A Chilean emigrant and a former GDR citizen recount the victory of Salvador Allende and the Unidad Popular in Chile, the 1973 coup d’état, and the escape from Chile to the GDR.

25 September 2023

Introduction

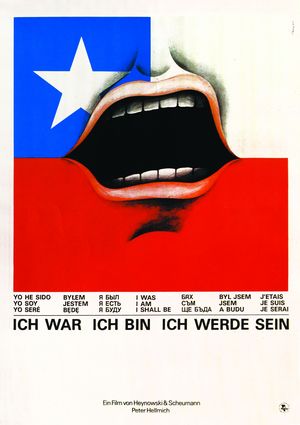

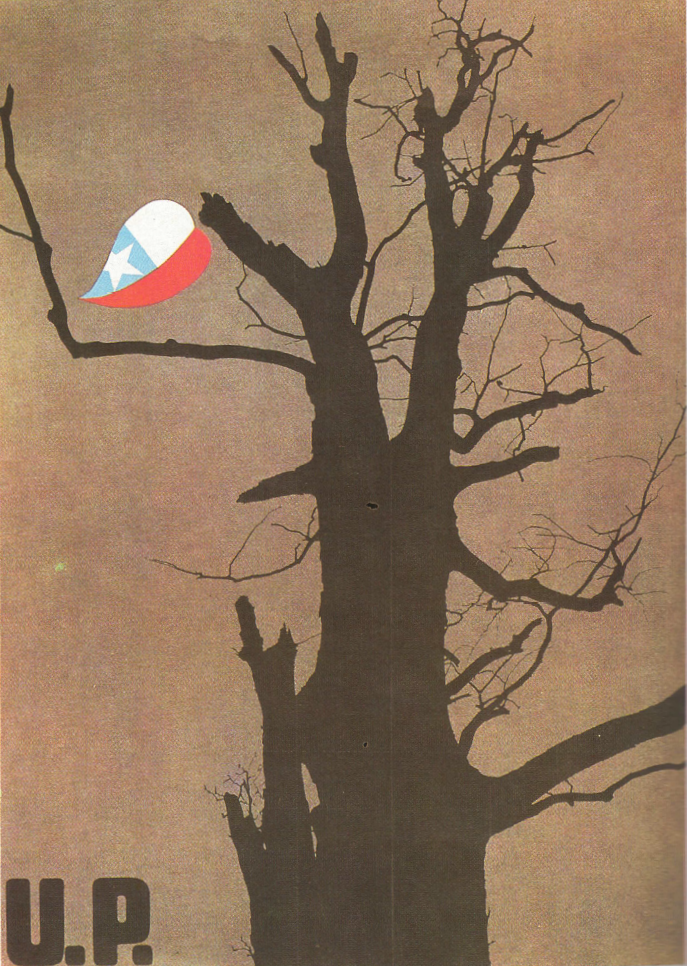

53 years ago, the Unidad Popular (“Popular Unity”) led by the newly-elected president Salvador Allende set out to transform Chilean society. A 40-point programme aimed to eradicate hunger and homelessness, ensure that every child could attend school, and reclaim the country’s natural resources for the benefit of the Chilean people. Three years later, the alliance and its president were overthrown by a military coup d’état led by the US-backed General Augusto Pinochet. There followed an era of fascist dictatorship, in which representatives of all currents of the Unidad Popular were targeted and relentlessly persecuted. Thousands were imprisoned in camps, tortured and executed.

Even five decades years after the coup, many individuals remain missing. At the same time, the true depth of Western involvement in the brutal coup is coming to light. To commemorate the unfinished project of the Unidad Popular (UP) and the international solidarity it garnered, we have recorded the experiences of two women: a Chilean acitivist who was active in the UP alliance and an ardent GDR internationalist who helped exiled Chileans to continue their struggle from abroad. Their stories paint a picture of the atmosphere of the time, from hope and inspiration, to fear and dismay, and finally defiance and solidarity.

