How the DDR came to provide military support for the Mozambican liberation struggle

Mascha Neumann

25 April 2024

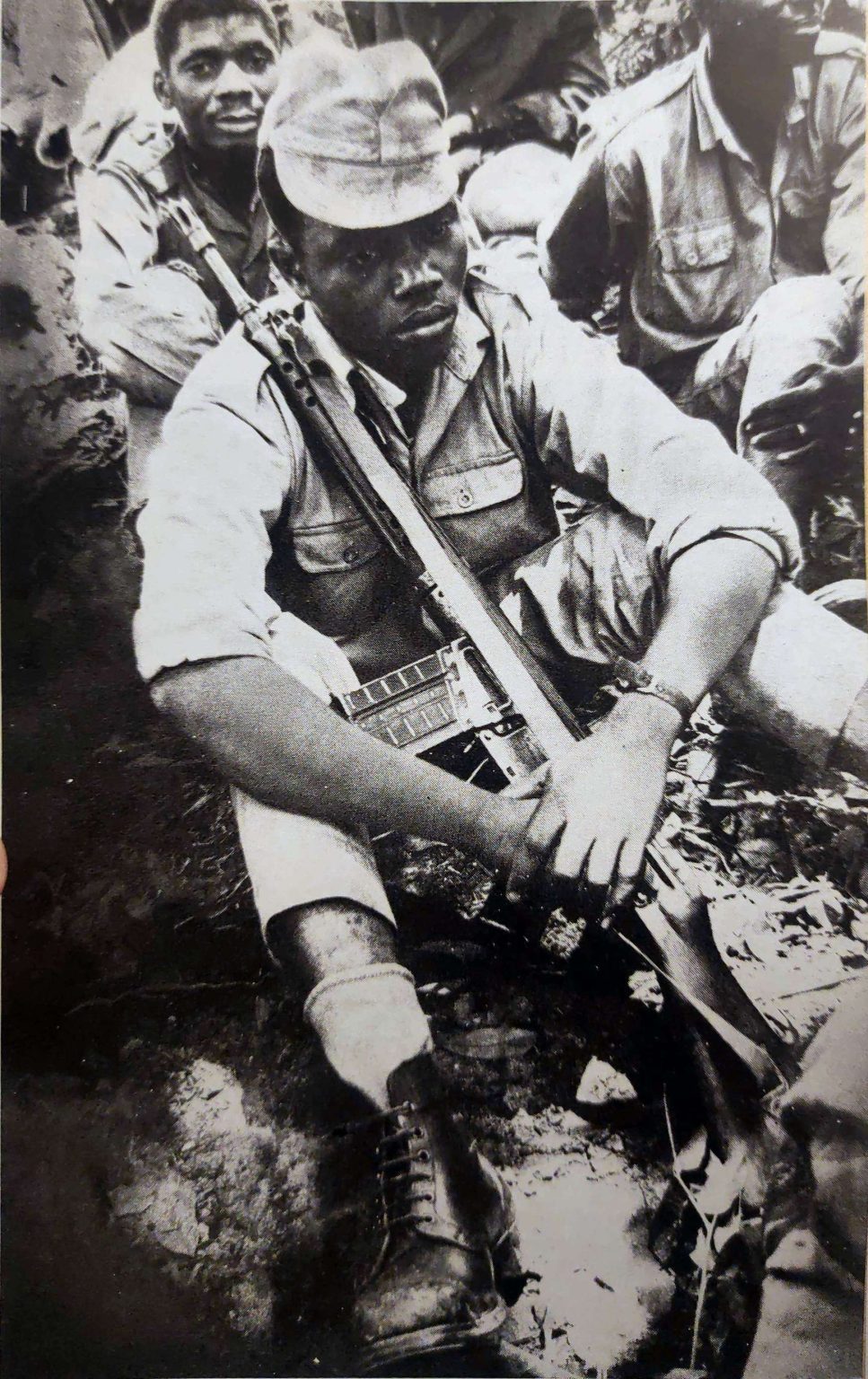

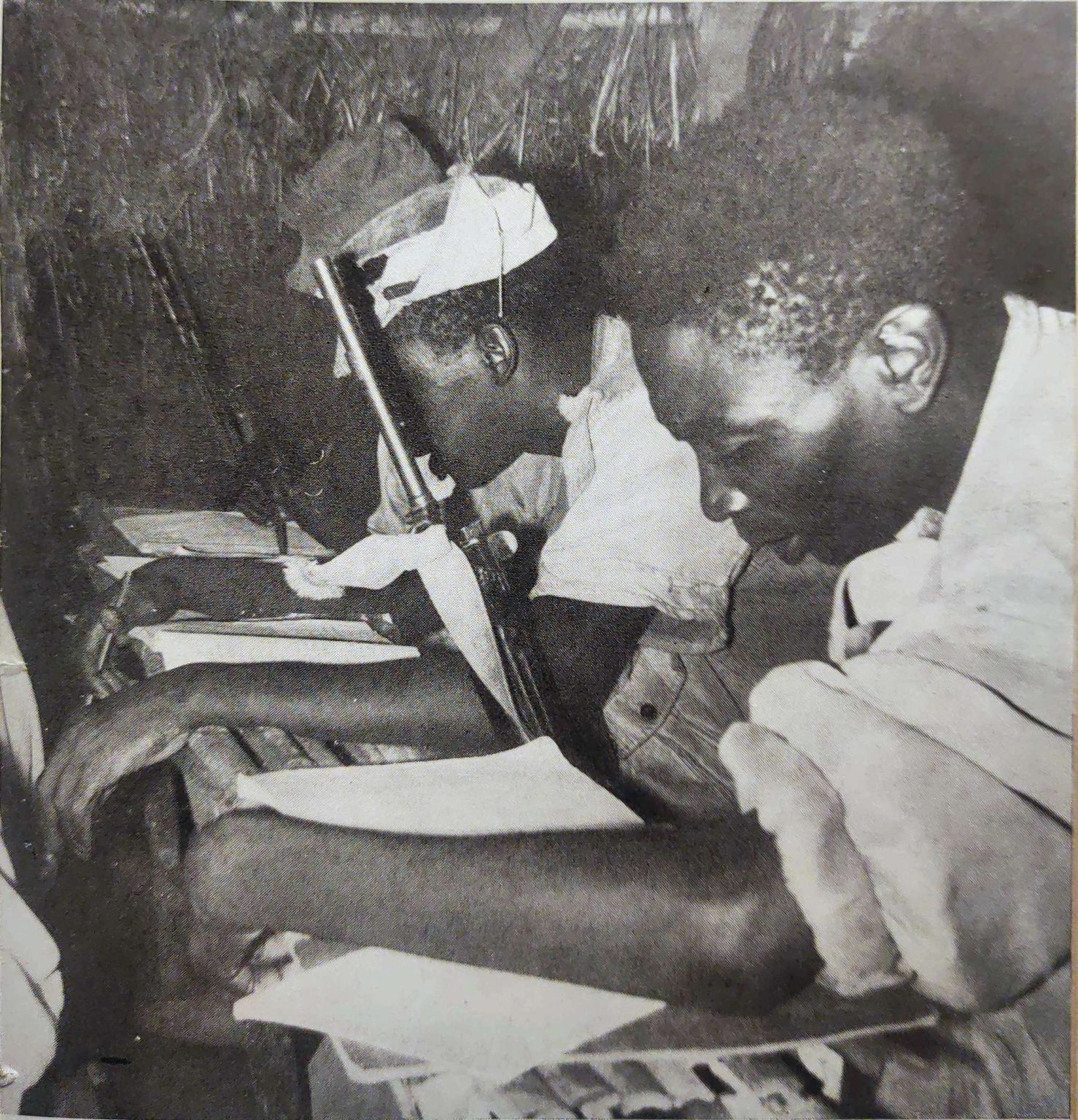

Today, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) is remembered by many progressive forces around the world as a pioneer in support for the national liberation movements of the 20th century. The GDR’s anti-imperialist solidarity ranged from education programmes, medical care, industrial and agricultural development, civilian aid, financial support, the printing of agitation material, and military training and equipment. In retrospect, this military support seems like a logical extension of international solidarity. However, at the beginning of the 1960s, it was quite controversial in the GDR whether the delivery of East German weapons and ammunition to organisations such as the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) was appropriate.

