Ronnie Kasrils, born 1938 in Johannesburg, joined the South African Communist Party at the age of 23. He was a founding member of the uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress (ANC). After receiving military and intelligence training in the Soviet Union and the GDR, Kasrils helped to establish a sophisticated underground network of anti-apartheid fighters from the mid-1960s onwards. Following the victory over apartheid, Kasrils served as Minister of Water Affairs and Forestry (1999–2004) and Minister of Intelligence Services (2004–2008) in the ANC governments.

The IF DDR had the opportunity to interview Kasrils in Johannesburg in February 2023. He spoke of his own path to communism; his experiences in the GDR, including at a secret training camp for ANC militants on the outskirts of a rural town in north-eastern Germany; and of the impact of the socialist camp’s solidarity with national liberation movements.

How were you politicized and when did you join the liberation movement in South Africa?

I grew up during the Second World War and my background is of Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. My father was born in Lithuania, my grandparents came from that area. We lived in our own little neighborhood (as is often the case in South Africa’s different communities), which was very Jewish. My parents might have been mildly Zionist, but they were more secular, not terribly religious. I, actually, was quite a rebel as a kid and it was because of the South African situation. I just abhorred the racism and the way people treated black people. There was this element of anti-Semitism that existed here, and not just from Afrikaaner with Dutch or German background. The ones who could be even more anti-Semitic were those of British origin. So, one becomes a bit sensitive that way.

My mother had two cousins, both of whom were in the South African Communist Party (SACP). I started picking up little bits from these lovely, quite sophisticated women. One of them married a famous communist who became my mentor later. But even as a teenager, I started reading books of the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War which brought me into a realization of how the Soviet Union had really been responsible for the defeat of Hitler, which went contrary to what we had been told in our English-speaking schools here – they spoke all about Montgomery and the British and the Americans.

Reading helped a lot too. Even anarchistic stuff like Arthur Koestler and so on. This was prior to Sharpeville [the 1960 massacre of anti-apartheid protestors], so I was only about 21 then. I was interacting with black people mostly through music and poetry, while also diving into Bertolt Brecht and literature of this kind. Quite early on I get a real passion for Brecht which begins to take me into the counter culture of Germany against Nazism. I’m writing poems and I get a job in writing film scripts for a film company, which was quite an avantgarde-thing to do in South Africa. But the people I was interacting with across the color line happened to be more Bohemian types even amongst the black people.

Then the Sharpeville massacre struck in March 1960. It hit me so fiercely that I suddenly realized, you can’t just go on having discussions and debates and reading. You’ve got to do something. That’s when I began searching for people who are now in hiding and trying to flee the country. I went to visit my communist cousin in Durban, she is 15 years older than me, and her husband was now underground. He was running away from the police and is organizing from underground. I was not known to the security police at all. It was helpful for the communist movement to have someone they could trust and who could run as a messenger, which is what I became.

To cut a long story short: My understanding developed incredibly during discussions with my cousin, who gave me such deep insight into Marxism, into the Soviet Union, and into the Second World War. The Cuban Revolution was also unfolding at that time, so I was caught by the bug now. I became very involved with the underground, with the ANC, with the Communist Party, and with the armed struggle. Being young and very physically fit, they seized on me to carry out these military operations.

Having come from that Jewish background, I was so interested to understand the rise of Hitler and how fascism had come to power in a country where the working class and the Communist Party were so strong and well organized. In relation to that, I acquired a realistic understanding of capital, class forces, and how fascism arises. I began to absorb all the classics and debates which were taking place within the liberation movement as well.

How did you first come into contact with the German Democratic Republic (GDR)?

I was in exile and working in Tanzania for a couple of years after 1963 and it was there that I first established close contact with the GDR through its embassy. The ambassador [Dr. Gottfried Lessing] was wonderful. He was unfortunately murdered alongside his wife in Uganda by Idi Amin. I remember him so vividly. In Tanzania, there was a small GDR delegation with just a few people, Dr. Lessing and his wife, and a couple of others. They were making quite an impact on the liberation groups which were now centered in the capital Dar es Salaam, and they held good relations with the Tanzanian government. I can remember Dr. Lessing saying how they were striving to get their work done but they were having to rely more or less on their own. They had the will, but they didn’t have many resources. Still, this delegation became a magnet for those engaged in the liberation movements, they made a very big impact. In talks they would explain the origin of the GDR, the whole nature of the situation, and how the GDR came into existence, what East Germany was up against. We immediately could realize that West Germany and the West wanted to see this young socialist country absolutely wiped out. One began to realize how important the solidarity we were receiving from them was as they had only few resources. We began to realize that, as liberation movements, it was our duty to understand the whole nature of Germany and the GDR, its existence and development.