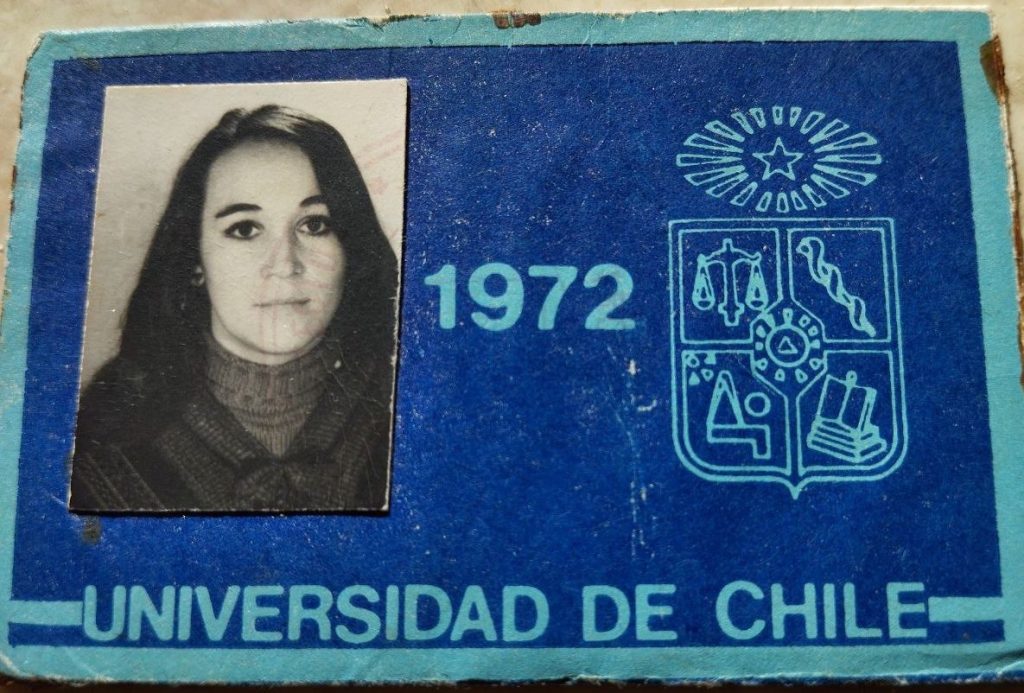

Nancy Larenas lived in the Chilean coastal city of Valparaíso until the coup in 1973. As an active member of the UP party Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria / Obrero Campesino (MAPU / OC, “Movement of Unitary Popular Action / Workers Peasants”), she participated in the implementation of the program of the Unidad Popular, was persecuted after the coup on September 11, and had to flee her homecountry. Her path led her via Santiago to West Germany, then to Cuba, and finally to the GDR. Gudrun Mertschenk, born in 1954, studied history and specialized in the Chilean trade union movement CUT. She was in close touch with many Chileans in the GDR, also through her work at the International Federation of Teachers’ Unions (FISE), where she assisted in organizing solidarity campaigns for the Chileans and was awarded by the “Bureau Chile Antifascista” for her work.

Hope in the Unidad Popular

“I personally and the youth of Chile, under the impact of the victory of the Cuban Revolution, saw that it is possible to take our future in our own hands and not live forever under the pressure of U.S. imperialism.

In the 1960s, momentum came from the democratic movement in Chile, but the conditions were politically different. In 1964, Eduardo Frei of Chile’s Christian Democratic Party was elected president. This government started to implement an agrarian reform, for example. The fact that this went ahead was related to the fact that the 1925 Constitution had some loopholes. And it was through these loopholes in the Constitution that Allende’s government then also brought about a change, for example, through the nationalization of copper and the deepening of the agrarian reform. That was the situation at that time, and we threw ourselves into that movement with all our strength.

But the Unidad Popular had drawn up a program for social justice based on the existing bourgeois democracy. It was a very different approach to the one taken in Cuba. That is, we only won executive power through the presidency, but not the deputies and senators in the legislature, nor the judges in the judiciary, and still less so the military.”

The victory of the UP-candidate Salvador Allende in the presidential elections on 4 September 1970 was indeed for Nancy a symbol of hope, “but we did not have the majority, only 36 percent. That Salvador Allende entered the government was decided in a runoff election in Parliament on 24 October 1970. The Christian Democratic Party, which to some extent still had a progressive side in the agrarian reform, supported the UP first. But later, in the coup, they went along with it. That’s why we say golpe civico militario, because it wasn’t only the military that was involved, but also civilian forces.”

