young and highly qualified. In the 1950s alone, a third of all academics left the DDR. This was an enormous loss, as their education had been financed by the state they were leaving and they were urgently needed to rebuild the country. With the construction of the Wall in 1961, the DDR leadership sealed off the route via West Berlin into West Germany and stopped further emigration.

The DDR’s Economic Achievements

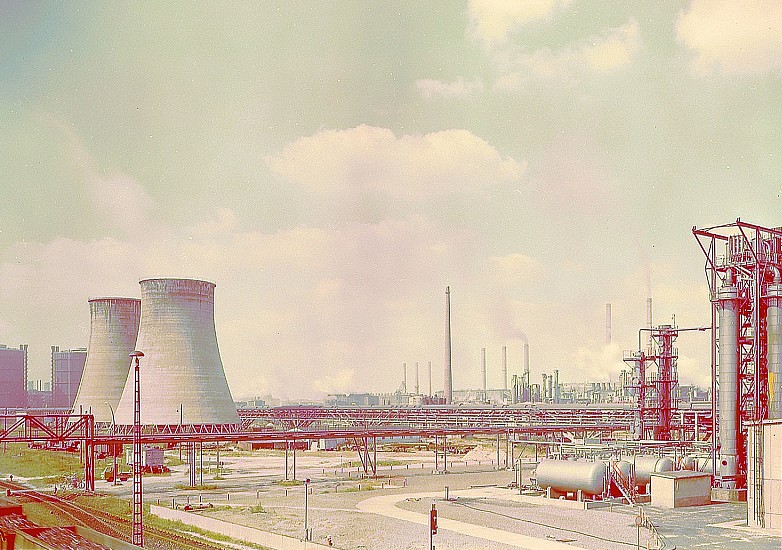

In the 1950s, the large gaps in the production chain caused by the war and reparations continued to loom over the DDR’s economy. The economic isolation of the DDR led to pragmatic choices: if there was no iron coming from the West, then it had to be mined locally, no matter how poor the quality or how expensive it was to produce. If no coal or oil was available, then they used the only thing left: brown coal. Brown coal, or lignite, was the only raw fuel that was available in the East in significant quantities. Though using it was not environmentally friendly, there was no alternative due to external circumstances. The creation of the DDR’s own iron, steel, and machine industries as a basis for its industrial development was the main focus of development in the DDR’s early years. The first Five-Year Plan therefore envisaged doubling industrial production between 1951 and 1955.

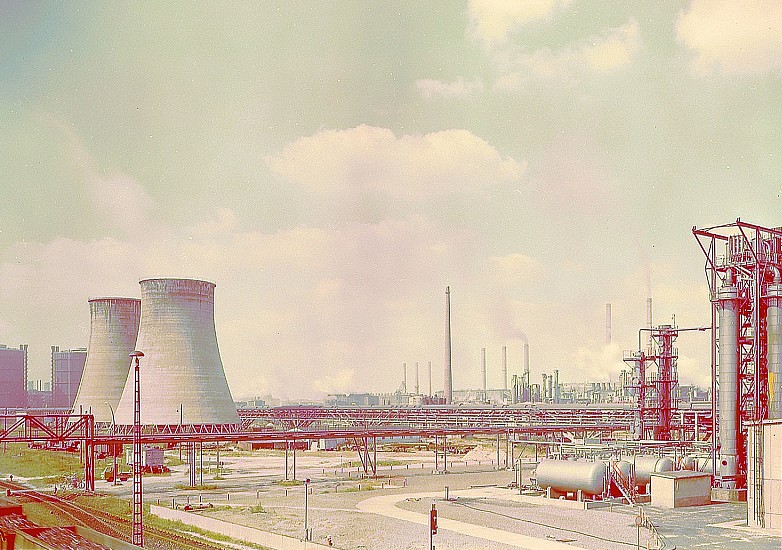

The enormous factories that were built all over the republic as a result brought young people into previously sparsely settled regions. New villages and towns were built and became home to thousands of people. In forty years, the DDR fundamentally changed the face of the formerly underdeveloped agricultural region of East Germany. With the gradual stabilisation of the East German economy and the growth of production, the country was able to attract an ever-increasing volume of investment. In the years between 1950 and 1960 alone, this volume increased more than three-fold.

The DDR also had the ambitious goal of overcoming the economic and social differences between the northern and southern regions and eradicating the inconsistencies between urban and rural industrialisation. The degree of industrialisation in the south was significantly higher than in the north. In order to reconcile the disparity between urban and rural areas, the DDR developed a new agricultural system, which was characterised by land reform and the collectivisation of the means of agricultural production. The country soon began to develop and expand its energy-producing regions in traditionally agricultural areas and built large-scale industrial plants which at the time were among the most modern in Europe. It also built new power plants, including the largest lignite refining plant in Europe in 1955.