Within a few years, I was deployed to London and I had the privilege to work with people like Yusuf Dadoo. Incidentally, his former wife had been married to Dr. Lessing, the GDR ambassador in Dar es Salaam. She had been a German woman who was living in South Africa from before or just after the war and was an anti-fascist. Dr. Lessing, a tall bespectacled guy, always optimistic and with a great sense of humor, always knew that we had to deal with the problems and the contradictions. He was a great ambassador – in the general sense, not in a formal – for a new socialist Germany. He really impressed young people like myself and had very good connections with the older people like Oliver Tambo and Moses Kotane and leaders from other liberation groups.

Quite soon after, I was in Britain. I was deployed there, and we began to create clandestine connections with South Africa and recruiting couriers. My book, International Brigade against Apartheid (2021), is about the recruiting of young white people, especially from the Western countries, who could easily go in and out of South Africa. I used to read books about the war, as I mentioned, including the “Rote Kapelle” [German resistance group against fascism – editor’s note] and these kinds of books about how the underground operated. It was quite amazing to discover that within fascist Germany even after the onslaught against the communists and socialists there were still groups brave enough to operate. There was one that came out of middle class or bourgeois circles; it was called the “White Rose” and I was reading all about them. These were the kind of books that one was becoming very interested in, so I had quite a good feeling about German progressives and obviously the communists, who were against Hitler.

There were some Jewish comrades, some younger people who I had recruited, who even at that time still found it difficult to work with Germans. For example, when we were working with GDR delegations in Maputo. They didn’t differentiate between the Germans and said “Ronnie, he’s from Germany, I don’t know if I can meet with him”, and I’d say, for goodness’ sake, don’t you understand the difference? It’s like in South Africa: people are for or against apartheid.

My first experience in the GDR was around 1967 when I went there with Joe Slovo [a leader of the SACP, from 1994–95 Minister of Housing of South Africa] to solicit some support for training programmes. People from Tanzania and Zambia were already receiving training through clandestine activities in the GDR, and they also benefitted from their skills in smuggling literature and carrying out underground work. That was my first visit. Going there gave one an absolute understanding of the extent of the solidarity which the GDR was providing.

What kind of training and support was the socialist camp providing to the liberation movements?

I had been trained in 1964 for a full year with a contingent of 150 other comrades of our armed wing. We subsequently trained for a year in the Soviet Union, and we came to appreciate the resources, the extent of the power of the Soviet Union. The Soviets were able to provide military and non-military training to hundreds and hundreds of fighters, alongside weaponry and other resources. Some of our comrades were trained in Algeria and in Egypt at that time; in one year, they fired their weapons maybe three times. In the Soviet Union, we were firing our weapons every day during practice. Those were the kind of resources they had.

Suddenly, one was in a small socialist country with this huge aggressive neighbor in every sense of the word. We could actually see that even in 1967/68 there was more development taking place than one was seeing in the Soviet Union. Of course, this became clear later on, but the GDR’s readiness to support us amazed me at the time. And they were providing this kind of assistance to other national liberation groups as well. While we were there, we encountered comrades from Namibia, from SWAPO. There was quite a connection, because Namibia had been a German colony with concentration camps – the first concentration camps in the early part of the 20th century – set up by the German Empire which committed a genocide there.

We were discussing the possibility of training the people who had been based in London. I came to realize that Mac Maharaj [SACP member, from 1994–99 Minister of Transport of South Africa] had a very strong connection with the GDR. He is a prominent South African who had been trained in the GDR, particularly in printing and using underground methods from early 1960s. He went back to South Africa to work in the underground in 1962. After the Rivonia Trial, Maharaj was arrested and served 12 years in prison.

So as early as 1960, the GDR was inviting some of our people based in London and providing them with training in non-military and clandestine activities such as the publishing of underground materials. I had the privilege of watching the growth of the resources going towards assistance for the national liberation struggle, from the 1960s right through to the late 1980s. And I was, of course, involved in Teterow.