In principle, the use of weapons in the fight against colonial rule was considered legitimate in the socialist camp. However, the former diplomat Helmut Matthes1Matthes was GDR ambassador to Tanzania (1973–76) and Mozambique (1983–88). He also worked for several years as a university lecturer at the Institute for International Relations at the Academy for State and Law in Potsdam. describes the GDR’s relationship to armed struggle as ambivalent. From the outset, “political and diplomatic means were regarded as decisive”.2Matthias Voß, Die Beziehungen der DDR – VR Mosambik zwischen Erwartungen und Wirklichkeit. Helmut Matthes über Stellung und Praxis der Beziehungen zu Mosambik im Rahmen der Afrikapolitik der DDR, in: Matthias Voß (Hg.), Wir haben Spuren hinterlassen! Die DDR in Mosambik. Erlebnisse, Erfahrungen und Erkenntnisse aus drei Jahrzehnten, Münster 2005, pg. 12–33, here pg. 13. In the nuclear age, especially after the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the states allied with the Soviet Union were concerned that the confrontation with the imperialist states could escalate into mutual annihilation. Against this background, the concept of peaceful coexistence (“the peaceful coexistence and co-operation between states of different social orders in the era of transition from capitalism to socialism”) became a guiding principle of Soviet foreign policy, while other socialist states such as the People’s Republic of China and Cuba took a much more offensive approach to the question of armed anti-imperialist struggle.3In the GDR literature from the 1980s, the policy of peaceful coexistence for the colonies was also explicitly rejected: “It is not possible to apply the principles of peaceful coexistence to the class struggle within the capitalist states or to the anti-colonial struggle or to the ideological class struggle because these spheres constitute wholly different forms of social relations. Peaceful coexistence thus does not equate to settling for the social status quo.” Dictionary of Scientific Communism, Berlin 1982, pg. 109.

A closer look at the development of the GDR’s position towards the armed struggle in southern Africa reveals an initial hesitancy that can be attributed to several factors: Could another nuclear crisis unfold across Africa after Cuba? Had legal and diplomatic efforts really been exhausted? Should East German weapons be exported for conflicts abroad, even if they might come up against West German weapons? Was it possible to ensure that the guns ended up in the right hands? Could the GDR industry keep up with the demand of the liberation struggles in both East Asia and Africa? In view of intensifying hostilities in southern Africa in the mid-1960s and the escalation of the Sino-Soviet split, the political leadership in Berlin decided in early 1967 to commit itself to providing military support to the liberation movements in Africa. Thus, the GDR began to spend millions of marks on military aid and training programmes for fighters from national liberation movements and former colonies.4Exact figures for the entire period are difficult to determine, but for the 10-year period from 1973 to 1983 alone, the Ministry of Defence spent around 700 million marks on military support for the former colonies and liberation movements. Cf. Hans-Georg Schleicher/Ilona Schleicher, Waffen für den Süden Afrikas. Die DDR und der bewaffnete Befreiungskampf, in: Ulrich van der Heyden/Ilona Schleicher/Hans-Georg Schleicher, Engagiert für Afrika. Die DDR und Afrika II, Münster/Hamburg 1994, pg. 7–30. Contrary to the narrative propagated by the West German press (“Honecker’s Africa Corps”), the decision to supply “non-civilian goods” was only taken after careful consideration.

The socialist camp and the fight against the Portuguese colonial regime

The initial reluctance in the GDR with regard to the plans of the Mozambican liberation front FRELIMO, which wanted to emulate the liberation movements in Angola (1961) and Guinea-Bissau (1963, then still “Portuguese Guinea”) and take up the armed struggle against the colonial power Portugal, illustrates the ambivalence mentioned by Matthes. After a visit by two FRELIMO representatives to the GDR in 1963, the subsequent report of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MfAA) stated that the liberation front currently saw no other way of achieving independence for Mozambique. Although this was met with a certain degree of understanding, it was criticised at the same time:

“FRELIMO pays too little attention to the questions of the simultaneous utilisation of legal possibilities of the struggle in order to create an even broader national front against Portuguese colonialism (e.g., attempts to create a legal opposition, contacts with other parties and with the so-called assimilados5The “assimilados” were a legally defined group of people in the Portuguese colonial system. These were inhabitants of the colonies from the local population who were granted citizenship rights based on the fulfilment of certain requirements (knowledge of Portuguese, Western lifestyle, employee status or landowner), which made them appear sufficiently “civilised” in the eyes of the colonial administration. However, the majority of the local population (over 99% in the 1950s) were not recognised as citizens and therefore had fewer rights and received, for example, lower wages, even for the same work. See Marvin Harris, The Assimilado System in Portuguese Mozambique, in: Africa Special Report, 3 (1958), pg. 7–10, URL: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/assimilado-system-portuguese-mozambique/docview/1304046356/se‑2. in the administration, participation as individual candidates in elections, etc.).“6Jeschewski (4. AEA), Information/Aufenthaltsbericht, 27.01.1964, in: PA AA M 1‑A/17423, pg. 48–52.

