An easy question, though hard to answer

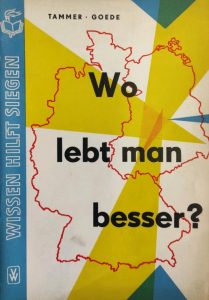

Ladies and gentlemen, of course I am sitting before you as a lucky man. For not only am I allowed to publicly expound here and in front of you, I can also do so on the best and simplest topic of the evening: Was the GDR the better Germany?

Nothing could be easier than answering this question. Let’s look at the balance sheet of the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. The GDR had relegated the USA to third place in the medal haul, and in the country comparison it ranked second behind the Soviet Union. Thus, in comparison with the Olympic team of the Federal Republic, it was undoubtedly the better Germany. What this meant is also apparent in comparison with the most recent Olympic Games in Tokyo: the all-German team was “far from it”. Since the end of the GDR, competitive sports have gone downhill, as have popular sports. The compulsory subject of sport, which had been part of every direct course of study in the GDR, was abolished. Even 30 years after the “transition,” the availability of and participation in sports clubs and sports communities in eastern Germany are significantly lower than in the so-called former West German federal states. In 1988, the German East was on the verge of becoming the strongest sports power in the entire universe, and is now the least athletic part of Germany.

Well, objections are to be anticipated — it was only doping, after all, that gave the GDR its sporting successes (and not a widespread sporting movement and development that eclipses anything we have seen since). But it is true, that it would be childish to let sport alone be the criterion if we want to address the question of whether the GDR was the better Germany.

So is the answer to this question perhaps not so easy after all? The GDR did not only outshine the Federal Republic in competitive sports. It also banned the beating of children in school, whereas in Germany’s post-war democracy, students were still allowed to be beaten for 30 years. In the ten years prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, one million more children were born in East Germany than in the ten years after. In 1990, the East was the youngest part of Germany. And afterwards, at breakneck speed, it became the oldest part. Mental illness among schoolchildren has quadrupled since the fall of communism. Apparently, we have gone from a healthy society to a sick one. So was the GDR the better Germany?

A few weeks ago, the Bundestag decided that, starting in 2026, all children in Germany should have the right to free after-school care until they start 5th grade. What none of the parties had mentioned in this context was that all GDR children had this right until 1990. A few days ago, an institute at Leipzig University published a research result that was surprising even for the scientists themselves: the probability of becoming a victim of neglect, violence or abuse was significantly higher in the democratic Federal Republic than in the dictatorial GDR. But was the GDR therefore the better Germany?

In 1990, more than 90 percent of women in the GDR between the ages of 25 and 60 had vocational training, completed a course of study at a technical college or graduated from a university. At that time, this was true of no more than 35 percent of women in the FRG. The professions of judge and teacher were women’s professions in the GDR. Equal rights for women in marriage were established for GDR women from the very beginning, as was their self-determination over their own occupation and the power to dispose of their income. West German women still had to wait decades for all this. So was the GDR the better Germany?

Among the greatest crimes of the 20th century were the wars of the French and the Americans in Indochina/Vietnam. In the process, 3.5 million civilians lost their lives, including half a million Vietnamese children. The GDR was on the side of these children, the Federal Republic was on the side of their murderers. So was the GDR in truth the better Germany?

The army of the GDR, the National People’s Army, was the only German army since Charlemagne that did not start a war. The United Nations ranked the GDR among the ten lowest crime states on earth. The probability of losing one’s life through murder or manslaughter was twice to three times higher in the democratic Federal Republic than in the dictatorial GDR. Again the question: Was the GDR the better Germany?

The GDR had enshrined a right to work and thus full employment as an individual right of its citizens. It had — in contrast to today’s situation — a comprehensive labor code and about 5000 children’s holiday camps for the children of employees. Almost all of these camps were dissolved in the two years after the fall of the Wall. So was the GDR the better Germany after all?

The last party to take care of the construction of new social housing in my hometown of Potsdam was the SED, i.e. the state party of the GDR. In the year of the collapse, i.e. 1989, almost 1000 new and affordable apartments were handed over to their tenants in this city. Since then, new apartments have been built not for ordinary people, but for rich people. Nowhere in the new German states has this actually been different. Is it necessary to call the GDR the better Germany for this reason?

Today, there are 600 lawyers working in Potsdam alone, which is more than 100 more than were admitted to the bar in the entire GDR. So life in the GDR got along practically without this ultimately unproductive huge mass of lawyers that we have to feed today. Comprehensibility even for the layman characterized their legislation. Arbitration commissions and lower-level social committees did their part to decriminalize conflicts in GDR life. Given this background, was the GDR perhaps the better Germany?

The GDR had provided all full-time students with a stipend that allowed them to cover such basic needs as housing, food, travel home, and even going to the movies and pubs. It even ended up granting 11th and 12th grade students a monthly sum equivalent to apprentice pay. Medication co-payments were unheard of, and eyeglasses could be made at Social Security’s expense. Does this provide answers to the question of whether the GDR was the better Germany?

In the GDR, an unfettered relationship to the human body developed; even the distinction between nudist and textile beaches disappeared in the end, because everyone could do what they wanted in this regard everywhere. After the GDR, a society in which prudery and pornography go through life arm in arm became widespread in East Germany. Was the GDR the better Germany from this point of view as well?

There will be different answers to this important question. The teacher who was a civil servant 25 years ago probably sees things differently than the academic scientist who was laid off after 1990 and never found employment again. Because one can list completely different examples and draw up a completely different balance sheet, I leave it up to everyone to find his or her own personal answer. However, I will give one essential answer: The GDR was first and foremost the other Germany. It was the Other. And that is what makes it so special and the hatred of it so convincing.

The German Empire, the Weimar Republic, the Nazi dictatorship and the Adenauer state — what did they have in common? The crucial thing. They were all variants of bourgeois rule, they were — one as much as the other — capitalist monetary rule. And the social structure remained the same even during the transitions — with minor partial shifts. The traditional and vested power elites (moneyed aristocracy, nobility, churches, civil service, judicial caste, foreign office, officer corps) always persisted, always floated on top and renewed themselves out of themselves. This was the case during the transition from the Empire to the Republic (with a few exceptions for the nobility). The privileges of the aforementioned elite castes were all confirmed by Adolf Hitler (if they were not Jews) and if they were willing to move together a little to let the new Nazi oligarchy join them at the cribs. Thus “purified”, the West German post-war democracy took over these elites: Hitler’s generals became Adenauer’s generals, Hitler’s diplomats became Adenauer’s diplomats, Hitler’s judges became Adenauer’s judges, Hitler’s state secretaries became Adenauer’s state secretaries, Hitler’s teachers and university professors became Adenauer’s teachers and university professors. And the bishops of both major denominations also remained what they were, despite all their dismaying closeness to the Nazi state.

And the GDR did not provide this image. That is what makes it so unique. On its territory, the traditional, bloodstained and guilt-ridden German power elites, who were twice such a terrible calamity for Germany, Europe and the world in the 20th century, had nothing to say for 45 years — apart from the churches, which undoubtedly also existed in the GDR. (They continued to exist as corporate bodies and also had influence, but they did not have a determining influence on the government there). This exclusion from power, which the traditional elites had to put up with on a third of the German territory and that for almost half a century, is the actual fall from grace of this state. Hence today’s reckoning by a reappraisal industry laced with millions. That is why the hatred for the GDR is so genuine and so

fundamental. And so endless.