Teterow [a town in north-eastern Germany], from 1976 onwards, became a center in which the small GDR would provide six-month courses twice a year for 40 very advanced ANC cadres. They received high-level guerrilla warfare and underground clandestine training, including security and intelligence preparation. Other groups received their training in different safe houses in East Berlin and its environs. Maybe four or five people a few times a year, sometimes only one or two, just receiving focused training and getting back into South Africa.

It had grown to that degree. Having been involved in a Teterow training group and going there maybe twice a year over 10 years, my estimate is that we had more or less 80 people trained annually over a 12-year period. That’s just under 1,000 cadres, which is incredible because this was very advanced, highly sophisticated training. One could add a couple of hundred other cadres from our intelligence and security departments over the period of a dozen years, receiving training as well. They probably amounted to just over 200 cadres, plus perhaps another 50 that had been selected from inside South Africa, the latter being very sophisticated and advanced in their political awareness and activity in the emerging trade union and mass democratic movement of the 1980s. We would select and bring these individuals to a place like Netherlands, Britain or France and from there send them into the GDR. They received very concentrated and focused preparation training over two to three months in relation to underground organization, linking with the public levels of organization, learning aspects of self-defense, security, sabotage techniques and so on.

“The GDR – being so close to the West and having to interact and contest with the West – had a much more sophisticated grasp of the power of capital in the imperialist states.”

The other element of the training that the GDR provided, as started with Mac Maharaj, was running an underground press. But also the provision of our magazines and material and small booklets which were disguised with false covers. They printed for us our journals like the African Communist, and for the ANC their main journal Sechaba. This was all organized through London via both the editors of Sechaba, “MP” Naicker and later on Ben Turok, and Brian Bunting from the African Communist as well as Sonia Bunting. She would be going back and forth to Berlin with the texts for printing, the arrangement for dispatch of the thousands of copies of those journals through to London.

You can imagine the extent of the capital resources provided for that – totally dedicated to liberation movements around the world and Africa featured very much. It wasn’t just the examples I cite for the South African movement, but it was for the others as well. In 1990, when Namibia becomes independent and the GDR actually is kaputt, its president, Sam Nujoma of SWAPO, is invited to the Federal Republic of Germany. He goes to Berlin and they had a program worked out for him. He looked at the program and the dear man who showed his nobility and his understanding principle, he said to the Federal Republic of Germany, before I start your program, the first thing I have to do, which you don’t have on the program is to go to the eastern part of Berlin and to see the people who were assisting us for all these years and to pay his respects. And you can imagine how taken aback they were! But it’s an example of how the GDR helped, in practical terms of assistance, material assistance.

By the way, we also received clothing for the military: uniforms from Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and the GDR. A lot of our people were in GDR military uniforms in places like Angola and Tanzania. We received food and civilian clothing as well, right through this period, from the mid-1960s, right up until, unfortunately, the demise and the collapse of the GDR.

One can go on giving examples but I’m just citing them, so that people can understand the extent of that support. And it went beyond the actual material support, it included diplomatic and ideological aspects as well. At Teterow we had, for instance, a professor from a nearby university town. I remember having interactions with him about what contradictions the GDR was facing and so on. The high level of the theoretical presentation, ideology and philosophy was really very impressive. The GDR – being so close to the West and having to interact and contest with the West – had a much more sophisticated grasp of the power of capital in the imperialist states. It could alert us to understand the extent of this. So, it was a very profound relationship.

What was your impression of socialist society in East Germany?

In the first place – whether it was the GDR, Cuba or the Soviet Union – we basically interacted with the authorities who were wonderful in all those countries. This idea of ‘Stalinist’ and ‘bureaucracy’ and ‘cold people’ – it was the actual opposite. The first time you go there you’re interested about these people and you found not only how human they are, but witty and warm and caring. So, that’s the way as a human being you see through propaganda and the poisoning of one’s mind.

We would certainly see the extent of the development taking place and that this development was absolutely focused into the uplifting of people and of overcoming economic problems even in a place like the post-war GDR. I can remember being taken around to Alexanderplatz [East Berlin’s city center] and a young woman was telling me, how she had been mobilized with other people after the war and voluntarily came to the area where they were clearing up the debris which was right at Alexanderplatz. We obviously could receive this information in class and with officials, who we interacted with, but to speak to a person more or less my age roughly 30 years after the war who was 16 years old in 1945 was very interesting.