Modern production centres increasingly changed the face of regions that previously had barely been able to feed their impoverished populations. On the Baltic coast, for example, the development of the maritime and port industries accelerated and the fishing and shipbuilding industries became the driving force in the region. Large fish processing plants and suppliers for ship construction and maintenance were set up while imported goods underwent industrial processing. As port facilities steadily grew, these advances boosted trade in the region and the northern regions were able to catch up with the rest of the country.

Even though the DDR started out with unfavourable conditions and many structural disadvantages, the country achieved an average economic growth of 4.5 percent in its forty years of existence. Despite this, it still generally lagged behind West Germany. Back then, as today, the failure of the planned economy was cited by the West as the reason for this shortcoming. This perpetuates the myth that there is no alternative to the market economy. The available figures, however, force us to question this narrative; at no point in the forty years of the DDR’s existence did economic growth stagnate or decline, despite uneven starting conditions.

The country also had a considerable capacity for research and development. For every 1,000 industrial workers, twenty-three were employed in these fields, putting the DDR on par with other Western industrialised countries. Although more funds were available for research in the West, DDR research still registered 12,000 patents in 1988 – the seventh largest amount worldwide. As a result, the DDR was able to increase its industrial production by a factor of 12.3 by 1989 and quintuple its gross domestic product to 207.9 billion euros in today’s terms, making it one of the fifteen leading industrialised countries in the world at the time.

Half of the DDR’s national income was generated by foreign trade. In 1988, the DDR exported and imported two-thirds of its goods to and from the socialist economic zone and to a total of over seventy states, with West Germany as its largest western trading partner. Such a high volume of exports was a sign of considerable integration into the world of international trade, making the DDR the sixteenth largest producer of exports globally and tenth largest in Europe. Through determined economic planning, it proved possible to keep imports and exports in balance throughout the forty years of the country’s existence.

The East German Mark (Mark der DDR) was a domestic currency that was not convertible in foreign trade or international travel. In order to get freely convertible currency, which the country urgently needed for purchases on the world markets, the DDR often sold its goods at excessively low prices below their actual value. This led to an arrangement in which West Germany would supply the DDR with large quantities of chemical and other raw materials (coal, coking coal, crude oil) and then buy refined products (motor gasoline, heating oil, plastics) cheaply. Incidentally, the environmental impact of these refining processes was absorbed by the DDR.

In order to improve the foreign exchange situation, numerous state-owned companies in the DDR were commissioned from the 1970s onward to manufacture products for Western companies under the Permitted Production scheme, in part by using raw materials supplied by the West. This allowed Western companies to profit from the low wages in the DDR, though it is futile to compare wages in the East and West without taking into account factors such as the ‘second pay check’ provided to DDR citizens in the form of subsidised prices for rent and basic foodstuffs as well as free social services.

The DDR used the money from its exported products to pay for both the import of crucial raw materials as well as for the construction of modern facilities needed to build up its economy. It constructed these facilities with the help of capitalist trading partners, though these foreign partners did not receive a financial share in the constructed facilities, as is customary with capital exports. This prevented foreign capital from gaining a foothold in the DDR.

The DDR’s Internationalism

Even as the DDR’s reputation as a reliable and fair economic partner grew worldwide, it was still denied international legal recognition outside of the socialist bloc countries up until the early 1970s. The DDR’s support for liberation movements against colonial powers – i.e. for national movements against post-colonial dependence and imperialistic intervention in former colonies – ensured growing sympathy in developing countries where the DDR made a name for itself as a champion in the fight against neo-colonialism and imperialism. Western foreign policy was comparatively anachronistic: colonies were held onto with an iron grip; apartheid regimes were maintained; the fascist remains of Salazar’s Portugal and Franco’s Spain were supported into the 1970s; there were constant attempts to install dictatorships and puppet regimes in former colonies and dependent territories; and constructs such as ‘South Vietnam’ were enforced through mass murder. Western States secured their temporary and bloody victories in ways that had very little to do with democracy, freedom, and human rights – even according to their own standards.

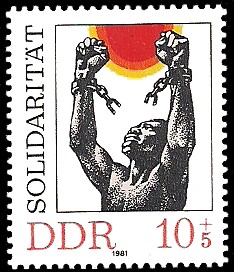

In contrast, the DDR supported a number of liberation movements. Among them were the Vietnamese People’s Army during the Vietnam War; the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) in Nicaragua; the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO); the Zimbabwe African People’s Union; the African Independence Party of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC); and the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). While the West was slandering Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) as terrorists and ‘racists’ and conducting business with the apartheid regime in South Africa – even providing arms shipments – the DDR supported the ANC, provided the freedom fighters with military training, printed their publications, and cared for its wounded. After black students in the township of Soweto launched an uprising against the apartheid regime on 16 June 1976, the DDR began to commemorate international Soweto Day as a sign of solidarity with South Africa and their struggle. In the former German colony of Namibia, the DDR supported the fight for independence and took in several hundred children so that they could grow up in safety and receive an education. When the DDR eventually dissolved, these young people were deported back to Namibia by unified Germany, leaving them to fend for themselves.