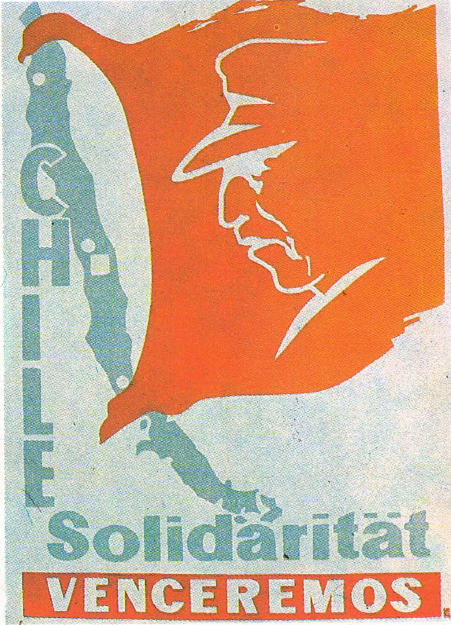

The UP’s election victory was not only associated with great hopes in Chile itself – the entire socialist camp followed the events with great sympathy. Even in the GDR, as Gudrun recounts, there was great enthusiasm: “There were great hopes associated with it, also because the West was always accusing socialism of being ‘bloody’ or ‘undemocratic’. The Cuban Revolution was always denigrated as ‘undemocratic’.” Now Allende and the UP had come to power not through a popular uprising but through the bourgeois system’s own mechanisms. “You know, one would have thought that the Western world would now support Chile, especially since they had just celebrated the 1968 events in Prague and Dubček’s ’socialism with a human face’ so much.” The fact that the UP represented a broad front of progressive forces also gave hope: “In the GDR, too, there was an alliance, the ‘National Front’, in which the four bloc parties and other mass organizations were represented. That’s how it was imagined now in Chile, that there was a similarly broad alliance and that different needs could be served through it.”

Nancy herself was a member of a party inside the UP alliance: “In 1971 I joined the MAPU; it was a split from the left wing of the Christian Democratic Party. It was a small party, these were young people, they wanted more change. In 1972, the party declared itself Marxist-Leninist and split a short time later. I was then a member of the MAPU / Obrero Campesino (Workers and Peasants). As an organization, we had cells in residential areas, in factories, and that’s where I first read Das Kapital. Things moved so quickly – we were in government for 1,000 days, only 3 years!”

After the nationalization of the copper mines by the UP government, the USA stopped its investments and imposed drastic sanctions, which hit Chile as a major copper exporter particularly hard. Foreign exchange shortages intensified, and inflation was rampant. With everything from food production to distribution in private hands, food prices were driven up by buying and hoarding in the emerging black market. In response, Commissions for Supply and Price Control (Juntas de Abastecimiento y Control de Precios, or JAP) were created in 1972 as a structure to ensure food supply.

MAPU delegated Nancy to join one of the JAPs:

“These were neighbourhood-level groups authorized by the government to control prices on the black market, like a ministry. The secretary of this organization was Alberto Bachelet, the father of Michelle Bachelet. He was, of course, later arrested and in March 1974 he died in jail as a result of torture. He had a heart attack. The JAP, together with the cordones industriales [workers’ collectives in the factories], were the seed of democratic development at the grassroots level. The cordones were present in different industries that were in the hands of the workers after the owners had refused to continue production. The workers then defended the factories. The cordones industriales, of which there were about 200, were the second nucleus of popular power, alongside the JAPs.

I became president of the JAP in my neighbourhood. It was a middle-class neighbourhood where many members of Patria y Libertad, a fascist group, lived. We organized the supplies for some 120 families. The members of the JAP – not all of them were communists, there were also socialists and Christian Democrats – put together packages according to the size of the families. We cooperated with the butcher. I went with him to the state meat distribution centre and we took everything to his store. When we went to pick up the goods, we were often threatened by the fascists of the Patria y Libertad, they chased us and tried to mug us.

They also tried to enter the butcher’s shop when the goods were being distributed to take them away, but they failed. We knew that these people — the right-wingers and ultra-right-wingers — had mansions, big houses, and big warehouses. They wanted to stockpile all the goods to create scarcity.”

The situation deteriorates

At the time Nancy was active in the JAP, Gudrun was just 17 years old. She was a member of the Free German Youth and active in a singers’ club. She was fascinated by what was happening in Latin America, had contact with young Chilean communists in the GDR, and had seen the group Quilapayún at the Festival of Political Song, who “gave her a special impulse [to] engage with the Spanish language.”