One could see more of the sophistication in terms of development industrialization and light industry in the GDR compared to Cuba and even the Soviet Union. We’d always be given a stipend. As a writer and someone they wanted to interview on radio, I always made some Deutsche Marks or roubles. So, I had a little bit of money to spend and from going back and forth to my family in London, I would always find that the shops in the GDR certainly had more improved goods than one would find in Moscow. Not to belittle what was happening in the Soviet Union, but one could get the impression that socialism was advancing more in the GDR.

I was fortunate to interact with some South African students while I was in the GDR. I visited Teterow but then would have some time at the Gasthaus an der Spree [“Tavern on the Spree River”], which was a party hotel. Being very free to go out into the city and to get into the underground trains, hardly paying a penny, and going anywhere was absolutely amazing. I was then able to meet ordinary civilians, younger and older people.

Experiencing everyday life, you did come across both pros and cons, which made it interesting. Because it’s impossible – and we weren’t naïve – for a country to become advanced while being cut off from the international market to a such a degree, virtually sanctioned. We were well aware of these tremendous problems. Also, the issue of being eye to eye with a very aggressive, vengeful, powerful West Germany which had taken into its political elite, its ruling class, and judiciary former Nazis.

Sometimes, when we interacted with younger people in the GDR, they weren’t seeing this side of things, not as much as their parents. They would be very interested in the freedoms in the West. They would be saying, “Here it can be a bit boring. At work we’re under such structure and people are a little bit wary of being critical”. Sometimes it was also real gossip, which I would laugh at and argue about with them. They hear that Honecker and the rulers would be receiving fresh milk from Denmark every day and – because I was at Teterow, which is in the countryside and we were paying visits sometimes to particular farms – we saw such glorious farm animals including cows being milked. I could laugh and say, what is wrong with you guys? Be very careful about Western propaganda! It’s designed to undermine your belief in the system. You don’t know what these people are up to and I used to tell this to people in the Soviet Union as well.

We had a wonderful South African comrade, Arnold Selby, who worked for the GDR radio. He had a big contradiction with his wife and young daughter because they would tune in to West-Berlin television and he never in all his life in the GDR would even look at an image on the screen unless it was a channel of the GDR. He used to have very serious discussions and arguments, because they were attracted to it and of course he was so highly principled and understanding the imagination of this false propaganda.

Living next to West Germany, it was impossible to keep aspects of this kind of propaganda and that inevitably when you building a new society you have particular problems and people can become very subjective about such things and begin to interpret things in a wrong way. I’m not saying that, as time went on and we came towards the end game which affected so many people, that there were not deep contradictions. But if one had a big picture view and an understanding of the international situation and what was now taking place vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, we could see this happening.

I trained in the Soviet Union for military intelligence in 1983 and I was quite shocked at the difference in the presentation that one would receive from our instructors. At the political level there were sometimes quite silly presentations about the international situation. I can remember when this one commissar was talking about the growth of socialism and asking how many socialist countries there were. I had quite an argument because although he was numbering of course Vietnam, but also Laos and Cambodia but not Mozambique and Angola. I said, you include Laos and Cambodia which don’t have the productive basis and kind of communist leadership of Vietnam, and yet you keep out Mozambique and Angola. The guy then proceeded to say, and what about San Remo in Italy? I said, what are you talking about? He was counting one of these other little places where communists united in small parts of France or Italy and got a majority in terms of the council that year. I was there with a group of people not as sophisticated in understanding of me and I had to say, look for goodness’ sake, he’s giving the wrong impression here.