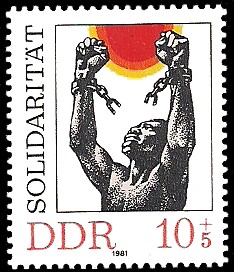

The DDR’s international positioning and commitment to solidarity was not just a matter of foreign policy or the work of civil society groups – it was a widespread mass phenomenon throughout society that was deeply embedded in everyday life. Friendship among nations was reflected in huge, artistically designed murals as well as in letters and stamps. Donations from citizens were collected centrally through the DDR’s Solidarity Committee, which received a total of 3.7 billion East German Marks between 1961 and 1989. Fundraising was organised primarily through the mass organisations, such as the Free German Trade Union Federation of the DDR, in which workers contributed through a variety of solidarity actions. Purchasing solidarity stamps and working above the target and donating the extra wages to the solidarity fund are two among many such examples.

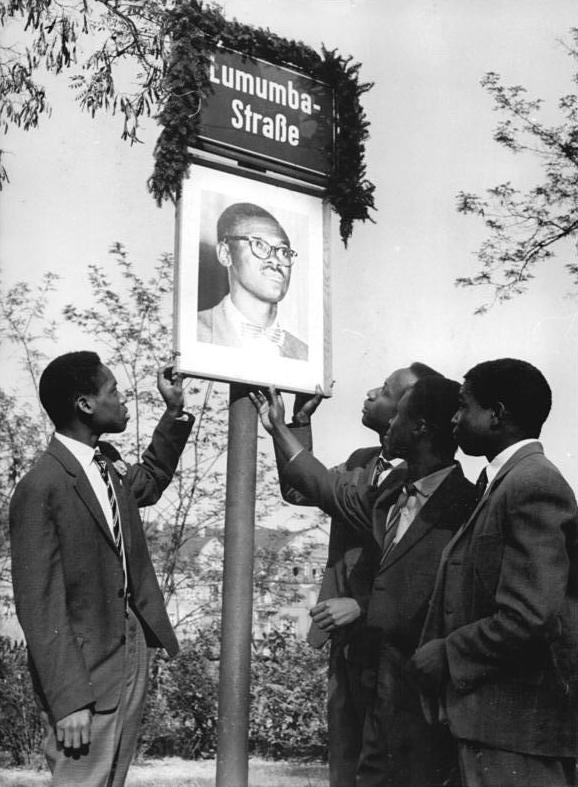

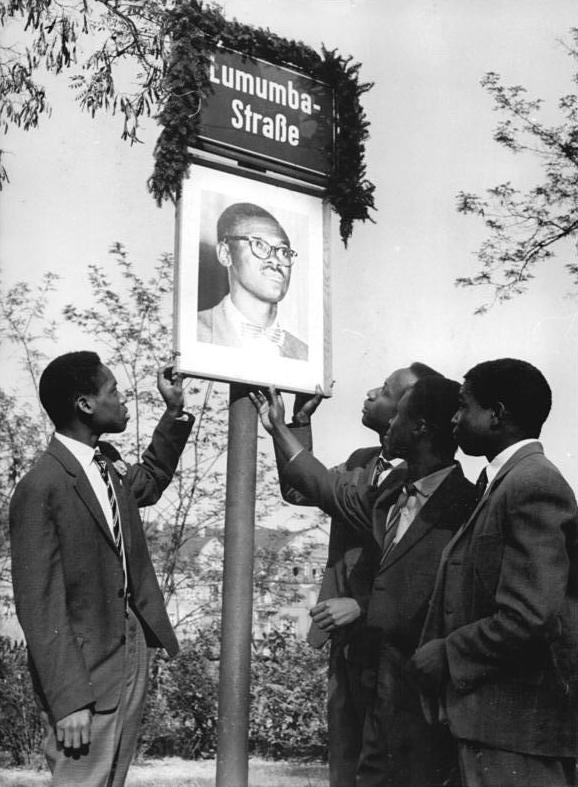

The heroes of independence movements in the Global South were well-known to DDR citizens, even as the West continued to portray them as criminals and uneducated beggars who would have no future without the help and guidance of the West. The names and fates of people like Patrice Lumumba, Kwame Nkrumah, Ahmed Sékou Touré, Julius Nyerere, Agostinho Neto, Samora Machel, and Nelson Mandela were known and celebrated in the DDR. Solidarity was even extended to those in the belly of the beast; when Angela Davis was tried as a terrorist in the United States, a DDR correspondent presented her with flowers for Women’s Day. In a much greater display of solidarity, students in the DDR led the One Million Roses for Angela Davis campaign, during which they delivered truckloads of cards with hand-painted roses to her in prison. The judge was impressed and every child in East Germany knew who Angela Davis was.

Though their stories are not as well-known, there was nonetheless a huge number of DDR citizens – young people, students, scientists, and workers – who took part in solidarity projects all over the world. Between 1964 and 1988, sixty friendship brigades of the Free German Youth (the DDR youth mass organisation) were deployed to twenty-seven countries in order to share their knowledge, help with construction, and create training opportunities and conditions for economic self-sufficiency. A number of these projects still exist today, though some have taken on different names, such as the Carlos Marx Hospital in Managua (Nicaragua), the German-Vietnamese Friendship Hospital (Hanoi, Vietnam), and the Karl Marx Cement Factory (Cienfuegos, Cuba), to name but a few.

