25 April 2024

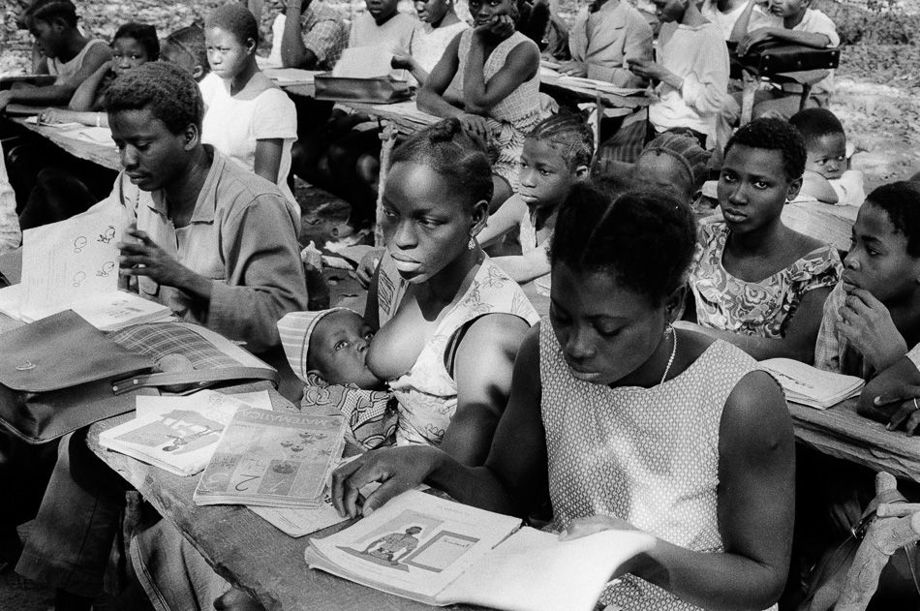

Born in the mid-1950s, Mamadu1Name changed upon request. grew up in Guinea-Bissau’s coastal region of Tombali under the long shadow of Portuguese colonialism. As a child, he witnessed Portuguese raids on his family’s village and the armed resistance of the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), a Marxist-inspired liberation front founded by Amílcar Cabral and his comrades in 1956. In the 1960s, Mamadu received an education through the school system set up by the PAIGC in the areas it had liberated. There, he first came into contact with the German Democratic Republic (DDR), for the mathematics textbooks used by the PAIGC had been produced in cooperation with socialist East Germany. At the age of 16, Mamadu then travelled with several schoolmates to the DDR, where he studied agricultural mechanics and engineering.

We interviewed Mamadu in February 2023. In the following, we share excerpts from our conversation in which he talks about the history of Guinea-Bissau, the effects of slavery and colonialism on his society, and how the national liberation struggle in the colonies was interconnected with the Carnation Revolution in April 1974.

What led to the colonial subjugation of Guinea-Bissau?

The region that is today the state of Guinea-Bissau had been inhabited by the local peoples for almost 3,000 years. But this history is hardly ever found in the textbooks.

From 1441, the first Portuguese adventurers — not “explorers” — arrived in the region and established contact with the indigenous population. From around 1450, present-day Guinea-Bissau was one of the first places where the Portuguese built their trading bases. In the beginning, Portugal was actually the sole ruler of the entire Guinean west coast. The French arrived later and began competing with the English and Dutch for the land. After the Berlin Conference of 1884/85, France and Portugal signed a treaty dividing up the territory. A large part of West Africa went to France, while Portugal remained firmly installed in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau.

From 1895 to 1936, there were major armed conflicts. Guinea-Bissau has 21 different peoples or ethnic groups — I don’t use the word “tribes” — and the largest 5 or 6 ethnic groups put up resistance. France and Portugal played the ethnic groups off against each other and were thus able to subjugate the people more easily. From 1936, Portugal took control of the country and was able to extend its colonial rule over the entire country. From the beginning, the Portuguese brought Cape Verde and the current territory of Guinea-Bissau under one administration.