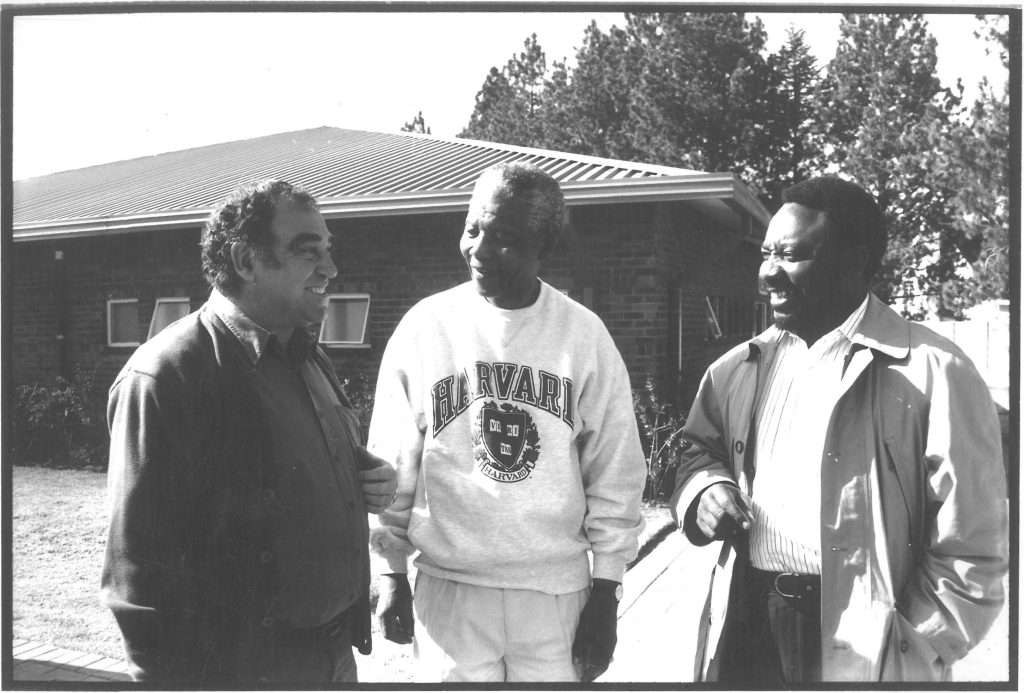

Coming back to the GDR: At the intelligence level there was a man called Markus Wolf, a great hero of yours and of the liberation movements, who had played such an important role in ensuring that our people received that type of training as well. That was very sophisticated stuff comparing it to the Soviet presentation. We got very good ideas and very sophisticated ideas about how to collect information through Markus Wolf. A few years before he died, he came to South Africa to meet amongst others Mac Maharaj. A little party was thrown for him. People throughout the national liberation struggles were very aware of the value, the extent, the camaraderie and the warmth of the support that we received from the GDR.

What was the theoretical basis for this solidarity between the socialist states and the national liberation movements or the newly independent states?

The basis of the communist ideological underpinning that we received in South Africa and that gave birth to this internationalism and this unity emerged after the Bolshevik Revolution with the establishment of the Communist International. Right from the beginning, the whole theorization out of Marxism, of the alliance and the solidarity between the socialist countries and the anti-colonial struggle – what we called the three detachments of the struggle: the socialist camp, the working class of the capitalist countries, and the national liberation movement. And we held big discussions around these theories. The Communist Party of South Africa was very involved in those debates from the early twenties and the consequence of those debates of how the formulation of anti-imperialist struggle, the anti-capitalist struggle, the alliance between socialism and the people fighting against colonialism and how hard to develop that unity. Out of this emerges the firm unity of such forces.

The theoretical factor is vital in terms of what people from the so-called Third World received, especially post-Second World War. There’s the theoretical understanding and analysis as well as the support received materially and practically in the struggle against colonialism and the collapse of the colonial system. This support was provided for the emergent independent countries such as Tanzania, Ghana, Egypt etc. or in the hours of need like at the time of the 1956 Suez crisis with Britain, France and Israel taking control of the Suez Canal. These aspects including economic development and possibilities of these countries against neo-colonialism. All this underpins our understanding of what proletarian internationalism is and the unity that is required between the three detachments of the struggle. We then went through the phase of the Sino-Soviet dispute, which created certain confusions, but also greater clarity.

“Comrades, solidarity is a two-way street. It is not just that we come here from South Africa and we receive solidarity from the GDR or the Soviet Union. It is what we can also provide them: they require this steadfast support, this alliance – for example, through the ‘non-aligned movement’ which is progressive and anti-imperialist, which the socialist countries support and don’t simply see as neutral between two camps.”