At the same time, many young people from all over the world came to the DDR to study. The first foreign students were eleven young Nigerians who had attended the World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin in 1951. When the British colonial government refused them re-entry to their home country, they were offered admission to the University of Leipzig. The preparatory class in which they were taught the German language developed into the Herder Institute, where foreign students took a one-year language course to prepare for their studies. More than 22,000 students from 134 countries graduated from the institute, which also sent lecturers to foreign universities.

The special attention given to African states and anti-colonial movements was reflected in the increasing number of students. Overall, more than 50,000 foreign students successfully completed their education at the universities and colleges of the DDR. The studies were financed by the DDR’s state budget. As a rule, there were no tuition fees, a large number of foreign students received scholarships, and accommodation was provided for them in student halls of residence. The DDR also welcomed children, such as those from Namibia who were brought to safety from the dangers of the war of independence. The School of Friendship (Schule der Freundschaft) was also planned in the late 1970s to provide schooling and vocational training in the DDR for 899 children and young people from Mozambique beginning in the 1980s.

In addition to the students, many unskilled workers – so called contract workers – came to the DDR from allied states seeking job training and work in production. The Agreement on Education and Employment for Foreign Workers brought workers primarily from Mozambique, Vietnam, and Angola as well as from Poland and Hungary. After the dissolution of the DDR, these contracts were terminated, which meant that most of these workers lost their residence permit and did not receive pending wages or compensation. Though West Germany had previously backed temporary work migration, at the end of the 1980s Western European headlines declared that ‘the boat was full’ as right-wing parties enjoyed increasing success and – once the DDR was absorbed – West Germany prepared to abolish the right to asylum.

Up until the very end, the DDR worked towards deepening its commitment to internationalism. The number of foreign contract workers grew from 24,000 in 1981 to 94,000 in 1989. In the same year, China indicated that it wanted to greatly increase its number of contract workers in the future. This would have been very opportune for the DDR, which – unlike in the West at that time – did not have a big enough labour force. China, along with the other socialist states, likewise stressed that it could only stand to benefit from a growing East German economy. This same year, all foreigners in the DDR received full municipal voting rights and began to nominate candidates themselves. This form of participation is denied to non-citizens in present-day Germany.

Yet another vivid example of international cooperation between socialist states was the relationship between the DDR and Vietnam. In order to guarantee the supply of coffee, whose rising world market prices strained the DDR’s limited foreign exchange reserves, the DDR invested heavily in coffee cultivation in Vietnam by supplying material, exchanging with experts, and developing technical and social structures, some of which still exist to this day. This cooperation created the foundation for Vietnam to be the second-largest coffee producer in the world today.

Unlike today’s trade relations between capitalist states, the DDR did not simply buy into a country; it cooperated with its trading partners. The maxim applied here was that the DDR did not set blanket guidelines; rather, it determined what cooperation with its partner countries would look like depending on their respective economic needs. This was an international economic system that aimed at cooperation and the promotion of sovereignty rather than competition and dependence.

This kind of solidarity work provided a stark contrast with the West’s development aid, through which richer nations leveraged their resources to maintain their position of power and enforce the sales of their own industries at the expense of the development of others. Since the West’s supposedly selfless acts are motivated by a hunger for profits rather than a commitment to solidarity, this alleged altruism tends to be imperialist in that it places conditions for aid under capitalist auspices, from which corporations stand to benefit. In contrast, the DDR, together with its socialist allies, acted as equals and as needed. In the countries where it provided aid, it supported the establishment of economic self-reliance by helping to build local industries and infrastructure according to the needs of the respective country, such as by training people.

This attitude and these actions of the DDR received international political recognition. The first country outside the Eastern Bloc to give diplomatic recognition to the DDR was the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar (later Tanzania) in 1964. The DDR subsequently sent ships full of construction materials as well as engineers and construction workers to the republic. These workers set up two large, prefabricated housing districts on the archipelago of Zanzibar that to this day provide highly sought-after housing for around 20,000 people. This triggered a breakthrough in international recognition throughout the Global South. In 1969, Sudan, Iraq, and Egypt established diplomatic relations with the DDR, and in 1979, the Central African Republic, Somalia, Algeria, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Guinea followed suit.

Under the pressure of this wave of recognition, West Germany’s new coalition government of Social Democrats and the Liberal Party abandoned the Hallstein Doctrine in 1969 and tolerated the legal recognition of the DDR. However, it still maintained to the bitter end that every DDR citizen was foremost a citizen of their country. Between 1972 and 1974, when Western states began initiating diplomatic relations with what it referred to as the ‘second German state’, the DDR had already achieved what it had been fighting for throughout the last twenty years: international recognition.