A “Chinese influence” was suspected behind this “one-sided orientation towards the armed struggle” — not least due to the recent visit of one of the FRELIMO representatives (Marcelino dos Santos, who later became Vice President of the Liberation Front) to the People’s Republic of China, where he was said to have been personally received by Mao.7Both quotes ibid. The quote also indicates that the decision to join the armed struggle was considered premature and that it was considered more promising to first secure the support of other Mozambican actors.

The fact that the Soviet Union finally decided to support FRELIMO militarily in 1964 despite its own reservations (initially by offering to train 40 fighters in the USSR) is said to have been seen by its chairman, Eduardo Mondlane, as an attempt to deter China from interfering too much in Mozambique.8Natalia Telepneva, Mediators of Liberation: Eastern-Bloc Officials, Mozambican Diplomacy and the Origins of Soviet Support for Frelimo, 1958–1965, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 43 (2017) 1, pg. 67–81, here pg. 79. The Soviet decision will not have been insignificant for their allies either. When FRELIMO increased its efforts to obtain military support from the socialist states after the start of hostilities in September 1964, it was quite successful: Bulgaria and the ČSSR, among others, agreed to supply weapons in the spring and summer of 1965.9ibid. Weapons had also been requested from the GDR since 1965 at the latest, and FRELIMO was not alone: the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) from Angola and the ZAPU from Rhodesia10The former British colony was ruled by a white minority government from 1965 to 1980. The country has been called Zimbabwe since 1980. ZAPU stands for Zimbabwe African People’s Union., which borders Mozambique, had also repeatedly made such requests.11Klaus Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität. Militärbeziehungen und Militärhilfen der DDR in die „Dritte Welt“, Berlin 2012, pg. 108. However, the GDR was not yet able to agree to arms deliveries at this time.

The fact that the Soviet Union finally decided to support FRELIMO militarily in 1964 despite its own reservations (initially by offering to train 40 fighters in the USSR) is said to have been seen by its chairman, Eduardo Mondlane, as an attempt to deter China from interfering too much in Mozambique.8Natalia Telepneva, Mediators of Liberation: Eastern-Bloc Officials, Mozambican Diplomacy and the Origins of Soviet Support for Frelimo, 1958–1965, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 43 (2017) 1, pg. 67–81, here pg. 79. The Soviet decision will not have been insignificant for their allies either. When FRELIMO increased its efforts to obtain military support from the socialist states after the start of hostilities in September 1964, it was quite successful: Bulgaria and the ČSSR, among others, agreed to supply weapons in the spring and summer of 1965.9ibid. Weapons had also been requested from the GDR since 1965 at the latest, and FRELIMO was not alone: the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) from Angola and the ZAPU from Rhodesia10The former British colony was ruled by a white minority government from 1965 to 1980. The country has been called Zimbabwe since 1980. ZAPU stands for Zimbabwe African People’s Union., which borders Mozambique, had also repeatedly made such requests.11Klaus Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität. Militärbeziehungen und Militärhilfen der DDR in die „Dritte Welt“, Berlin 2012, pg. 108. However, the GDR was not yet able to agree to arms deliveries at this time.

West Germany’s military and political support for fascist Portugal

However, in the case of the GDR, the question of arms deliveries, especially for the Portuguese colonies, was also much more sensitive than for the other socialist countries: after all, weapons from both German states would be involved in direct confrontation there. At the beginning of the 1960s, the Portuguese leadership turned to its NATO allies for help. The government under dictator Salazar claimed to be threatened by a communist uprising supported by the Soviet Union in its so-called “overseas provinces“12In 1951, Portugal redefined its colonies as “overseas provinces” by amending its constitution and from then on officially regarded them as an integral part of the country. This went so far that the Portuguese government claimed after its accession to the UN (1955) that it did not administer any dependent territories. See United Nations, A Principle in Torment. 2, The United Nations and Portuguese administered territories / Office of Public Information, New York 1970.. As a result, a number of states supported fascist Portugal with loans, fighter planes, warships, ammunition, and chemical defoliants, among other things.13Elizabeth Schmidt, Africa, in: Richard H. Immerman/Petra Goedde (Hg.), The Oxford Handbook of the Cold War, Oxford 2013, pg. 265–285, here pg. 276. Up to this point, the USA had been Portugal’s biggest financial and military supporter, partly in order to secure its strategically important military bases in the Azores and Cape Verde.