The same comrade who was working with Radio Berlin, Arnold Selby, he used to speak with the South Africans and talk about his actual experience in the GDR. He was an ideologue, a theoretician. He was a very practical guy with a white working-class background in South African trade unions. He used to say: Comrades, solidarity is a two-way street. It is not just that we come here from South Africa and we receive solidarity from the GDR or the Soviet Union. It is what we can also provide them: they require this steadfast support, this alliance – for example, through the ‘non-aligned movement’ which is progressive and anti-Imperialist, which the socialist countries support and don’t simply see as neutral between two camps. But we must understand, how we must support them in the world bodies like the United Nations, to break out of the isolation and the sanctions, which the West is constantly attempting to apply. And how we must work and assist these comrades in Africa. They are not simply there to give us support but they need the kind of support from us to break out of isolation, because we have our GDR comrades in those countries and towns feeling very isolated and we must make sure that liberation forces attend the events they put on for us.

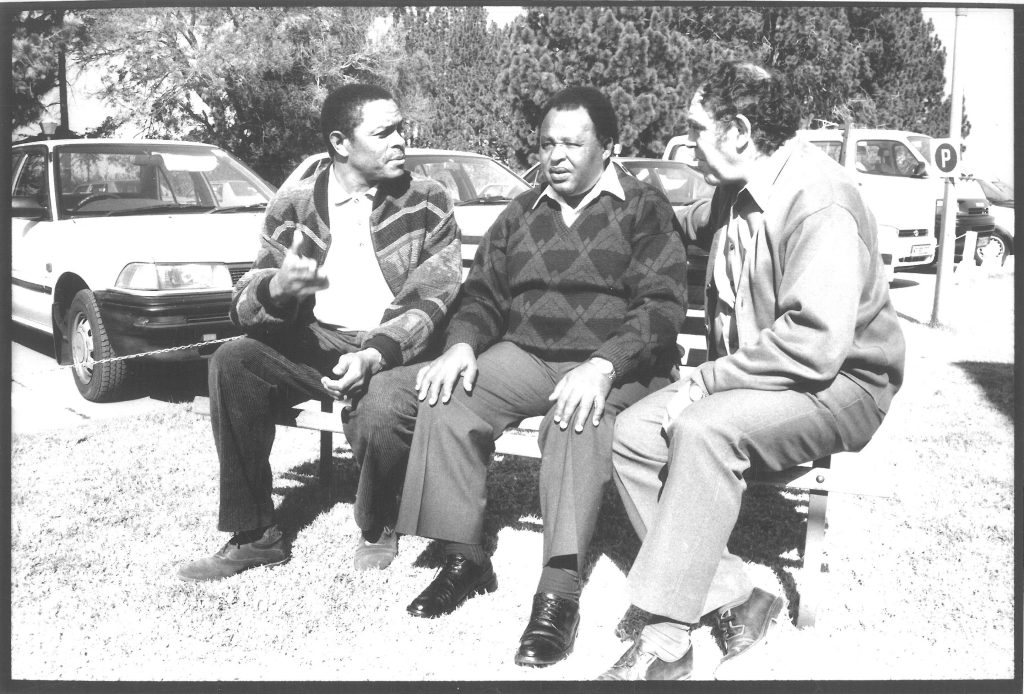

When Tanzania became independent in 1964, there weren’t many GDR embassies around the world. By the 1970s there were many more and they were more confident, they had more resources. In Zambia, the comrades from the embassy were giving us such support. We could visit them and we’d be welcome there. We could use their phones to speak to our people in London, France, and in South Africa. Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki also came there, and the embassy took us home, not to their headquarters, where we often used their phones to talk to Winnie Mandela. We had long conversations trying to direct her in her activities.

Such gestures were very touching. They sound like small things. Do you think you could get something like that out of the British, the American or the French embassies in those countries? You wouldn’t even dream of asking for such assistance. Would you ever be really welcome in those places? Obviously, as time went by and we were getting on top in the struggle, then the West started inviting us to their embassies. We would only send people to go there, who were from our intelligence structures, to keep very tight-lipped and sort of pick up what was going on in places like that.