Gudrun and the GDR population also had learnt from their own experience that a rebellion against imperialism in one’s own country would not simply be tolerated:

“We learnt from our own media that the bourgeois conservative forces, of course, had done everything it could to prevent Allende from taking office. […] Nevertheless, the Congress elected Allende, so he was able to take office on November 4, and from then on there we could follow the continuous reports, not only about the nationalization of the copper mines, but also about the living conditions. Those who followed this closely could really inform themselves about the situation in Chile […] Through this comprehensive reporting, the names of not only figures like Allende, but also of Luis Corvalán, the general secretary of the Communist Party, of course also of Gladys Marín, the chairman of the Communist Youth League, came to be known. Also, in the run-up to the 10th World Festival of Students and Youth, which took place in Berlin in 1973. Culture played a big role. For example, Quilapayún, Isabel Para, […] and Víctor Jara, who had visited the GDR as a relative unknown artist at the time. Other names like Carlos Altamirano, the leader of the Socialist Party, and from the Workers’ and Peasants’ Movement.

The news coverage was very broad. We received reports of all the difficulties that there were, such as the truckers’ strike. That, of course, had a significant effect because of the north-south axis in a country like Chile.”

Back in Chile, meanwhile, the situation came to a head — also for Nancy:

“The contradictions intensified greatly. In principle, we had little power. The coup came on a Tuesday, early in the morning. The previous Sunday, Allende had met with all his ministers and allied parties. They had seen, of course, how serious the situation was. There could really only be a civil war or a coup. But in the end, we were not armed for a civil war. The Right always propagated that we had weapons, but that was not true, we had no weapons. In fact, in 1972, under Allende, the Right and managed to get a new law passed in parliament that allowed them to carry out gun controls. I myself got caught up in such a control with my comrades, and navy commandos searched us. That was a clear signal for me: I saw how these forces operate.

We had achieved 36 percent in the 1970 elections. In the parliamentary election in March 1973, we received 44 percent. So, we were actually growing by leaps and bounds. The fascists couldn’t allow it to continue. In 1972, they began to try with great intensity to boycott the UP government. They then began planting bombs to spread unrest. People were beaten. The contradictions and the class struggle rapidly came to a head.”

These developments were also followed with concern in the socialist countries. “The fear that this promising path might be stifled in Chile had existed for quite some time,” Gudrun recalls.

“In March 1973, there were elections, and the Right mobilized very strongly, but the UP still managed to win a much higher percentage that Allende had won with [in 1970]. The Right realized that Allende could not be brought down through elections. They began to panic that something long-term might be setting in, and not just in politics, but also in the minds of the people. This fear was also quite palpable from afar, but no one actually expected what was to happen in September 1973, neither here nor among the Chileans themselves, because everyone clung to the idea that Chile’s army was loyal to the constitution. It was more of a hope that the army would keep a low profile in the barracks and not intervene politically. Unfortunately, that turned out to be a miscalculation.”

Nancy: The coup in Chile

“Valparaíso and Vina del Mar were occupied by commandos in the early morning hours of September 11. Navy ships had entered the port of Valparaíso and commandos had occupied streets and government buildings, universities. The U.S. fleet of Operation Unitas was stationed off the coast of Valparaíso. Unlike the coup attempt of 29 June 1973, when the people took to the streets to defend the government, this time the cities and their strategic points were taken while the people slept, so that they could not mobilize.

The navy commandos stormed the university where I was studying architecture, arrested all the students they could find, and took them in trucks to the first prisoner concentration camp in Valparaíso, Playa Ancha Stadium.

When we woke up, the marine commandos and fascist groups of Patria y Libertad were all over the street. They controlled the entrances to our building. After the broadcast of the last speech of our president Salvador Allende and the bombing of the government palace, our situation was clear – it was a matter of saving our lives. We were caught in a trap, we had to get out of our apartment and the building as quickly as possible.

But we could not get out at first. The fascists gathered in the courtyard and celebrated the coup. They blocked the exit and started drinking. Only when some other residents of the house complained did they let the residents leave. I snuck out with my husband. He was a well-known trade unionist, so we had to be extra careful. The repressive agitation was directed against trade unionists and JAP members, among others. That means we would have had no chance of survival if we had been arrested.