In June of 1973, both West Germany and the DDR were accepted into the United Nations, where the DDR consistently campaigned against nuclear weapons, advocated for international security and disarmament, and played a decisive role in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, among other initiatives.

‘Produce More, Distribute Fairly, Live Better!’

The DDR’s socialist plan was based on the Marxist view that a socially just society could only be created by using socialised means of production. Socialist ownership had three possible forms: public property owned by the whole society (People’s Property), cooperative joint ownership by worker collectives, and property owned by social organisations. The constitution stipulated that the operation of private business enterprises, which continued to exist to a lesser extent, must ‘satisfy social needs and serve to increase the welfare of the people’. Furthermore, ‘private business partnerships to establish economic power’ were not permitted. These constitutional principles were rigorously enforced and, by 1989, public ownership in industry and skilled trades had risen to 98 percent.

- The following resources are considered national public property of which private ownership is prohibited: mineral deposits, mines, power stations, dams, large bodies of water, natural resources found in continental shelves, industrial companies, banks, insurance institutions, state-owned goods, traffic routes, means of transport by rail, sea, and aviation, the post office, and telecommunication installations.

- The socialist planned economy guarantees that public property is used with the aim of achieving the best results for society. The socialist planned economy and socialist commercial law serve this purpose. The use and management of national public property take place fundamentally through state-owned enterprises and state institutions. The state can transfer its use and management by contract to cooperative or social organisations and associations. Such transfers must serve the interests of the general public and increase social wealth.

– Article 12 of the 1968 Constitution of the German Democratic Republic

The DDR’s approach to economic management was also closely tied to the issue of ownership. In the socialist planned economy, economic and social processes were centrally governed by the state and the leading party. Businesses were given concrete scheduled tasks regarding the amount, structure, and distribution of their products and were also allocated the funds needed for investment, the labour force, and materials. National economic goals were mostly scheduled in prospective plans over a period of five years, and the necessary development of economic capacity was planned as well. In keeping with the principle of democratic centralism, the authorities’ economic plans were first given to the combine enterprises (Kombinate) and farms and then decisions were taken based on their feedback.

From the end of the 1960s, individual state-owned enterprises in industry as well as the construction and transport sectors were gradually merged into larger economic units called Kombinate, or ‘combines’. In 1989, around eighty percent of all employees worked in combines. In the combines – a sort of ‘socialist corporation’ – the production, sales, and distribution of a single industry, or even complementary branches of production in different industries, were brought together. The combines had institutes and capacities for research and development and cooperated with academies and universities. The aim of forming a combine was to create more favourable production structures, introduce new types of technological solutions, and improve centralised control. The enterprises belonging to a combine, like the combine as a whole, received their planning tasks from the State Planning Commission.

The planning authorities determined the prices of all goods and services so that uniform prices were set for all consumer goods throughout the DDR. Likewise, the training of skilled workers and university cadres was also centrally planned and carried out in accordance with economic requirements and designated deployment areas. The DDR was based on the principle that permanent full employment was both the best social policy and a human right. An indispensable part of socialist society in the DDR was therefore the right and duty to work, a value that was enshrined in the constitution: ‘Every citizen of the German Democratic Republic has the right to work. They have the right to a job and the right to choose it freely according to the needs of society and their personal qualifications’.

The declared objective, which was further specified in numerous legal provisions and economic policy concepts, was to organise work in such a way that everyone participated in the work according to their abilities and received their individual share of the national product according to their performance. This socialist performance principle ensured that individuals’ contributions to society determined the degree of social recognition they received for their work. In this way, the DDR saw itself as a meritocracy which applied the principle ‘from each according to their abilities, to each according to their contribution’ – an adaption of Karl Marx’ ‘from each according to ability; to each according to need’ first outlined in his 1874 Critique of the Gotha Programme. An important instrument of labour was the Socialist Competition, the first of which was launched in 1947 in a number of state-owned enterprises in the Soviet Occupation Zone under the slogan ‘Produce more, distribute fairly, live better!’. In it, members of a workers’ collective committed themselves to increasing productivity in order to fulfil the plan particularly quickly or above target.

The rights and duties of working people – such as joint decision making in businesses, involvement in shaping working conditions, and respect for the dignity of the working class – were laid down in a Labour Code, likely the only one of its kind in the world.

Collective company agreements were signed annually between management and labour collectives, which served both to meet the specifications of the plan and to improve the working and living conditions of the workers. Ninety-eight percent of workers were members of the Free German Trade Union Federation. Concrete arrangements were agreed upon between the company trade union leadership and company management in order to ensure the health and social welfare of workers; to shape working conditions; to develop intellectual, cultural, and sporting activities; to promote training; and to continue education. Particular attention was also paid to shaping working conditions; developing intellectual, cultural, and sporting activities; promoting training; and continuing education, particularly for women. After discussing the plans at company union meetings, they were implemented and then reviewed at general meetings twice a year by the union’s accountability team and company management. These collective company agreements guaranteed that workers were involved in the management and planning of the company.