Although the loans granted were intended for use in Portugal, this freed up funds elsewhere that could be used for the administration of the colonies and ultimately also for the colonial wars.14Thomas H. Henriksen, Revolution and Counterrevolution. Mozambique’s War of Independence, 1964–1974, Westport/London 1983, pg. 173. Following the adoption of the “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples” by the UN General Assembly in December 196015The resolution was adopted with 89 votes in favour and none against. Only 9 states abstained, including Portugal, South Africa, Great Britain, France and the USA. See Wilfried Skupnik, Portugals Kolonialismus und die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Schluss), in: Vereinte Nationen, German Review on the United Nations, 22 (1974) 4, pp. 113–118, here pg. 114. on the initiative of the Soviet Union16Franz Ansprenger et al. (Hg.), Wiriyamu. Eine Dokumentation zum Krieg in Mozambique, München 1974, pg. 4. and in view of the worsening situation in the Portuguese colonies, the USA under its new President John F. Kennedy significantly restricted the supply of arms to Portugal. The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), which as a non-member did not have to justify itself to the UN, subsequently replaced the USA as the main supplier of military equipment.17Luís Nuno Rodrigues, The International Dimensions of Portuguese Colonial Crisis, in: Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo/António Costa Pinto, The Ends of European Colonial Empires: Cases and Comparisons, London 2015, pp. 243–267, here pp. 257 ff. West Germany, in turn, was overtaken in this respect in the first half of the 1970s by France, which was not a NATO member at the time and did not impose any restrictions on the deployment locations of the weapons supplied, etc. Cf. Henriksen, Revolution and Counterrevolution, pg. 175.

The Federal Republic made a significant contribution to the Portuguese colonial wars on a military, economic, and political level.18In addition to the publications by Schroers, Henriksen, Lopes and Rodrigues on this topic, the most recent German-language publication to be mentioned is Nils Schliehe, Deutsche Hilfe für Portugals Kolonialkrieg in Afrika. The Federal Republic of Germany and the Angolan War of Liberation 1961–1974, Munich 2016. In the 1960s, large quantities of surplus Bundeswehr material went to Portugal, including mainly weapons and military aircraft. In addition, the Portuguese military was supplied with new products by West German industry until the 1970s, including warships and all-terrain vehicles, which were also used in the colonies.19Thomas Schroers, Die Außenpolitik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Die Entwicklung der Beziehungen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zur Portugiesischen Republik (1949–1976), Dissertation (Universität der Bundeswehr Hamburg), Hamburg 1998, pg. 60; Rui Lopes, West Germany and the Portuguese Dictatorship, 1968–1974. Between Cold War and Colonialism, Basingstoke/New York 2014, pg. 145. In 1965, a so-called “end-use clause” was negotiated to exclude transfer and thus use in the colonial wars. However, it was known that weapons and other military material and equipment supplied by the Federal Republic were still being used there.20Schroers, Die Außenpolitik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, p. 72 ff. For a well-known case in which the omission of the final destination clause was even mutually agreed, see Lopes, West Germany and the Portuguese Dictatorship, p. 147. This involved three military ships whose purpose was obviously to be used in the colonies. Although Bonn repeatedly delayed the delivery, all three were ultimately handed over to the Portuguese army and used in the colonial wars (cf. ibid.). See also FRELIMO reporting: FRELIMO, West Germany involved in the Portuguese Colonial War, in: Mozambican Revolution No. 1, December 1963, pg. 3–5, URL: https://jstor.org/stable/al.sff.document.numr196312 Portugal’s repression of the liberation movement in Mozambique became increasingly brutal, culminating in the massacre of Wiriyamu in 1973, in which 400 villagers were gunned down by the Portuguese army and security services.21Ansprenger et al. (Hg.), Wiriyamu.

The turning point for the GDR and the beginning of the “delivery of non-civilian goods”

Another indication that there was great fear of an escalation was the handling of a draft proposal by GDR Foreign Minister Otto Winzer from the spring of 1965, which advocated for a definitive decision to support liberation struggles with military material. The reason provided was explicitly the repeated requests from various liberation movements, some of which the GDR’s Solidarity Committee was already supporting with civilian and even paramilitary goods — including the Angolan MPLA and the Mozambican FRELIMO. This document was classified as so confidential that it was not initially discussed with any other government agency. Since it was ultimately not submitted to the Politburo of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) for approval, it is reasonable to assume that at least one of the three ministers (including the Minister of National Defence, Heinz Hoffmann, the head of the Ministry of State Security, Erich Mielke, and the Minister of the Interior, Friedrich Dickel) to whom the draft was submitted in advance, applied the brakes.22Storkmann, Geheime Waffen, pg. 108.