He went out first and I went out after him. We had agreed on certain security measures in advance. If something happened to him, I would have to go to the comrades immediately and let them know. And if I myself were to be arrested, I would have to shout so that at least others would notice. I told my comrades from the beginning: If I am arrested, you have seven hours. After seven hours, I will tell everything. I had always been afraid of torture – we knew what awaited us! We had read about the crimes of the dictatorship in Brazil…

It was not long before military communiqués on television and radio began legitimizing the military action and justifying the repression of those resisting. Starting at 3 p.m., a ‘curfew’ was imposed throughout the country. It was forbidden to go out on the streets because of the risk of being denounced, arrested, or killed by the military patrolling the streets. People were afraid. I spent the days after the coup, walking around all day, thinking. What do I do? Which way do I go now? I walked on the street and saw acquaintances from the UP, young people. I saw the fear of death in their faces.

With all the violence and military persecution in Valparaíso, a resistance action occurred on 14 September that surprised the military commandos and regiments patrolling the streets. But it did not have a major impact because the resisters did not have the necessary forces.”

Gudrun: The news of the coup in the GDR

“It was a Tuesday; the second week of studies had started for me. I turned on the radio and the news came on that the Moneda had been bombed. I remember crying and thinking, this can’t be! How can an army bomb its own government building? I mean, there were many coups before 1973 and after 1973, and the figurehead was often captured or shot, but the bombing of the seat of government was a very singular event. I spent the whole evening trying to get more detailed information and yes, we were stunned. It’s still unbelievable to me today when I think about it, about the pictures. Of course, because I knew several young communists from the Communist Youth League, I was immediately afraid. There were reports of persecution and repression. What is going on there? Have our comrades been imprisoned? Have they been shot? Tortured? And then, over the years, we came to learn of many deaths.

The GDR immediately called for solidarity actions. It was clear that the military regime would not be supported. It was not at all compatible with our ideas. Yet the official statements in West Germany were along the lines of: ‘Now our trade relations can normalize again’. For the West German government, the nationalization of the copper mines was of course an ‘encroachment on freedom’. Relatively early on, the question arose as to why the West German government, with the Social Democratic Prime Minister Willy Brandt, did not support the social democrats or the socialist Allende more. You know, this immediately revealed how economic interests trumped political considerations. The Willy Brandt’s government received advanced warning that the coup would take place and it did not warn the Socialist Allende. The GDR’s Ministry for State Security [MfS or ‘Stasi’] then intercepted this information and tried to warn Santiago, but unfortunately it was already too late.

The behaviour [of the two German states] after the putsch was also quite different. […] As we learned much later, there were concrete measures taken by the GDR to protect people and get them out of the country. Lists of the most wanted people were immediately published, and Luis Corvalán, Gladys Marín, Carlos Altamirano, and all the top officials were on it. They were mercilessly hunted down. The worst example is the artist Víctor Jara. He was so despised by the right because of the songs he wrote. There had been earlier attempts to assassinate him. At that time, he was always given protection, also by the youth association. And when they got hold of him after the coup, they tortured him in the worst way, and then murdered him.”

Flight and exile

In Nancy’s hometown, which was occupied by the navy, inhabitants were constantly checked in the streets. She recounts how people were identified as leftists and arrested based on their clothing alone. Nancy had no choice but to smile. If she went out on the street, she put on her best clothes, made herself up and smiled. That was the best, the only camouflage. She and her husband made their way to their families to say goodbye.

“On 11 September, our escape began. It lasted until the end of November. On the day of the fascist coup, we came to my in-laws’ house to say goodbye before curfew. Two days later, the police arrested my father-in-law while they were searching for my husband. He sat in detention all night, but was eventually released. My parents-in-law had fled Germany themselves decades earlier. He was a Jew from Frankfurt and had been persecuted by the Gestapo at the time. My husband had been able to secure a German passport through his parents.

In contrast to our despair, my sister-in-law and her husband were very happy about the coup. They had celebrated the events with champagne. You see, there was also this polarization within the families.

Finally, we went to my parents’ house, who were also political. Their house was also searched, and all the neighbours watched on as it happened. The situation became ever more tense for us. During curfews, neighbourhoods were cordoned off and house after house was searched. Those who had UP people in their homes could be arrested or shot.”