Citizens of the DDR lived with a high level of social security. Everyone was guaranteed a source of work and a place to live. The state provided billions of marks in subsidies for rent and basic foodstuffs, while low rents and stable prices for consumer goods, electricity, water, and transit ensured a comfortable daily life. In the beginning of the 1970s, a housing construction programme was launched in a major effort to solve the social problem of insufficient housing. While up till then the maxim had been ‘To each an apartment’, the goal now became ‘To each their own apartment’. However, the focus on building complex new housing units, as well as the creation of social infrastructure with schools, kindergartens, sports facilities, polyclinics, stores, restaurants, and cinemas, minimised the capacities for the necessary renovation of old inner-city neighbourhoods. Even so, over a million homes were rebuilt and two million new homes were constructed. In the DDR’s final twenty years, half of its citizens were able to relocate to a new home.

Education and healthcare were free, and a wide range of educational, cultural, and leisure activities were accessible to everyone. The DDR also led the world in terms of women in the workforce: in 1989, ninety-two percent of all women were employed and almost fifty percent of all university students were women. It was possible for working mothers to have a career and a family through special socio-political measures such as the maternity year, household day (a paid holiday for tending to housekeeping chores), special study programmes for women, state assistance for new mothers, comprehensive childcare, and education services for children. The DDR was also a child-friendly state. Kindergarten, day-care centres, school meals, summer camps, and sports activities were affordable for everyone or provided free of charge.

These social benefits took up a large part of the country’s economic, labour, and investment capacity, but this also meant that society was no longer divided according to how much property one owned and the gap between rich and poor was minimised. The DDR was an equal society, a community based on solidarity. In the words of the East German writer Daniela Dahn, it was a society in which ‘togetherness mattered more than possessions’. There was no neighbourhood for the rich. Instead, everyone existed on the same playing field. There were no elite schools, just free education for everyone and support for gifted children. There was a rich cultural life accessible to everyone. Nobody was left behind. Homelessness and unemployment were virtually non-existent. It is precisely these aspects of socialism in the DDR that will be further examined in subsequent issues in this series, Studies on the DDR.

Socialist Ideals, Sobering Conditions, Open Questions

‘The worst socialism is better than the best capitalism’, wrote Peter Hacks, a poet who migrated from West Germany to the DDR. ‘Socialism, that society that was toppled because it was virtuous (a fault on the world market). That society whose economy respects values other than the accumulation of capital: the rights of its citizens to life, happiness, and health; art and science; utility and the reduction of waste.’ For when socialism is involved, it is not economic growth, but ‘the growth of its people that is the actual goal of the economy’.

Contradictions in the Practice of a Planned Economy

‘If you want to set up a new and better social system, you should learn this lesson: It only works if the majority of the people benefit from it. We learned that good working and social conditions are quickly taken for granted. People succumb to the seduction of ownership and consumption if they think that another system can offer them something better. … The DDR’s social system had as its declared goal the ever-growing material and cultural satisfaction of its people. This goal was supposed to be achieved through sharply rising productivity. If it could have surpassed capitalism in production, then socialism would have been the victor. … The people were encouraged to accomplish this task in the 90s. But it was an unrealistic and misguided goal. Unrealistic because a leading capitalist country that exploits people and nature, such as West Germany, cannot be surpassed in productivity and efficiency. Misguided because, in a socialist society, mass consumption should not be life’s main purpose. This insight eluded socialist leadership in Europe, and therefore they could not impart it to their people. The people recognised that this was a false promise and were no longer willing to tolerate the illusion. They wanted to be taken seriously and took to the streets under the slogan “We are the people”’.

The unlimited world of the goods of the West and its pop culture produced ever new needs, especially among the youth of the DDR, which were considered ‘unsocialist’ because of their association with capitalism. Economic plans could not keep pace with the aspirations of many citizens for Western consumption levels, which led to frustrations. These were intensified when, starting in 1974, DDR citizens who had convertible currency – for example, as gifts from relatives in West Germany or even through income from their own international activities – were able to buy Western imported goods in special stores called Intershops. On the part of the political leadership, the expectation that social policy achievements of the state would directly increase the working people’s willingness to perform, and thus increase labour productivity, was not borne out. Expenditure on subsidies ate away at economic output without stimulating production to the same extent while competition with its Western neighbours repeatedly prompted the DDR to take social measures which it could not afford.

‘Competition between social systems was no longer about life goals – it became about consumption standards. But if the battle with a world of superior cultural offerings was to be won at all – and one can ask whether this was ever really possible – then at least it would not have been based on their own consumer goods production, but on an alternative value system that focuses on the development of humankind as a whole and its culture’.

With the aim of giving more daily visibility to the connection between individuals’ work performance and their respective economic and social standing, a process of economic modernisation began in the 1960s. A new economic system of management and planning was designed, which, through profits and bonuses, made companies more performance-oriented and at the same time more responsible. This concept, however, did not find resonance in any of the DDR’s fellow socialist countries. There was still a lack of coordination in scientific and technological development among the COMECON members.