However, the issue was not off the table. After Erich Honecker had spoken out against the arming of such groups in November 1966 (in his function as Central Committee Secretary for Security Affairs at the time)23ibid., pg. 109., the Politburo finally reached a definitive decision on 10 January 1967 and approved the possibility of “supplying non-civilian goods to national liberation movements in Africa”.24Politbüro (ZK der SED), Arbeitsprotokoll Nr. 1, TOP 14, 10.01.1967, in: BArch DY 30/45305. According to Matthes, the basis for this policy shift was the intensification of political contacts at international events during the 1960s and the visits of high-ranking representatives of the liberation movements to the GDR.25Voß, Die Beziehungen der DDR – VR Mosambik, pg. 12. It stands to reason that more frequent encounters enabled better familiarisation and thus contributed to the decision. For example, FRELIMO President Mondlane had visited East Berlin in person for the second time just six weeks before the decision. Whether the Soviet Union had also urged the SED to reconsider its previous hesitation and follow their example has not yet been clarified, as there are no meaningful sources on this.26Storkmann also comes to this conclusion. See Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität, pg. 109.

What certainly also contributed to this decision was the intensification of fighting by many liberation movements in southern Africa in the mid-1960s. By 1966 (at the latest), military activities had become a defining factor in the liberation struggle. It is also interesting to note that a Cuban military delegation visited the GDR at the end of 1966, whose influence on the decision in favour of arms deliveries cannot be ruled out, although it cannot be clearly proven. However, since the talks dealt with topics relating to the armed liberation struggle and, among other things, specifically with the question of whether the GDR could provide weapons and military training, this is another probable influence in favour of the decision.27Schleicher/Schleicher, Waffen für den Süden Afrikas, pg. 12.

This decision was then immediately followed by the first concrete deliveries. FRELIMO was prioritised and received the largest number of weapons and ammunition. The reasons for the MfAA’s draft decision stated that the liberation movements in question were the most important, most successful, and most progressive forces in the respective colonies and that the military aid was in line with the foreign policy principle of supporting national liberation.28Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität, pg. 246. In this way, the GDR had not only joined its socialist allies (and China) in its stance on armed struggle, but also followed other countries on the African continent that could look back on a successful liberation struggle. Algeria, for example, which had been independent since 1962, had gained extensive combat experience in its war of liberation against France and, at the request of the FRELIMO leadership, had provided military training and equipment for its first 250 fighters.29Helen Kitchen, Conversation with Eduardo Mondlane, in: Africa Report, 01.11.1967, S. 31–51, here pg. 52.