This situation lasted for weeks for Nancy before she hitchhiked with her husband to Santiago in November, where her party had organized an apartment for the two of them. But even there they had to flee when it became known that the comrade who had arranged the apartment for them had been arrested in Valparaíso. Nancy ended up with acquaintances through her JAP contacts, but they turned her husband away because of his prominence:

“For him, the only option was to go to the West German embassy. However, the West German ambassador, Kurt Lüdde-Neurath, refused to provide diplomatic protection. But my husband refused to leave the building. He could not be forcibly removed. Other Chileans were sent away.

Helmut Frenz, the former bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Chile and secretary general of the German section of Amnesty International, put pressure on the West German government, and the ambassador eventually had to change his position.”

In her distress, Nancy also turned to the West German Embassy and insisted on staying, since her husband was a West German citizen. The cultural attaché in charge finally relented and instructed her to appear at the ambassador’s residence that same evening, where a door would open at 9 p.m. sharp — that was her only option. Nancy agreed, and at 4 p.m., together with a comrade from her party (MAPU-OC), she drove to the ambassador’s residence in his car.

“We looked for the door but couldn’t find it. My comrade had to leave, and I walked around for four hours, always with a smile. A few minutes before 9 p.m., I met a different comrade in a small square behind the ambassador’s residence. He was to inform the party if something went wrong. The street was guarded by the military. While we were still thinking about what to do, a young man appeared and walked purposefully toward the street running along the side of the residence. I knew instinctively that I had to follow him. I said goodbye to my comrade and ran after the young man. He suddenly jumped to the side, showing me the side door. It turned out that he was a doctor and a member of the Communist Party.”

At the residence, Nancy was interrogated by the West German intelligence service, given an alien passport, and escorted to the airport because it was still possible that she would be arrested on the way. In December 1973, shortly after her husband left their homeland, Nancy was flown to West Germany. The two were taken to Hanau in “a refugee shelter where Russians and former GDR residents were also housed. Each family, no matter how large, had only one room, there was one toilet for everyone, for washing up only one sink, nothing else.”

Nancy and her husband left for Cuba, from where they actually wanted to go to Argentina, but there too a military coup struck. In 1976 they were supposed to return to the FRG “and I said, no, that is out of the question for me.” Instead, the MAPU-OC arranged for her to go to the GDR.