How did this European domination influence the development of Guinea-Bissau?

Transatlantic slavery introduced a significantly new dynamic that derailed the ’normal’ rhythm of development in our society.

It is true that the Europeans found a pre-existing slave system in Africa. But it was in no way comparable to the transatlantic slave system. In the African empires, captives from war were to work for their captors. The captives were subordinated and put to different tasks, but they were not depersonalized. They were traded, but they remained within their geographical territory — they circulated here. And this system only affected working-age individuals.

Transatlantic slavery, on the other hand, led to the bleeding of Africa. The workforce was exported en masse, and this led to social regression: knowledge was not passed down, technology was not developed further, labour power was missing everywhere, and social structures were dismantled. In the end, the maldevelopment caused by the European slave trade was so great that the effects can still be seen today. This is too often not taken into account in the analysis. It wasn’t just direct colonialism that harmed us.

It was a huge disaster. The hegemonic encounter between Europe and Africa led to domination and exploitation instead of cooperation and collaboration.

How did the African Independence Party of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde (PAIGC) come about?

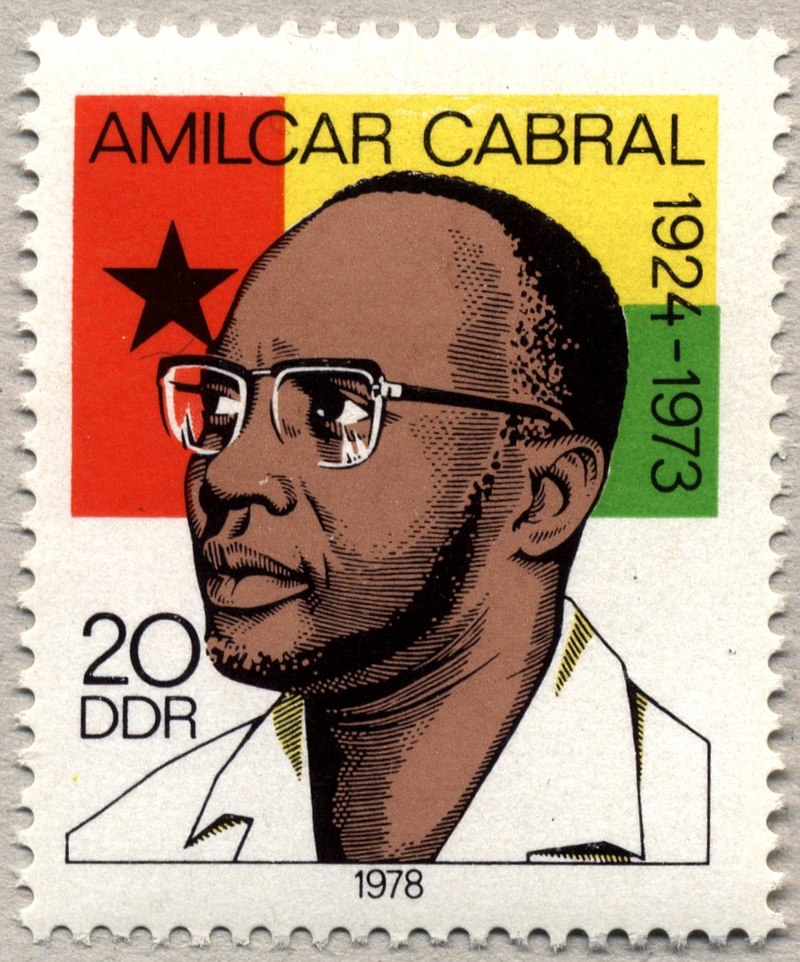

It is precisely in this context of colonial division and oppression that the PAIGC emerged. The agricultural engineer Amílcar Cabral founded the party on 19 September 1956 with two other comrades. Interestingly, Cabral’s parents had been teachers of Cape Verdean descent. They were sent as teachers to Guinea-Bissau, not even to the capital, but to the interior of the country, where Cabral was born on 12 September 1924. A noteworthy aspect of the party was that from the beginning it campaigned for – as it is called – “African independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde”. Pan-Africanism was built into it from the beginning, but not as an abstract Pan-Africanism without territory. There was a concrete reference to Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde as the regions in which this struggle was to be taken up. I too am a product of this process.