Active diplomacy of the liberation movements — the example of FRELIMO

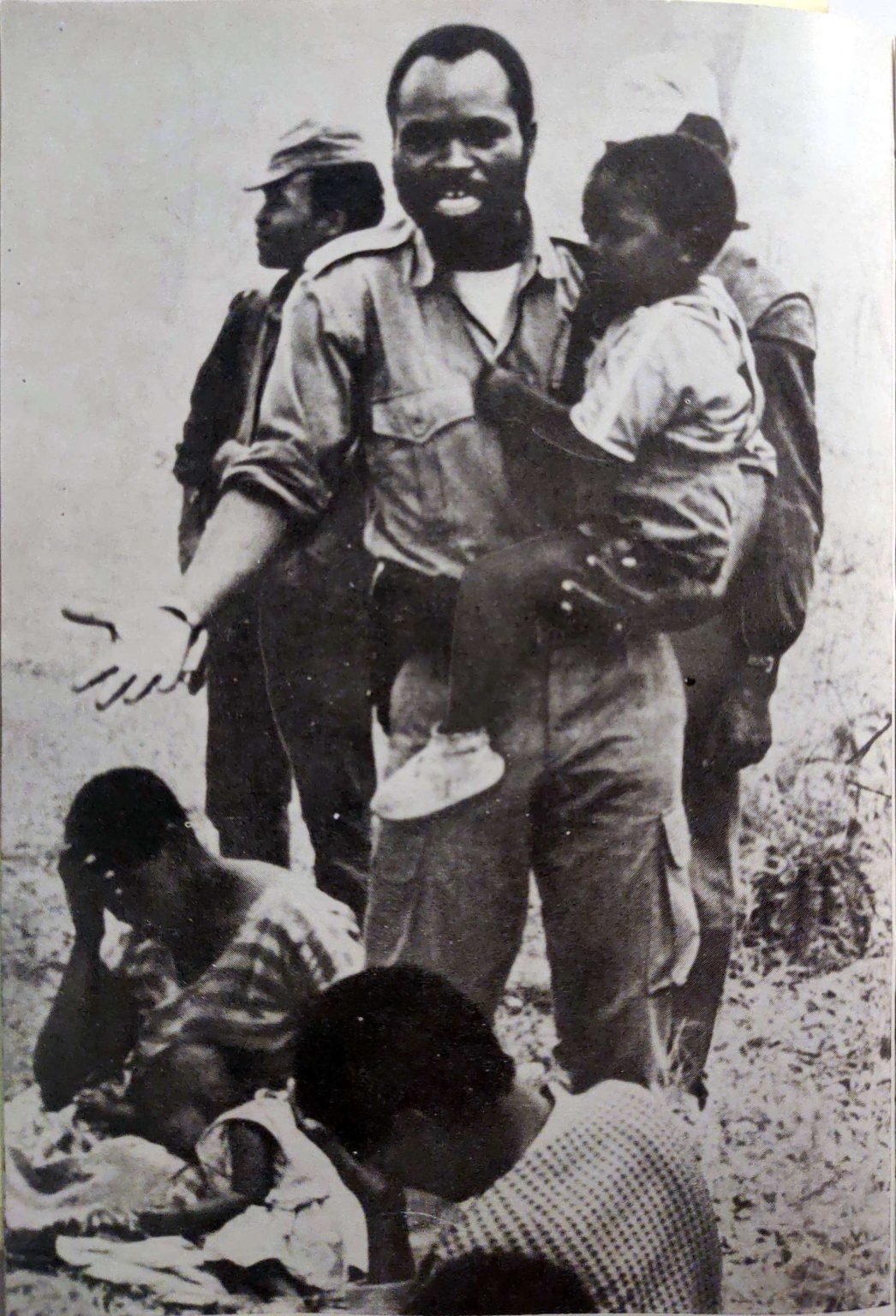

Since 1967, arms deliveries from the GDR to FRELIMO have taken place almost every year.30Storkmann, Fighting the Cold War in southern Africa?, pg. 156. Their volume, like the overall support, increased significantly in the early 1970s. This can be explained in part by the uncertainty that had previously prevailed, triggered by Mondlane’s assassination in 196931Mondlane was murdered on 3 February 1969 in a letter bomb attack by the Portuguese secret police PIDE, which was active both in Portugal and internationally. and the subsequent power struggles within the liberation front. Support in other areas was maintained during this difficult period and even increased in some areas.32This applied in particular to support in the education sector, including the deployment of teachers. However, supplying weapons on a large scale to an organization in the midst of an ideological reorientation would have represented a risk. During his leadership of FRELIMO, Mondlane had increasingly moved towards the socialist states and eventually turned his back on the West definitively.33Victoria Brittain, They had to die: assassination against liberation, in: Race & Class, 48 (2006) 1, S. 60–74, here pg. 64. Yet following his assassination, it was unclear who would succeed him in the ideologically very heterogeneous Liberation Front. In May 1970, FRELIMO’s central committee finally appointed army chief Samora Machel as the new president. This meant that the wing around Marcelino dos Santos, who had long been regarded as socialist and subsequently became vice president, had finally prevailed.34George Roberts, The assassination of Eduardo Mondlane: FRELIMO, Tanzania and the politics of exile in Dar es Salaam, in: Cold War History, 17 (2017) 1, pg. 1–19, here pg. 17.

In the run-up to the first official reception of a FRELIMO delegation by the GDR government (not by the Solidarity Committee as had previously occurred), which took place in April 1972, the Central Committee of the SED planned the delivery of a large consignment of infantry weapons and corresponding ammunition without any concrete requests from FRELIMO, in order to be able to respond immediately to possible enquiries during the visit.35Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität, pg. 248. This rather unusual approach was due to the fact that there were acute fears of the Liberation Front moving closer to China. A delegation led by Machel in his new role as FRELIMO president had visited China, North Korea and Vietnam in autumn 1971, which was apparently perceived as so worrying that the GDR Consulate General in Tanzania subsequently invited him to a “meeting”. There, Machel said he very pleased with his trip, during which China had emphasised its willingness to provide extensive material support and further arms deliveries. He praised the way in which the delegation had been received in all three Asian countries. For him, this clearly represented a criterion for the attitude towards the liberation movement and he drew comparisons with other socialist states, which came off badly. He noted that the “SU, as the first and strongest socialist country […] apparently showed little interest in the FRELIMO problems”.36Zenker (GK Daressalam), Aktennotiz/Gesprächsvermerk, 12.10.1971, in: PA AA M 1‑C/6071, pg. 1.