Arrival in the GDR

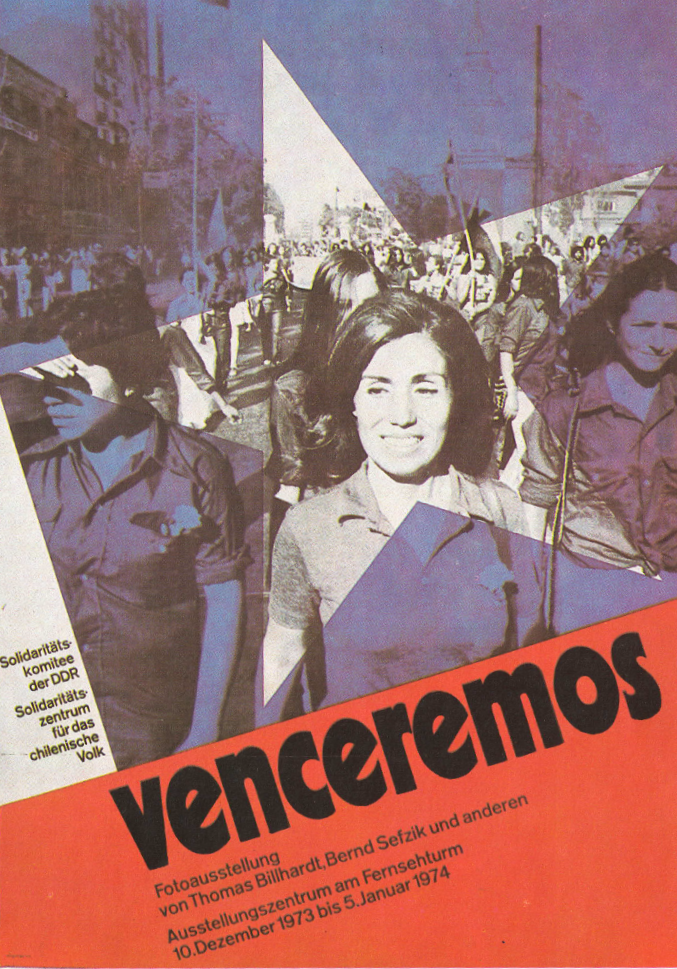

Immediately after the coup, the GDR became the main host country for Chilean exiles in Eastern Europe. It directly took in about 2,000 refugees and provided them with an interest-free loan and new apartments. A further 3,000 Chileans would follow over the next 15 years. Gudrun recalls: “Relatively quickly, concrete measures were implemented. The refugees – we called them emigrants at that time – were not only distributed to Berlin, but to different cities. […] It was clear from the start that they would not only be taken in and left to their own devices, but they would be given apartments, which was not so easy in the GDR at that time either, because we still had a big housing problem. Fortunately, the housing program had already begun, so the Chilean emigrants actually always received appropriate housing. Also, school and education, jobs and places to study, so that many were able to continue their education relatively seamlessly — despite the language barrier, of course. The same was true for their professions, which they then either completed here first or were able to work straight away.”

Nancy also completed her studies in the GDR, earned her doctorate and worked there. The country quickly became a new home for her:

“In the GDR I had received many things that I had never had before — neither in Chile nor in the FRG. I had everything I needed to develop freely. In Magdeburg, a new apartment block was provided for us Chileans. We received 5,000 GDR Mark per head. That was a lot of money back then. With that we were able to buy all the household appliances, furniture and bedding we needed. I had never had my apartment carpeted before! Everything was new. We had to pay rent every month, of course, but it was relatively small. We paid 50 GDR marks for three rooms. Through work, I earned 660 marks alone, and then my husband’s wages came on top of that.”

German classes were organized for the Chileans in the early morning hours from 7 to 9 a.m. so that they could learn before going to work or university. Since Nancy joined later and the teacher was no longer teaching due to illness, she began working at the Wohnungsbaukombinat (housing construction enterprise) Magdeburg without knowing the language. There she joined a work brigade:

“The brigade would meet every week to discuss completed and upcoming work. I worked with architects, graduates from Weimar, who were redesigning the city center of Magdeburg. We worked in a comradely atmosphere, our office was the craziest of all, of course, with so many architects.

Living in the GDR shaped me and strengthened my communist convictions. The laws also impressed me: as a woman, I had just as many rights as the men. I had never experienced that before. In the Wohnungsbaukombinat in Magdeburg or in the construction company in Jena, there were extra rooms just for women where they could rest if they felt uncomfortable. There was also one day of paid housework per month. Of course, this was all a process; women were still doing too much housework in addition to their professional work. But it was going in the right direction. My time in the GDR was very good.

At that time, I also saw how the West’s propaganda against the GDR was becoming more and more intense. It was aimed at arousing envy for luxury goods in the West: clothes or tropical fruits and so on.”

The exiled members of the various UP parties continued their political struggle from abroad. In the GDR, “the structures of the Unidad Popular […] were able to re-establish themselves in a certain way, thanks to the commitment of the Chile Antifascista office,” Gudrun explains.

“This office emerged from the Chilean Embassy in the GDR, and became the hub for solidarity actions in the different countries and for maintaining contacts with our political organizations. The Communist Party of Chile had its headquarters in Moscow, while the Socialist Party had its headquarters here in the GDR. The fact that […] the general secretary of the Socialist Party, Carlos Altamirano, was smuggled out of Chile in the trunk of the car of a GDR intelligence agent certainly played a role there. Altamirano then found asylum in the GDR for a long time. After the coup, the GDR severed diplomatic relations with Chile. Only a trade mission was maintained in Chile, which was used to get more people out.”

In the International Federation of Teachers’ Unions (FISE), which had its headquarters in Berlin in the 1980s, Gudrun worked with Chilean colleagues to provide information about the situation in Chile and to support comrades:

“I didn’t just do the job by the book; I was particularly committed to the Chilean cause. […] I had kept in touch with the different Chilean teachers’ unions and looked after people when they were here. We had also been in contact with Radio Moscow from time to time to read out appeals and so on. I was then given an ‘Honorary Certificate for Chile Solidarity from the Chile Antifascista Office’.”