What is your personal background? How did you come to the DDR?

I am from the south of Guinea-Bissau, from a relatively large village by Guinean standards. I was born in 1955 and first came into contact with Portuguese soldiers in 1962. They had surrounded us and there was a lot of commotion. For us children it was like a happy day, we ran out curiously to the cars and soldiers. But it was bad. There were many arrests in the neighboring village; an uncle of mine was also arrested and taken to the concentration camp in Tite near Bissau, as I later found out.

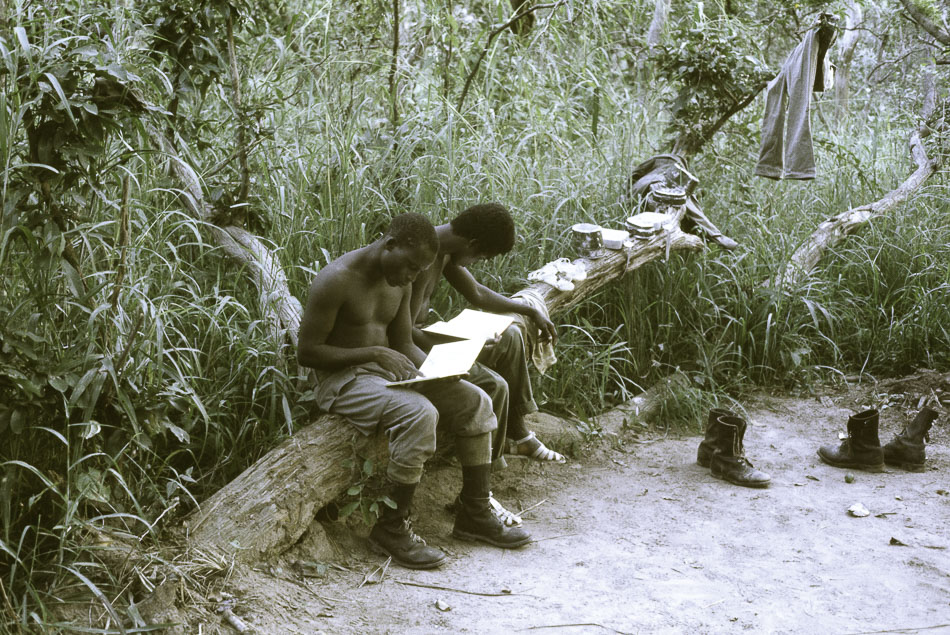

This first contact with the soldiers had a huge impact on my life. Our village was caught in the crossfire: on the one hand there was a Portuguese barracks barely 2 kilometers away from us, on the other hand, PAIGC fighters were camped about four kilometers in the other direction, and they largely controlled our village. The Portuguese patrols kept coming and there were real battles around the village. Afterwards we had to evacuate.

In 1969, I entered the school system set up by the PAIGC in the liberated areas. The best students were selected there and sent to boarding school. First to a boarding school in the liberated areas and then to Conakry, the capital of Guinea. This boarding school operated as a pilot project where the PAIGC tried out new didactic and pedagogical concepts. This is where I first came into contact with East Germany, because the GDR was the country that produced school materials for the PAIGC’s mathematics lessons in the liberated zones. The handover of the first educational materials was held at the GDR embassy in Conakry. A pioneer group was selected to officially receive it. I was in the group and had the privilege of speaking there — I had never dreamed of that!

I was 14 years old at the time and stayed at this boarding school for two and a half years. There was a large offer of study scholarships from socialist countries, and I received a training place in the GDR. So, I travelled to East Germany when I was 16 years old. There I trained to become a tractor and agricultural mechanic.