The principle of ‘unity between economic and social policy’ formulated in the beginning of the 1970s took for granted that enough would be produced and that it would be produced efficiently. However, worsening foreign economic circumstances strained the national economy, particularly in regards to rising energy costs. Between 1970 and 1990, the price of oil rose thirteen-fold and the cost of mining brown coal doubled.

Despite this, the government stuck to its promises to provide social benefits and did not question the exceptionally high subsidies it paid for consumer prices and rents. The result was that urgently needed modernisations never happened, such as in the raw material and chemical industries. A national economic and social policy for the benefit of the population can only exist if there is a high proportion of socially owned property. In the DDR, this proportion was so high that it hindered initiatives in skilled trades, small businesses, and retail trades. One of the problems with the economy was that plans and balance sheets were always tight and often exaggerated, leaving very little margin of error for unexpected developments.

DDR citizens looked at the ‘rich’ West and began to compare it to their own standards of living. But many were loath to evaluate the purchasing power of their money according to the cost of the goods needed for daily life. In the DDR, a 5,000-Mark price tag on a new colour TV may have been a source of frustration, but the fact that two kg of bread cost only one Mark was taken for granted. Basic foodstuffs and goods for daily use were subsidised, while the prices for non-essential products were intended to cover costs and generate a profit. This connection was not obvious to large sectors of the DDR’s population. Furthermore, there was no official exchange rate between the East German Mark and the West German Mark. The DDR Mark was an exclusively domestic currency, but a comparison of relative prices of the same everyday goods in the East and West concluded that the purchasing power of the Mark in the DDR in 1990 was actually eight percent higher than the purchasing power of the Deutsche Mark (DM) in West Germany.

The Economic Pillage of the DDR

The first socialist German state was exposed to prejudice and attempts at delegitimisation both during and after its existence. Today, Germany’s politics of remembrance paint a picture of a ‘totalitarian dictatorship’ with its ‘feeble economy’. The country’s remarkable economic performance and social indicators are denied and the widespread narrative of the takeover of a bankrupt state persists.

However, the DDR was not as ‘run-down’ as is claimed. There were some old and inefficient factories, but there were also highly productive ones. Half of all industrial equipment was less than ten years old and more than a quarter was not even five years old – remarkable figures when compared with those of other countries. There were many modern enterprises with machinery that had been partly imported from the West and partly produced by the DDR’s mechanical engineering industry or by special combine enterprises. These enterprises could have remained in operation, but when the DDR dissolved, the Trust Agency, which was put in charge of the DDR’s economy, rapidly privatised the DDR’s enterprises and eliminated East German competitors.

The Trust Agency was founded in 1990 during the unification process to privatise the DDR’s state-owned enterprises according to the principles of the market economy and to liquidate those that were ‘not competitive’. It took over 8,500 companies with 45,000 locations that employed some four million people and privatised 6,500 companies, selling them far below their value – often for the symbolic price of a single West German DM. Around eighty percent of these companies were sold to West Germans, fifteen percent to foreign investors and five percent to East Germans. Two thirds of all jobs in East Germany were lost, even though West German buyers were subsidised by the state. Violations of the conditions of the liquidation process – such as job retention – went unpunished and many of the labour rights that the West German trade unions fought for were abolished in that process. This was an approach that still, to this day, leaves eastern Germany economically weaker than the West and causes persistent social inequality. As a result, there are now only 850,000 industrial jobs in the territory of the former DDR, four to five times fewer than there were in the DDR. In the agricultural sector, the land taken over by the Trust Agency gained the attention of speculative buyers around the world and local farmers were unable to afford the rising land prices. Agricultural companies from West Germany and other EU countries now own this land.

In order to counter the persistent myth that the DDR was bankrupt, it is worth looking at debts in West and East Germany: In 1989, the DDR’s debts to non-socialist states amounted to some twenty billion DM. After German unification, so-called ‘old debts’, which consisted of housing construction loans and internal state budget debts, were included in the calculations of the DDR’s domestic debt. This brought the DDR’s total domestic debt to eighty-six billion DM. Furthermore, in the DDR’s planned economy, companies had to pay their revenues to the state. The state transferred investment funds from these revenues back to the agricultural and industrial enterprises. These transfers, as independent economic units, were internal accounting procedures which were not booked as ‘debts’ in the overall system; they balanced each other out and therefore should not be counted as part of the debt balance. Other socialist states owed the DDR nine billion DM. In summary, the total domestic debt can therefore be estimated at around seventy-seven billion DM.

A comparison with West Germany’s total domestic debt of around 475 billion DM shows that each West German contributed almost two and a half times as much debt to reunified Germany per capita as their ‘poor’ brothers and sisters from the East. In 1989, the DDR’s debt amounted to about nineteen percent of its GDP, while in West Germany debt was forty-two percent of the GDP.

In light of these figures, it is completely unfounded to talk about the bankruptcy or insolvency of the DDR in 1989. The DDR paid both its foreign debt (loans from foreign banks) and its domestic debts (such as wages, subsidies, and pensions) right up until the end.