There’s the question of the difference between what we received from all the socialist countries – and I’ve always pointed out how the GDR, being really amongst the smallest was up there with the Soviet Union and with Cuba. Unfortunately, with China for this very long period of exile up until independence in South Africa, until freedom, the Sino-Soviet dispute had affected that relationship. But the GDR was absolutely solid right through all those decades of the 1960s to the end of the 80s. The Western countries were working against us. They were supporting apartheid. They were calling us terrorists. They were providing apartheid with impunity. It didn’t get to quite the degree of the USA and Israel, because apartheid embarrassed the Western countries and therefore, they would put up some hypocritical mask in relation to that. We know of Harold McMillan talking to the South African racist parliament in 1960: “The Winds of Change are coming to Africa”. But that was to encourage the apartheid regime not really to reform it. It meant that things were changing and that if they went out of line as they did with Sharpeville, there would be condemnation. But this was never of the kind that brought any real pressure even in the practical sense of the isolation of South Africa. Far from it, because South Africa sought an alliance with all those Western countries in relation to the bogey of communism in the Cold War. This is where the regime would then raise the anti-communist issues in order to show that they were a reliable ally of Western capital.

How did you experience the end of the GDR and the wider socialist camp?

The collapse of the socialist camp, starting in Poland with Solidarność in the 1980s, or even going back to the Prague Spring of 1968, actually affected me. I was very solid in terms of how we understood the Soviet Union etc. I had been raised as a younger person in London with people like Dr. Yusuf Dadoo, Joe Slovo and the top leadership. I had been quite disturbed, because suddenly we saw major contradictions. It wasn’t so much an external intervention like that of a color revolution. It was clearly coming from the street level with students very much involved. So, I could see some elements of what I’ve been mentioning earlier in the GDR fairly recently before that. But it was quite disturbing to see such numbers, which, in the GDR, only started to emerge at the end of the 1980s around Leipzig. One always looked for Western interference though, which was always there.

Perhaps in those periods of the 1960s, we weren’t so clear about the extent to which the USA and the West had been attempting to undermine the socialist camp. Being from the Markus Wolf background, I was very interested in the writings of people like Kim Philby and others. You would read and sort of toss it off as though it wasn’t so important that Britain and America particularly had been parachuting people into Albania and the Balkan countries, as in Ukraine today. You just thought, oh well, this wasn’t much of a problem. It was like reading a paragraph in a book and not realizing its depth.

Regarding Czechoslovakia and the Prague Spring, I can remember in the big debates we were having in the South African political milieu in London at that time. The older comrades like Yusuf Dadoo were saying: No, you must see the extent to which the imperialists want to take over Czechoslovakia. Palme Dutt, who was one of the outstanding theoreticians of the British Communist Party, wrote an article which then changed my thinking. It said that Czechoslovakia was a dagger at the heart of Moscow, and he then highlighted what hadn’t been so obvious: the extent of what was happening in the GDR, the imperialist’s intervention, the establishment of groupings and collaborators, obviously always starting with spies and espionage. So, one was very aware that the socialist camp couldn’t lower its guard and had to keep up a high state of vigilance and therefore security control à la Stasi. We know how these things are also exaggerated in the West even in relation to say, Stalin’s rule where we see the equation of Stalin and Hitler equaling Putin and Hitler, which is a very powerful narrative if you don’t have a counter to it, when you are subject to Western disinformation through the television, media, and academia.

So, in your view, why did the socialist states allied to the Soviet Union collapse? And, against this background, how do you understand current developments in the world?

Well, one factor was the question of the degree to which democracy was really developed amongst the people, as Joe Slovo wrote in his pamphlet “Has Socialism Failed?” (1991). He’s not talking about the bourgeois concept of democracy. We’re talking now about a Marxist-Leninist concept of democracy, which you can only have if you can base it on real deep education, theory and understanding amongst the people. Very much to start with amongst the layers of your own authority and party and then into the levels of your people. We saw, how the socialist countries have made huge endeavors in terms of development of new pedagogy, new forms of education at school level. I can remember from 1964 Soviet Union and visiting schools and being so impressed with the awareness of 15 and 16 years-olds in the way they were reading the novels and history of Western countries from Shakespeare to so many other progressive writers.

Apart from the GDR, where I found leaders to actually be very clued up, the interaction I had with leaders in quite a number of other socialist countries was not so deep. One has to, of course, take into account the fact that so many communists had perished in the Second World War. I came to realize something that Joe Slovo, who he had visited all these countries, had told me long ago: “Some of these people are not communists, Ronnie, like you and I are.” That troubled me initially, and I had to discuss it further with him. He was referring to the fact that post 1945, if you looked at a country like Hungary, very few of the pre-war communists had survived. Their parties were quite small and there were a lot of opportunists and careerists, maybe some positive aspects to them, who came in to take up jobs. Yet, they weren’t the kind of real educated communists with a real understanding. We saw this in South Africa too, and in other countries of the developing world, where the national liberation movements had won power. I’m talking here about Mozambique, Angola, South Africa and so on. People came and joined these parties or movements, not always for the same reasons as the old-time Bolsheviks. That makes a very big difference.