“The solidarity was massive,” Nancy recalls. “There were many events about Chile, and we were very privileged. They gave us everything. To this day, that experience touches me.” West Germany eventually accepted members of various UP parties, albeit reluctantly, as Nancy points out, “In the West, the whole Christian Democratic party [CDU] was against the Chileans. We were called terrorists. They only accepted political emigrants from Chile where the Social Democrats were in government — in Hamburg, Frankfurt, West Berlin, Hanover, and so on.”

After 1990

In 1988, Nancy made an attempt to return to Chile and start again. For almost two years she tries to gain a foothold in her old homeland, but the poor conditions make the project impossible. She had to wait two years to get her academic degree recognized and was unable to earn any money in the meantime. So, she returned to the GDR, but the society she had gotten to know was falling apart:

“Then came our great defeat. I came back and suddenly found myself back in capitalism! Everything was gone and I had to start from scratch again. I was in Berlin and had no political home. MAPU was Marxist-Leninist, but the members were mostly petty-bourgeois – lawyers and academics – there were few workers and peasants in the end. Then in 1996 I joined the Communist Party of Chile here in Germany. After our defeat, that was the only party that expressed my ideals. The Chileans in the GDR were afraid because there was a danger that the West German government could extradite us. So, they formed an association to protect us.”

In Chile itself, the dictatorship continues to have an impact decades later. Gudrun and her husband have been traveling to the country regularly since 1990. They quickly noticed how the stigmatization of the socialist project continued even after the end of the dictatorship. From their travels in the 1990s, Gudrun reports on the whispers of left-wing activists, the silence of those responsible, the absence of the UP period in history books and Allende in the public sphere:

“We visited friends, all people I had met through FISE. People who had never left Chile, and people who had had to emigrate and then had returned. It was very interesting to see, because in 1995 the dictatorship was still very present even among these people themselves. We always introduced ourselves as former GDR citizens and had very different reactions: Some said nothing at all, others remarked that we had immediately helped — but then they would also speak more quietly. That was really striking. We were with acquaintances in the Ministry of Education and had to realize that there, too, history is written by the victor, of course, and the Unidad Popular either did not appear in the textbooks at all or was negatively charged. We also saw a monument where all Chilean presidents since independence in 1818 were listed, only in 1970 there was no president, the last one was Eduardo Frei and then Pinochet was mentioned. Allende didn’t appear at all and that was remarkable to us.”

When the couple picked up two hitchhikers on their journey and Gudrun had to explain that she had practiced her Spanish with Chilean emigrants, they were met with incomprehension. Emigrants were those who had escaped the time when there was “nothing, nothing to eat, no work.” Gudrun encountered a completely distanced and distorted image of that time among young people there:

“They had heard, if they heard anything at school, only negative things. That people had been lifted out of poverty, that there were people who could move into a permanent house for the first time; that land occupations no longer had to take place to make a shelter out of cardboard and wood; that there was a half-litre of milk for the children; that there was a school lunch; that the children could go to school at all – none of that was taught.”

Forebodingly, Gudrun recognized in this a parallel to how the GDR would also to be dealt with:

“That was actually the harbinger of what is now taking place here with us: That the GDR is essentially denigrated, and even positive achievements are somehow given a negative touch. That was frightening. What we witnessed back then almost 30 years ago, was now repeating here.”

Despite all the difficulties in Latin America, Nancy sees the legacy of the UP continuing in the struggles of the left-wing forces on the continent:

“Allende’s program provided that each child would receive half a litre of milk. Enough food for all. Education for all. […] And you see the revival of these goals in the progressive governments of Latin America: Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and so on. They also tried to bring about social justice through the existing laws. But this is incredibly difficult. In 2000, it started with Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. As an army officer, he had the military behind him. Now there’s also an attempt in Colombia, but that’s still in the stars. That’s the problem with these progressive governments in Latin America: the popular majority often manages to win the executive (the presidency), but not the parliament, the judiciary, and even less so the military. Venezuela remains the exception in this regard.”

This makes it all the more important for her to learn from the experiences of the UP period and to stand in solidarity:

“Because they were not well prepared for the coup at that time, many comrades of the Communist Party in Chile fell. They had not assessed the situation well. They tried to stop fear from spreading. But in the end, we all protected each other – otherwise I wouldn’t be here today either.”