According to the consulate’s report, Machel also described the support from the GDR as being in need of improvement. Although the FRELIMO president showed understanding for the economic difficulties of the socialist countries, he nevertheless openly criticised them. Numerous wishes had been formulated towards the GDR, but there was a lack of realisation of the promises made: verbal assurances were of no use. It was much more important to achieve an improvement in material aid from all socialist countries. Machel’s clear words show that FRELIMO still did not want to be drawn into the Sino-Soviet conflict: Help was explicitly accepted and also expected from all socialist states. At the same time, the dispute in the socialist camp had the potential to gain more support overall. The sources cited here suggest that FRELIMO sought to encourage the Soviet-aligned states to “outbid” China’s pledges of support.

In the GDR, this criticism was taken to heart. During Machel’s visit in April 1972, it was explained to him that the GDR’s options were severely limited due to its obligations towards Vietnam. In this context, reference was also made to the necessary coordination within the framework of the Warsaw Treaty and to the Potsdam Agreement, which only permitted the production of weapons in the GDR to a limited extent. Nevertheless, the government was prepared to continue supporting FRELIMO and to fulfil its wishes if these were communicated at an early stage. From then on, regular lists of possible deliveries were drawn up, partly in response to specific demands and partly in anticipation of further requests.37Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität, pg. 249.

Support in the “non-civilian” sector did not end even when Mozambique’s independence became foreseeable as a result of negotiations with Portugal following the Carnation Revolution (1974). On the contrary, the GDR was convinced that the political changes in Portugal and the resulting new situation in the Portuguese colonies even required “increased support for the anti-imperialist struggle of these peoples“38Sekretariat (ZK der SED), Arbeitsprotokoll Nr. 109, 14.10.1974, in: BArch DY 30–62668, pg. 73., which was reflected not least in an additional consignment of a considerable amount of “non-civilian” material, which was decided by the SED Politburo in October 1974. During the second official FRELIMO delegation visit to the GDR (December 1974) and beyond, further extensive (partly paramilitary) deliveries were requested by Machel and authorised in Berlin.39Storkmann, Geheime Solidarität, pg. 250. It is obvious that FRELIMO’s position within Mozambique was to be strengthened militarily before its official “release” into independence in order to secure its power in the long term.

Conclusion

Portuguese fascism was overthrown in the Carnation Revolution in April 1974. The following year, the last Portuguese colonies in Africa secured their independence. The liberation movements in Mozambique, Angola, and the other colonial territories played a central role in overthrowing the fascist dictatorship. Through their fighting, they massively overstretched the Portuguese military and the state budget, thus creating a revolutionary situation in the metropolis, which progressive officers and political organisations were then able to successfully control.

Portugal, a founding member of NATO, was supplied with armaments by its allies (including West German rifles and warships) before and during the colonial wars. This gave the Salazar regime – which was not willing to cede its so-called “overseas territories” peacefully – a great initial military advantage over those campaigning for independence in the colonies. Subsequently, the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), the MPLA, and finally FRELIMO had no other way out of the oppression than to declare armed war on the coloniser, despite the unequal balance of power. The socialist states recognised this fact and began to support the anti-colonial liberation struggle with weapons and military training in the mid-1960s. This was not a straightforward process; in the GDR in particular, there were a number of considerations that led to caution and restraint in military support until 1967 (and partly beyond). Over time, however, political confidence grew and, thanks to closer relations with the liberation movements, the supply of “non-civilian” assistance was secured.

The effects of the Sino-Soviet split were also clearly felt in the Portuguese colonies. While the Mozambican liberation front FRELIMO, for example, was able to exploit the rivalry to exert pressure on the socialist states and demand more support from all sides, the split undoubtedly undermined the unity of the anti-imperialist struggle and even encouraged bloody clashes between different liberation movements within some countries, as was particularly evident in Angola.

With regard to the Carnation Revolution, it should not be underestimated that East German weapons and non-military support for the liberation struggles in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea-Bissau not only had an impact in Africa, but also influenced significant developments in Europe. Socialist solidarity thus made an important contribution to the weakening of Portuguese colonialism and the overthrow of Portuguese fascism.