That’s a question that arises for the socialist project: How do we build and protect the gains of a revolution which is under such threat externally that you have to have so-called, I say so-called, “Stalinist measures” in place to deal off externally and even with internal subversion, because they carry on with that. You don’t often have the Markus Wolf type of sophistication and I can tell you, he’s very unique compared to the kind of people who I interacted with running intelligence inside the Soviet Union. We see what happened then to the Soviet Union post 1990–91 through Gorbachev and Yeltsin and then neoliberalism.

So, Slovo’s pamphlet about the need for democracy within such societies and to keep their democratic spirit within the party becomes a big challenge in terms of rebuilding the socialist project. Has it got potential? Yes, it has, because imperialism, international capital, is facing inherent internal and unresolvable contradictions and is trying to deal with them in very extreme ways including in terms of how, especially U.S., the EU and NATO, are dealing with China and Russia. Both of these countries are seeking to develop their economies and their trading abilities on the world stage which clearly the USA – given the nature of capital, corporate capital, finance capital and internal contradiction – doesn’t want. When you examine the way they deal with their own people – their workers, the ethnic groups, the black population etc. – we see how vile this rule is and how vicious they are in holding on to the empire and imposing their hegemony, keeping it imposed, because it’s under such threat.

So we begin to see a phenomenon and new developments: The West is shocked that, when they blew the whistle for support for sanctions and condemnation against Russia, the world didn’t come running to their doorstep. Although they claim that the majority, 140 countries, in the U.N voted their way, they forget to actually use arithmetic and total up what India and China actually count as, what Brazil and South Africa and Indonesia and even countries like Saudi Arabia and so many in Africa count as, who are refusing to cater to the Western line. Of course, it’s very difficult to prophesy what this outcome is. It’s a very bitter struggle. Russia is having to defend itself for obvious reasons in an existential way in the history that it’s been through and the provocations from the USA and NATO in its expansion.

One would loath to see the writ of Washington imposed on the world. Because when we look at this, we see an actual cycle taking place. Is it simply coincidence that at this point in time from the Baltic to the Balkans along the very borders running along the Russian boundary, in all those countries which were actually part, except for Poland, of an axis under Nazi Germany, are now under NATO? I actually say, apart from Poland, but if we look at Poland’s history: It came sandwiched between Germany and the Soviet Union and the particular pact, again a pact not because Nazism equals Stalinism, but because of the geopolitics and how the Soviet Union was perceiving the way Poland was the “dagger” through to Moscow. We were well aware of how reactionary Polish nationalism has been right through the centuries and how ultra-reactionary it is today as part of Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, particularly those Baltic states, Poland and then Ukraine.

I’m just saying, what is it then about this axis and this alignment and the fact that – I’m not saying it’s exactly correct but it’s quite interesting – that the axis under NATO takes on board not just so-called liberal bourgeois democracies of Europe but the most ultra right-wing, neo-fascist countries from the Baltic to the Black Sea. There is the same basis for this. When we look at Europe, the USA and the battleground that Europe has been for multiple centuries, including the two world wars, we see that it is focused the East, especially by the central states like Germany and those of Eastern Europe, looking into the vast lands and the resources, the world’s richest resources, of Russia, which from the time of the Swedes and the Lithuanian and Polish empires were looking in that direction. Of course, we understand that Russia now is a capitalist country, but under this kind of clash, what might emerge, because Russia is showing its strength and there is the alliance with China and the developing countries of the Global South which are not meaningless. They are very important in terms of BRICS, and now that we have Lula in power in Brazil it gives it even greater progressive nature.

So, there is now a huge confrontation underway. What we have to bear in mind in terms of South Africa’s position and so many of the African countries and those in Latin America, and Asia, is that non-alignment is a key factor for us. We won’t be drawn into the axis of Washington and Brussels. The crucial importance now is for a diplomatic negotiated solution – which the West and NATO don’t want. They prevented Zelensky from that, they’re putting the whole world at peril, at the age of possible nuclear confrontation. So, it is a very dangerous time and it requires the international solidarity of progressive forces in the world.