In 1990, the West German Trust Agency appraised the economic value of the DDR at around 600 billion DM. However, this calculation does not include public property such as water and power plants, mineral deposits, or land, all of which account for a substantial amount of fixed assets. In addition, the Trust Agency took over almost 4 million hectares of forest and agricultural land, which was appraised at 440 billion DM, as well as extensive residential property, wealth belonging to political parties, and mass organisations and other assets. An additional 240 billion DM of state administrative and financial assets can be added on top of the DDR’s total assets in the form of buildings, plots of land, and foreign assets, the latter being worth one billion DM. Putting together all these figures, some of which are only estimates, it is clear that the East held assets with a total material value of some 1.4 trillion DM. That was the true economic value of the DDR.

Selling off the economy unleashed a wave of destruction on the country’s industrial sector that had not been seen since the Second World War. This led to a tremendous increase in wealth for West German corporations and formerly expropriated landowners. Unemployment and structural discrimination caused almost four million (mostly young) people to leave East Germany. The birth rate fell drastically and the dismantling of the economy and of society in general left previously prosperous regions in ruins. Schools, offices, cultural institutions, and public utilities were closed down in villages throughout East Germany. The infrastructure deteriorated. West German politicians had promised ‘flourishing landscapes’, but what grew instead were deindustrialised regions and poverty.

Many citizens soon became disillusioned. Quite a few of them had taken to the streets in 1989 for a ‘better socialism’ with demands for more democracy and the self-confident slogan ‘we are the people.’ The idea that some of the social securities of socialist society could be carried over into capitalist Germany proved to be an illusion, of course; instead, they soon found themselves economically cut off and often in precarious living conditions. Their life achievements were discredited and rendered invisible.

This growing dissatisfaction was exploited by right-wing circles in the old Federal Republic. Right-wing structures had always existed there, often fought only half-heartedly. The ‘vision’ of a re-emerging Greater Germany based on right-wing ideas now found its advocates in much broader circles of society in the course of German unification, while the media and politics put all their efforts into continuously discrediting left-wing ideas after the alleged failure of the socialist project.

The wealth looted from the East also paved the way for Germany to become the hegemonic power of a Europe that to this day continues to treat workers from Eastern Europe like second-class citizens, systematically put Africa at an economic disadvantage, and literally drown people at its external borders. It is important to fight against this imperialism but also to recognise where it comes from and what alternatives might be possible. The history of economic development in the DDR, for example, shows what is possible under socialism – even under adverse conditions.

The economic efficiency of the DDR and its achievements in the field of social policy briefly described here will be elaborated on in future studies with concrete examples of what policy and daily life looked like. These historical achievements can inspire new ideas on how to create a just world as we address today’s pressing challenges. In this way, experiences from the DDR can be put to practical use from their historical context in order to better face the irreconcilable contradiction of living a dignified life in a capitalist society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Badstübner, Evemarie (ed.). Befremdlich anders – Leben in der DDR [Strangely different — Life in the GDR]. Berlin: Karl Dietz Verlag, 2000.

Blessing, Klaus. Die sozialistische Zukunft. Kein Ende der Geschichte! Eine Streitschrift [The Socialist Future. No End of History! A polemic]. Berlin: Edition Berolina, 2014.

Bollinger, Stefan and Reiner Zilkenat (eds.). Zweimal Deutschland. Soziale Politik in zwei deutschen Staaten – Herausforderungen, Gemeinsamkeiten, getrennte Wege [Twice Germany. Social Policy in Two German States – Challenges, Commonalities, Separate Paths]. Neuruppin: edition bodoni, 2020.

Bollinger, Stefan and Fritz Vilmar (eds.). Die DDR war anders. Eine kritische Würdigung ihrer sozialkulturellen Einrichtungen [The GDR was different. A critical Appraisal of its socio-cultural Institutions]. Berlin: edition ost, 2002.

Brecht, Bertolt. Große kommentierte Berliner und Frankfurter Ausgabe [Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt edition]. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1993.

Dahn, Daniela. ‘Zerschlagene Hoffnungen – die Ostdeutschen in der falschen Gesellschaft‘ [‘Shattered Hopes — East Germans in the Wrong Society‘]. Neuruppin: edition bodoni, 2020, p. 313–328.

De La Motte, Bruni and John Green. Stasi State or Socialist Paradise? The German Democratic Republic and What Became of it. London: Artery Publications, 2015.

Ghodsee, Kristen R. Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence. New York City: Bold Type Books, 2018.

Hacks, Peter. Marxistische Hinsichten. Politische Schriften 1955–2003 [In Marxist terms. Political Writings 1955–2003], edited by Heinz Hamm. Berlin: Eulenspiegel Verlag, 2018.

Krauß, Matthias. Die große Freiheit ist es nicht geworden. Was sich für die Ostdeutschen seit der Wende verschlechtert hat [It has not become the great freedom. What has worsened for East Germans since Reunification]. Berlin: Das Neue Berlin, 2019.