The socialist countries — the GDR, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and so on – provided direct support for our liberation struggle. We knew these states were our real friends. The end of the socialist camp almost overwhelmed me back then. I was devastated – really distraught! Because we knew that without the help of the socialist camp in the anti-imperialist struggle, there would still be apartheid in South Africa today! There would still be Portuguese colonialism in Guinea-Bissau, fully backed by the Federal Republic of Germany [West Germany] and others. No doubt about it.

You were in the DDR when Guinea-Bissau’s independence was declared. How did you and the other students stay in touch with the PAIGC?

We were always in constant contact with Guinea-Bissau when we were in the DDR. At that time, our party founded a youth and student organization. We held monthly meetings in which we would organize and develop our activities and pay our contributions.

In November 1972, Amílcar Cabral made an official visit to the DDR. He sat with our student contingent for a whole day and discussed with us. He prepared us for Guinea-Bissau’s upcoming declaration of independence. That was in November, and he was murdered in January. This came as a total shock for all of us. At that time, all students sent a joint statement to the party saying that we wanted to go back to fight at the front for the liberation struggle. But we were then told that our mission was to study, so that we could come home with a profession — that was also a big shock.

But it had been seared into our heads: 1973. Cabral had declared it in his New Year’s communiqué: In 1973, we will declare our national independence. And so, 1973 became the most exciting year here — will it work or not? Instead of getting the usual bad news – that the Portuguese were advancing and so on – we bean to receive optimistic updates from March onward: Portuguese garrisons were being overrun by PAIGC fighters, planes were being shot down again, and so on. And then came our unilateral declaration of independence. We celebrated in East Germany. The DDR’s Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee called on us to hold joint events. We invited students from other countries – that was a great experience. And it was shortly after the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students in Berlin. 1973 was the craziest year! We are all celebrating at the Festival in Berlin and Inti-Illimani, the October Club and everyone was singing at the end of the day. And I was there!

After Guinea-Bissau’s declaration of independence, the international stage became very important. At that point, the Portuguese military was on the defensive. And now it got exciting: Will the international community recognize our independence or not? By December of that year, we had the absolute majority of UN countries behind us. So, we knew that Portugal was now beaten internationally – military, political and diplomatic. When we heard that a coup had taken place in Portugal, we knew it was done. This is our victory. And we celebrated the coup as our victory.

When I finished vocational school in 1974, I was supposed to go back home, but because of my good results I was recommended for engineering school. The party approved this and so I stayed in the DDR until 1988.

How was the liberation struggle in the Portuguese colonies connected to the Carnation Revolution?

It was said to be the first time in modern history that pressure from the South was able to bring about the overthrow of a regime in the North. For us it was clear to us: the founding of the PAIGC in 1956 and the start of the armed liberation struggle in 1963 would definitely help to bring down the fascist regime in Portugal.

I later learned that the Socialist and Communist parties in Portugal were very much discussing with the liberation movements how joint cooperation should be organized. Amílcar Cabral made it clear that they must now join our struggle for independence, instead of our people who were currently studying in Portugal all joining the Socialist and Communist parties – some members of our party were also members of the Communist Party of Portugal. The reasoning was that if the fascist system in Portugal falls, then the Portuguese colonies will not automatically fall with it. But, if the Portuguese colonies defeat this colonial system, the fascist government, which had already existed for 40 years at that point, will automatically collapse.

In his writings, Cabral emphasized: We are fighting against one and the same enemy. We have to be very conscious of this. What the PAIGC is doing in Guinea-Bissau is just part of the same fight you are currently fighting — in Portugal, in the Federal Republic of Germany and elsewhere. It is your duty, as a trade unionist in the North, to support the struggles in the South. This is not charity, as is often portrayed these days, but rather an obligation. In Guinea-Bissau, many of us died from Portuguese napalm bombs, but every time we repulsed the colonial army, it was also a victory for you in the North. Through our daily fight in the South, we in fact support your fight. Unfortunately, this understanding has largely been lost today.

In the following excerpt from our interview with Mamadu, he recalls the climactic years of 1972 and 1973, when Cabral visited the DDR and Guinea-Bissau issued its declaration of independence.